Most countries in the world have adopted some form of progressive taxation, following the conventional wisdom that “the rich should be taxed more than the poor”.

Ironically, despite progressive taxation, experts agree that the global economy suffers from deepening income inequality. This trend was highlighted last year by the World Economic Forum in Davos. Reforms are clearly needed. But how?

Poverty today is defined by more than just a lack of income. It is rightly considered to have many dimensions — social, administrative, psychological and political. The poor have restricted access not only to social services but also democratic participation. Politicians and free market economists, however, continue to offer simplified “silver bullet” solutions to solve poverty and inequality.

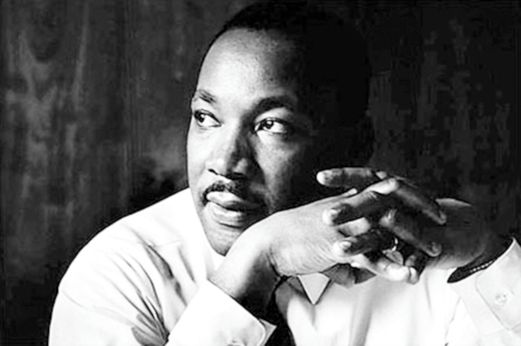

Back in 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr asserted that the most effective yet simplest approach to abolishing poverty directly is through guaranteed income, regardless of whether recipients work or loaf around.

In recent years, libertarian-minded William Easterly championed the idea of cash transfer to the poor.

“Stop wasting our time with summits and schemes,” he said.

“The aim should be to make individuals better off, not to transform governments or societies.”

Six years ago, The Economist reported that a charity in London had conducted a cash-transfer experiment involving 13 homeless people.

They were each given £3,000 and free to spend on anything unconditionally.

The results were empowering; after a year, 11 of them had a roof above their heads, were enrolled in educational institutions and had made plans for the future.

Free market reformers, led by the late Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, however, have come up with a slightly different proposal — negative income tax (NIT).

The basic idea of NIT is to tax people who earn more than the income tax threshold and provide financial assistance for people below the threshold, hence the name negative tax.

In rich countries, the NIT debate has been increasingly prevalent in recent years due to the lagging trend of wage growth compared with labour productivity.

People work longer hours, produce more output and yet are paid the same wages.

The concern regarding NIT is the disincentive to work. To minimise this disincentive, Friedman said NIT should be progressive too.

Let’s say NIT is 50 per cent, and the income threshold is RM10,000. If the family earns nothing, they will receive RM5,000 (50 per cent of the threshold). If their earnings increase to RM2,000 (or RM8,000 short of the threshold), they will get RM4,000 from NIT — a total after-tax income of RM6,000. If pre-tax income is RM3,000, they will get RM3,500 from NIT, making a total of RM6,500.

It is argued that no stigmatisation is attached to NIT, no costly administration of social safety programmes, and no minimum wage is needed. It magically cures inequality, too.

Without NIT, there is a RM2,000 gap between no-income earners and those who earn RM2,000. With NIT, the former takes home RM5,000 whilst the latter gets RM6,000, a difference of RM1,000.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld carried out NIT experiments.

It was shown that poverty and spending on many social services were reduced.

It also show-ed insignificant reduction in hours work-ed, particularly among second-income parents. There was no evidence of the main breadwinner exiting the labour market.

Yet, one must be wary of the underlying assumption of perfect information.

In economics, it means that people know exactly what to spend their money on, what to consume and at what level.

If the assumption does not hold, the government risks unintended consequences.

The distortion might be minor in small-scale experiments; but in large-scale experiments, the risks would be greater.

Firstly, the notion of guaranteed income will pressure the government to equalise NIT payments for no-income earners with the existing minimum wage.

This implies that the government will continue to subsidise the citizens beyond the minimum wage. Like other social security benefits, there will be pressure to revise NIT every one or two years, thus magnifying the fiscal burden.

Secondly, if the government decides to abolish the minimum wage, NIT is still tricky.

Guaranteed income by the government eliminates the responsibility of corporations to pay their workers minimum wage.

Thirdly, abandoning meticulous applicant-by-applicant examination, NIT creates a space for moral hazard.

The size of the informal economy in emerging economies over the last decade (65 per cent in East and Southeast Asia, 82 per cent in South Asia) means that much of the income goes underreported.

NIT may thus, incentivise formal-sector employees to shift to informal employment, causing a loss in tax revenue.

One cannot let good intentions justify potentially disastrous consequences. There is no magic silver bullet for a complex problem like poverty.

The government needs to take gradual steps such as collecting information, improving transparency and consolidating existing social security programmes.

This article first appeared in New Straits Times on 24 May 2016.