After the colour and drama of another Philippine election, what kind of country will a controversial President Duterte and his new government turn out?

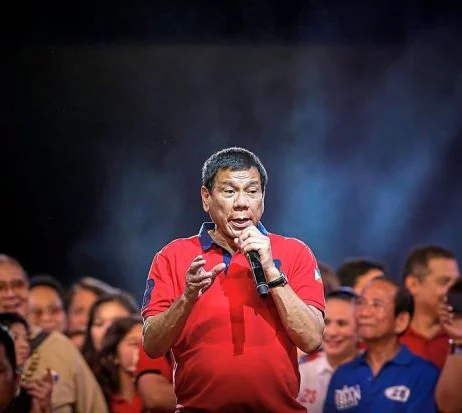

FROM almost nowhere, a dark horse candidate sweeps past his fancied political rivals to surge towards the coveted national leadership. Loud, brash, crude, insensitive but irrepressibly popular, his unorthodox manner and disturbing pledges threaten as much as excite. Clearly, he has touched enough raw nerves to ensure constant media focus on him and his campaign.

Defying simple and standard labelling, allegations of financial impropriety, including tax evasion, fail to faze the defiant and abrasive candidate who continues to accumulate grassroots, anti-establishment support.

The apparent success of his campaign is a test of both his political acumen and the democratic system that had enabled it. Thailand had that moment with Thaksin Shinawatra, and the US is undergoing it with Donald Trump. One week ago the Philippines embarked on that path by electing Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte as President.

Exactly what kind of government will such a personality make? Is his bite really as bad as his bark, and is that as bad as others have said it to be? The answers are still imprecise as the political character of the new president himself continues to evolve, not least in relation to the realities of the day. There has been no shortage of warnings and alarm over Duterte’s pronouncements, or casual comments, on due legal process and democratic accountability.

Along with many others, outgoing President Benigno Aquino III has sounded those warnings. But since Duterte’s detractors include his political opponents, the warnings lack the credibility they need.

How has a once-unfancied candidate turned voters around so much while defying virtually all conventions? Such “mysteries” will remain unresolved and unresolvable as long as the political establishment itself refuses to take stock of the underlying realities.

Duterte’s popular appeal to get tough on crime and criminals resonated with the people. If previous presidents had been as convincing in the task, or his rivals as persuasive in promising to do it better, his candidacy might have been in the balance.

Another important aspect of Duterte’s popularity is his direct and unabashed style. His loudness and unpolished manner only helped to authenticate the apparent honesty of his content and delivery.

In contrast, the middle-class special interests that his rivals had become identified with were a disabling liability. So when Duterte championed the poor, in a society where the poor still needed championing, he came away with greater credibility than the other aspirants.

Yet another edge that he held over his rivals as a candidate was that he was an outsider. As with Trump and Thaksin, that made his attacks on a gridlocked establishment weighed down by sleaze more plausible. In time he may develop his own brand of sleaze, especially after he concentrates power at the expense of independent critiques and accounting, but voters have decided to leave that for another day.

On polling day itself, Duterte could still have been stopped if his two closest rivals, Mar Roxas and Grace Poe, had joined forces. Aquino had said as much in a last-ditch effort to derail Duterte’s campaign. Opinion polls had placed Duterte some 10 percentage points ahead of Roxas, and slightly more in front of Poe. With their popularity combined in a joint campaign, they could have defeated Duterte by up to 10 percentage points instead.

Philippine election campaigns are typically rich in the personal character of the candidates, with little difference in ideologies. They also bear a trademark personal scramble for votes at the expense of virtually everything else.

Among the allegations against Duterte during the campaign was his alleged link to “Joma” (Jose Maria) Sison, the former university professor and head of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

That could have worked to cut the appeal of his pro-poor message, or so his rivals seemed to have hoped. But again, the allegation failed to work.

So an almost “teflon” Duterte continued to campaign effectively and won. Once more, his defeated rivals need to reflect on how they had also been culpable in neglecting the plight of the poor.

Now that Duterte’s victory has become a fait accompli for the rest of the country, critics and opponents alike are resigned to pondering his, and also their, next moves.

There is a universal assumption that however radical a candidate may be, as incumbent he tends to mellow. Already Duterte and his team have encouraged this thought. Soon upon becoming the “Presumptive President,” Duterte indicated that he would model his Cabinet after the politically correct line-up of arch-liberal and conservative target Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada.

Trudeau’s Cabinet is described as gender-sensitive and ethnically diverse, the supposed antithesis of Duterte’s rough and chauvinistic image. The mellowing of Duterte had begun.

And what of the hardened criminals for whom Duterte was supposed to be the worst nightmare? The president-elect would now consider building maximum security prisons for them as in the US. It is a far cry from the random mass murder of suspects and convicts he is said to have promised, or threatened. More mellowing can be expected on other fronts, along with protrayals of Duterte as a flip-flopper.

The market seems to have picked up on signs of a maturing Duterte presidency to be. Confidence is returning to the incoming political leadership after a brief period of doubt, as the peso remains strong. Besides, how could any business community be averse to promises of heavier doses of law and order? Businesses would be ecstatic if a leader could make good on pledges to make the proverbial “trains run on time.”

On his part, Duterte is smart enough to understand that the national economy is the make-or-break factor for any leadership. Brazil, among others, is a showcase of how economic fortunes can determine the fate of leaders regardless of anything else. However, Duterte and all that he represents is still untested on foreign relations. He has so far issued conflicting signals on how he would deal with an assertive China on disputed territory in the South China Sea. For the Philippines, the issue concerns more than China as it also involves the US and Manila’s security treaty with Washington.

Adding weight to the matter is a Duterte presidency’s inheritance of the legal tussle that the country has brought on with China. Dealing effectively and satisfactorily with the issue demands a degree of perspicacity, nuance and sensitivity that has seemed elusive to Rody. But stumbling over it can also spell disaster for the new government. It cannot be an issue that Duterte’s government would want out of choice, as an additional burden to having to tackle various domestic challenges at the same time. Yet it is something that no government in Manila’s position can avoid addressing.

This, and how the Philippines will now position itself on the claim to Sabah territory among descendants of the erstwhile Sulu sultanate, will test Duterte’s statesmanship to the hilt. It can be assured that such matters will be watched closely by much of the rest of the world.

Article by Bunn Nagara which appeared in The Star, May 15, 2016.