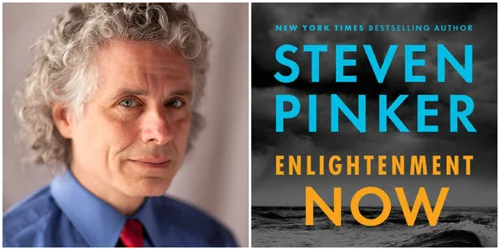

WHEN BBC’s Stephen Sackur interviewed American cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker on Hardtalk three nights ago, the discussion might have appeared dry and dull.

That perception would be a mistake. The interview covered not only Pinker’s new book celebrating Enlightenment values and human progress, but also current issues around the world. Prof Pinker’s previous books, like his assertions on science and social advancement, have been controversial for different reasons. So is his latest book Enlightenment Now.

However, his observations on the current state of society are less disputed. The policy contradictions of the Trump administration, for example, are seen to result from the irrational basis of populism among the populace.

Pinker also said despite the US being portrayed as a leading Western democracy – with Enlightenment ideas such as political and individual liberty, human rights, scientific reason and secularism enshrined in its Constitution – it is a “laggard” compared to countries in Europe. The US is “an ambivalent Enlightenment country” because it is a deeply divided nation. That is all too obvious now, with the Trump administration going one way and the Establishment including the mainstream media going another. So the world’s leading economy is also “a peculiar example of a Western democracy.”

US foreign policy reveals even more contradictions, such as toppling unfriendly dictators in some countries and propping up friendly ones in others, while claiming anti-dictatorship as justification. Or is that only rational policymaking in the perceived national interest – plus rationalisation? Much of this policy behaviour however has been consistent, being common to Democratic and Republican administrations through the years. Rationally, only so much can be blamed on “Trumpism”.

The dualism and the ambivalence have been more pronounced in some past administrations. George W. Bush gained notoriety by, among other things, declaring that other countries were either “with us or against us.”

That was never the most persuasive way to recruit allies for the US invasion of Iraq. Nor was it the most enlightened or rational.

Such irrationality returned with US Ambassador Nikki Haley’s defiance against other countries’ refusal to back the US decision to shift its embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Her threatening tone confirmed the irrationality – along with the futility and unenlightened quality of the decision. Meanwhile, US domestic politics continues to conform to Pinker’s “laggard” assessment. The country continues to devour itself as the Establishment persists in hounding the elected presidency for any and every reason, or sometimes even none at all.

Trump watchers, fans and critics alike may want to note that – regardless of their political views – a benchmark date was Dec 18, 2017. This was when the administration rolled out its first, much awaited National Security Strategy, delivered by Trump himself.

The attacks on the document within the US started immediately. Some found it to be interventionist abroad and thus it was duly criticised for being untypically Trump.

Doubts were expressed about its actual realisation because of this contradiction. There were also questions about how much of Trumpism it actually contained. Still others mourned the return of “great power military conflict” in the way it portrayed the US as being under siege by foreign rivals. Some said Trump himself had ignored its key elements, and others said the document itself should be ignored (Foreign Policy journal).

A New York Times commentary called it “a farce.” Several (Foreign Affairs journal and others) called it “delusional”.

Few saw it as anything else, such as characteristically blunt, revealing, unoriginal in basic outlook – and thereby a familiar hand-me-down from past presidencies. Much of that could have been foreseen in a careful analysis of US policy abroad in the preceding months.

In October, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic announced that he wanted his country to join the EU while maintaining close ties with fellow-Slavic Russia. In short, he wanted Serbia to be a non-aligned country in Europe.

As a Western country, seeking to join the EU and wanting to keep close relations with Russia would each be a task in itself. Hoping to do both at the same time appears to require something extraordinary.

But perhaps these are extraordinary times – after Britain’s Brexit referendum and doubts about other EU countries remaining, Brussels should be keen for more countries to join. At the same time, the US Establishment at least should be happy to see a Russia-proximate country in the EU, for the strategic and intelligence input that the West may gain from it. Or that was what Vucic might have thought.

Within days, US State Department official Hoyt Brian Yee piled pressure on Serbia, insisting that it had to choose between Russia and the West. The “with us or against us” mentality rides again. Contrary to Vucic’s hopes, the US Establishment sees a Russia-proximate Serbia becoming an EU member as a loss and a prospective drain in strategic and intelligence terms instead.

At issue also is the Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center in the Serbian city of Nis. It is equipped for search and rescue operations but may also house military and intelligence-gathering equipment. Serbia swiftly slammed Yee’s pressure. For its part the EU, being less ideological than the US Establishment, said Serbia had to normalise relations with Kosovo before being considered for EU membership.

EU members Bulgaria, Greece and Romania have pledged support for Serbia’s membership bid. But a tug-of-war between the US and Russia has already begun over Serbia.

In late October, Russia gave Serbia six MiG-29 fighter jets as part of an arms package. Still to come are 30 tanks and as many armoured vehicles.

The following month Serbia held a four-day military exercise with US forces near Belgrade. Serbia, Russia’s only friend in the former Eastern Europe, is already a member of Nato’s Partnership for Peace programme.

Russia would be horrified if Serbia ever joined Nato. In December Moscow laid plans to supply Serbia with military helicopters, missile systems and more MiG-29s. Russia is not known to have pressured Serbia to choose one side or the other – only to give the Nis base enhanced status. Last Wednesday Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov criticised the Western attitude of pressuring other countries to choose sides.

The essential dualism of either-or, us-or-them has been associated with the Manichaean tendency that shapes and colours much of Western culture and political discourse. It may not come as naturally to Russia’s Eurasian outlook.

The Indian scholar Kashish Parpiani recently noted this Western characteristic in US perceptions of India and China. One is a democracy and automatically deemed worthy of Western support, while the other is communist and must therefore be regarded as a rival.

He traced this dualism to 1959 in the speech of then-Senator John F Kennedy. With the latest US National Security Strategy, it has evidently survived the years and the changes of administration. Far from being just a philosophical oddity only of academic interest, a divisive dualism is dangerous for any country in Europe or Asia – or anywhere else. No country likes to be forced to choose sides. Regardless of the eventual fate of the Trump-Xi relationship, the US Establishment has decided that China, like Russia, is to be designated an opponent. The National Security Strategy has set the stage for intercontinental conflict.

If Trump’s alleged isolationism is bad, such aggressive interventionism – familiar as it is – is much worse. Having both at once is another contradiction.