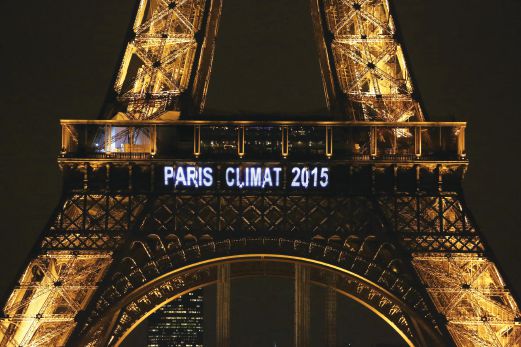

Last Saturday, the Paris agreement on climate change was struck and hailed as a historic turning point towards averting a climate catastrophe. Along with the adoption of Sustainable Development Goals, conclusion of Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement negotiations and establishment of the Asean Community, we approach the end of 2015 as a landmark year for global and regional partnerships.

As international cooperation blooms, optimism for translating this spirit towards a more united world is tempered by recent events and trends. The continued threats of extremism, polarising debates on immigration and increasingly divisive rhetoric in various parts of the world threaten to shape another future reality.

The Paris United Nations Climate Conference, or COP21, demonstrated both ends of this reality. On one end, successfully bringing together 20,000 people from 195 countries with different priorities, circumstances and capabilities was no mean feat. Yvo De Boer, the former executive secretary of the UN Convention on Climate Change, likened this to playing chess on 15 different chessboards at the same time.

On the other end, a huge trust deficit between developed and developing countries risked undermining the whole negotiation. Two issues in particular served to make or break the negotiations.

Firstly was addressing the issue on differentiation — the level of responsibility. Developing countries accused developed ones of being unwilling to bear a fair share of the responsibility, with the US$100 billion (RM436 billion) a year promised by developed countries towards a green climate fund being slow to arrive. Developed countries asserted that any agreement must be applicable to all, including developing countries. Secondly was historical responsibility, where developing countries insisted that rich nations take on extra burdens to make up for the decades of polluting energy as the basis of their economies.

Now that countries have come to a consensus, how effective will the agreement be in catalysing collective action?

Cynics will say it is insufficient. Scientists have warned that global warming must be limited to well below 2ºC to avoid dangerous climate change. Yet, Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, the commitments towards climate action of each country, will only be able to limit the warming to 2.7ºC. Furthermore, the term “legally binding” does not apply to achieving the targets themselves, but rather, is limited towards submitting those targets and subjected to periodic reviews to show that countries are making progress towards them. This puts the onus on national governments to fulfil these commitments.

Optimists point to previous successes, such as the Montreal Protocol, where an international agreement led to a successful global effort to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of substances responsible for ozone depletion.

A more realist perspective suggests that it will merely be a starting point for a process towards closer cooperation. Climate change is a much more complex problem than ozone depletion. Being considered a “problem without a passport”, national borders are inconsequential, with emissions from one side of the world having the same impact as emissions from your own city.

This is the crux of the challenge. Climate change risks being the ultimate case of the tragedy of the commons, where there is not enough motivation for individuals to alter behaviours, despite the devastating collective damage.

Politicians are likely to see the impact of any measures implemented only after their terms in office. Industries do not want to risk losing a competitive edge through increased costs for clean energy. The motivation for individuals is often confined to knowing that it is the “right thing to do”.

But beyond the moral imperative, even acting purely on self-interest provides a clear rationale for climate action. The devastating floods in Malaysia at the end of last year, which resulted in at least 23 deaths and damage to public infrastructure amounting to RM2.9 billion, were partly blamed on climate change. Despite investing more than RM9.3 billion on flood mitigation from 2004 to last year, the costs and impacts will only rise if global efforts end in failure.

A better understanding of the notion that we live in an interdependent world goes a long way in providing the impetus to take action. Education can play a large part in inspiring cooperative commitment. This notion is enshrined in the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025, with an aspiration that students “will be global citizens with a strong Malaysian identity, ready and willing to contribute to the harmony and betterment of the family, society, nation and global community”.

The need to “think global, act local” is not confined to addressing climate change. As the world becomes smaller through technology and international agreements, navigating an increasingly interconnected world will be critical to move towards a more secure future. The Paris agreement serves both as an accomplishment and a test towards closer cooperation in solving global challenges.

This article first appeared in The New Straits Times on 15 December 2015