Malaysia regards public examination results as important determinants of a students’s progress to higher education, as well as occupational opportunities.

THERE are Malaysians who are dissatisfied with the education system and are looking for

approaches beyond the top-down classroom model.

The Malaysian education system should undergo a paradigm shift in the teaching and learning

process to prepare the younger generation for the 2050 National Transformation Programme.

What and how we teach our children today will determine the attitude, values, social awareness as

well as skills of tomorrow’s citizens. Perhaps, it is the right time to rethink the goal of education.

Is it to socialise young people so they can fit into the fabric of society? Is it to train a workforce for

business and industries? Is it to introduce young people to greater possibilities that life has to offer?

These are all reasonable goals, but they do not really address the deepest purpose that education

has — helping young people to be creative, bringing new ideas and creating their own future.

In this age of globalisation and information technology, there is always a limit to how much educators

and teachers can convey to their students.

Any knowledge disseminated now stands a good chance of becoming outdated as soon as students

step out of school.

However, if students are equipped with critical-thinking and learning skills, there is no limit to what

they can learn.

As Thomas Friedman proposed in his book, Thank You for Being Late, one of the things students

need to learn at school is how to construct frameworks for seeing the world and how they work.

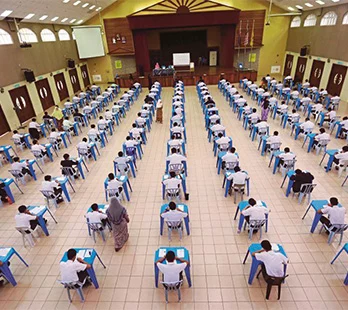

Like most Asian countries, Malaysia regards public examination results as important determinants of

a student’s progress to higher education, as well as occupational opportunities.

The primary function of schooling is seen as a way for entry into privileged jobs.

As a result, the emphasis by students, teachers and parents is on performing well in examinations,

which are considered the only way for academic attainment.

Other effective characteristics, such as values and attitudes — .important elements in the

development of a well-rounded individual — .are deemed irrelevant.

In the Asia Public Policy Forum on “Improving Education Access and Quality in Asia”, Harvard

Professor Lant Pritchett, citing recent research on literacy among Indonesian students, found their

level to be similar to that of junior high-school dropouts in Denmark.

He said he feared the same could be true with Malaysia if its schools failed to prepare students for

university education.

At the same time, there is no deep understanding of the materials. Instead, it is rote memorisation,

application of theory and regurgitating it in exams.

He said the state of education in the country is not the fault of individual teachers. It is not that they

are not smart or capable or diligent in doing their job.

The problem is the system they are a part of. If we want to change the system, you have got to

change the rules and practices.

As most indicators suggest, there are many issues of survival that we need to respond to by changing

the system and changing the way we conduct our daily life.

If we are to develop healthy social processes and create a preferable future, we need to reform our

education system, which is more effective, appropriate, equitable and flexible.

We should not feel shy in addressing current challenges and limitations of our education system and

institutions.

Doing what is already being done a little better falls far short of what will be needed.

The needs of the world urgently require that some country take a lead in starting the process of

transformational change.

Why should Malaysia not be the first?

Article by Dr Abdul Wahed Jalal which appeared in New Straits Times, May 2, 2017.