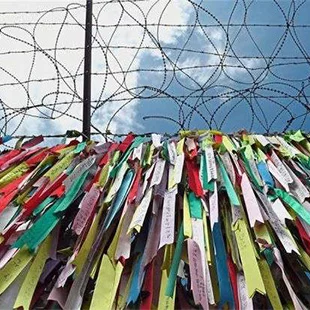

Call for peace: Ribbons with inscriptions calling for peace and reunification being displayed on a military fence at Imjingak peace park near the Demilitarized Zone. — AFP

As both tension and speculation mount on the Korean peninsula, emotions run high while sober

minds and rational solutions are hard to find. THE great leader strides up to the stage amid applause, people clap, he claps in return, everybody is clapping happily.

Tension and controversy abound, but worry and concern are in another world in this wonderful joyous

moment. The great leader is pleased, his great ego is pleased, and everyone else is out to please.

Is this another launch of a campaign or a missile in Pyongyang? Or another policy or executive

appointment in Washington?

Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump, representing supposedly different ends of any spectrum, have quite

different attributes – and share some interesting ones.

Kim, like his father and grandfather, has been anxious for US recognition as leader of a legitimate country

following the 1953 partition of Korea. That, and to keep his country safe from attack – chiefly from the US.

A century ago, Japan invaded Korea then Tokyo became a US ally after its defeat in WWII. In the Korean

peninsula’s troubled history, the US has been with the South, aiming barbed rhetoric against the

communist North.

US forces have been stationed in Japan and South Korea for decades. In Pyongyang’s view why would

the US, as world supplier of “regime change”, not want to replace its leadership with an ally or crony?

For the Kims, ensuring the second aim of national security involves acquiring nuclear weapons as

deterrent against foreign attack. But that militates against the first aim of getting US recognition.

Successive US presidents have ignored or dismissed Pyongyang’s quest for direct talks. Then incoming

President Trump said he was prepared to have talks with Kim – but some US officials were perturbed.

For months, the Washington Beltway hounded Trump for supposedly being too cosy with Russian

President Putin.

It was a long-term test of his testosterone and adrenaline levels. In that time, Kim was happily testing missiles and telling the world about the ones that did not quite fail. He had his testosterone and adrenaline levels to maintain too.

As things came to a head, Trump lambasted Kim for using the US as a target yardstick for the supposed

potency of his intercontinental ballistic missiles. The lack of transparency in Pyongyang meant that

routine rhetoric and hype often substituted as news.

After Putin, Trump could not be seen at home as being too friendly to another “edgy” foreign leader.

Besides, he needed to revise earlier remarks questioning continued defence support for South Korea and

Japan, countries most threatened by the North. In a fit of fancy between tests, Kim last weekend boasted that his missiles could now hit the US mainland from Los Angeles to Chicago. Some officials said Guam, and others cited Alaska at most.

In similar emotional mode Trump vowed to rain “fire and fury” on North Korea (DPRK) if Kim dared try it.

The US has many more warheads on the mainland as well as other forces in Japan, South Korea and

Guam. Guam is a DPRK target benchmark because it is a vital US military hub – at least three known bases

house thousands of regular troops, Special Forces personnel, stealth bombers and nuclear submarines,

among others.

In any conflict against US assets, Guam would be a considerable prize. However, DPRK missiles are still

not capable of reaching Guam even if deployed for offensive purposes. Some have said they might hit Alaska, which is not nearer than Guam from DPRK. Kim’s missiles are still incapable of landing on US soil.

In the midst of heated rhetoric and exaggerated claims, it is especially important to be realistic about

actual possibilities and prospects.

During the week Pyongyang announced the notion of striking Japan and Guam with four Hwasong-12

intermediate-range missiles. But a missile’s range capability and credible strike potential are different

things.

That announcement provoked Japan to declare three days ago that it could thwart any such strikes. This

was contradicted by experts at the US-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins University.

Still, among several specialists there is no sense of undue alarm at Pyongyang’s actual capabilities.

Although anti-ballistic missile capacities are still limited, DPRK capabilities are worse in being

handicapped.

Officially, DPRK missile tests have had a 31% failure rate in the past three years. Unofficially the figure is

higher because several failed tests are unannounced and not supposed to be known.

Japan, South Korea and the US are all armed with anti-ballistic missile systems that are as advanced as

anywhere in the world and likely better than others. These include the THAAD, Patriot and Aegis systems

launched from land and sea.

A preoccupation with DPRK missile strikes does not help in understanding other threats that are more

real. Despite provocative tests and reckless statements, Pyongyang has done nothing for others to doubt

its posture is still defensive.

Among the specialists who are not on board the “Kim attacking Guam” bandwagon is Prof Richard Bush.

He suggests greater dangers in misreading Kim and taking the bandwagon route, missing opportunities

for a way out.

Japanese and South Korean experts see risks to ruptures in their countries’ security alliances with the

US. An obsession with Pyongyang’s missiles can be distracting and misleading.

At the same time, playing up Kim’s threat is actually helping him by building up his stature and his

domestic renown. It also confers a greater threat potential on him than he can achieve on his own.

It would be playing his game and declaring him the winner. It is nothing less than what he wants and

needs.

Jonathan Pollack sees another danger in Pyongyang selling nuclear weapons technology to terrorist or

criminal gangs. That can pose more dangers than simply having to face one rogue nuclear state.

Jeffrey Bader warns against the simplistic option of a US first strike against DPRK nuclear sites. It will not

work because not all sites are known, while retaliatory strikes against Japan and South Korea are virtually

guaranteed and excessively costly.

Since open nuclear warfare would be suicidal, the only realistic option is negotiations. But many have

already misread Kim as someone not amenable to talks.

Even as tension builds, Trump is still the most amenable leader for Kim if he is not too hidebound to

understand and appreciate it. Trump has no anti-Pyongyang baggage and has said he is prepared to

meet Kim.

This also happens to be the best time for the US and China to forge a new partnership with respect to

DPRK. The two main stumbling blocks to closer China-DPRK relations are Xi and Kim.

Kim the young man is not like his father and grandfather before, ruthless as they also were. Neither is Xi

like previous Chinese leaders averse to offending a ruling Kim.

That means the situation enables and encourages closer working relations between Washington and

Beijing. Trump and Xi both know they need such a breakthrough.

Yet, despite the good prospects for peace, the chances of conflict are also high. Indecision and conflicting

statements in Washington may telegraph to Kim a sense of administration weakness and disarray.

Meanwhile, Japan appears hamstrung, South Korea looks constrained and China lacks options. It is not

the best way to impress Kim with the strength and prowess that can be aimed at him.

Article by Bunn Nagara which appeared in Sunday Star, 13 August 2017.