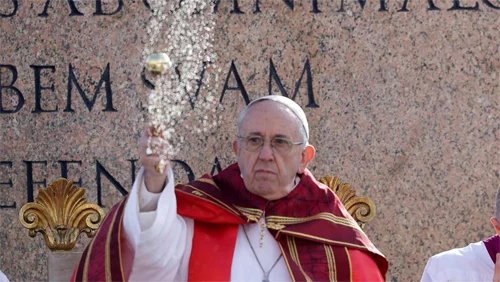

With religious apathy on the rise in Europe, current and future generations might fail to appreciate their heritage and a common language of cultural markers that can no longer be taken for granted.

It’s official. Europe is becoming a godless continent. According to a new report published by St Mary’s University in London, in 12 out of 22 countries surveyed, more than half of young adults "claim not to identify with any particular religion or denomination”. The Europe’s Young Adults and Religion survey paints a picture of a stark decline in faith. It says that the proportion of young adults aged between 16 and 29 with no religious affiliation at all is as high as 91 per cent in the Czech Republic, 80 per cent in Estonia and 75 per cent in Sweden.

A mere 7 per cent of young Britons now identify as Anglicans, which is grim news for England’s nearly 500-year-old established church while in France only 2 per cent identify as Protestants. The trends are not uniform. In Poland, Lithuania and Slovenia, support for Catholicism is still strong with 82, 71 and 55 per cent respectively of young people remaining adherents. However, weekly attendance of mass – which was quite unthinkable to miss when I was growing up – has dropped precipitously among this age group, with only 2 per cent of Catholics in Belgium, 3 per cent in Hungary and Austria and 6 in Germany saying that they went to church every Sunday.

“Christianity as a default, as a norm, is gone and probably gone for good – or at least for the next 100 years,” the report’s author, professor Stephen Bullivant, told The Guardian.

This is shocking news for a variety of reasons. I have written here before of how the decline of Christianity in Europe runs the risk of current and future generations failing to understand their history and their heritage and a common language of cultural markers that can no longer be taken for granted. Were he alive today, for instance, that icon of the British left, Tony Benn, would surely be encouraged by his publishers to change the title of his memoir Dare to Be a Daniel, on the grounds that younger readers could not be presumed to pick up on the biblical reference.

It also makes genuine understanding between Europe and the rest of the world harder to attain. For while Europeans increasingly tend to be part of the roughly 16 per cent of the global population that is religiously unaffiliated, according to the Pew Research Centre, they are vastly outnumbered by the 84 per cent who do adhere to various religions – with Christians currently the largest group at 31 per cent, Muslims second at 24 per cent and Hindus third at 15 per cent. Broadly speaking, people of faith might disagree with each other – indeed, members of different religions are bound to think each other are wrong in important aspects of their beliefs – but they are nonetheless united by the conviction that there is a higher power responsible for creation and to whom we will all have to answer.

To many of them, atheism is not just a different belief system; it is something utterly alien. Reporting on an interfaith medical project in Kenya a few years ago, I asked a local aid worker about the numbers of Muslims, Catholics, Pentecostalists and Anglicans in the country. She was happy to answer. When I asked her how many atheists there were in Kenya, however, she looked at me as if I had lost my mind.

The fact that the difference in world view between atheists and the religious is qualitatively more significant than that between those of different faiths is undeniable. But there is another problem.

In most parts of the world, religion is the bedrock of society and closely informs the legal system, commonly accepted moral norms and broader ideas and aspirations about rights. While they all can be debated, certain parameters are fixed because the foundations are firm – a belief in God. It is not wrong to steal because man says so but because it has been divinely decreed.

Thus the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam ends with the lines: “All the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic Sharia. The Islamic Sharia is the only source of reference for the explanation or clarification of any of the articles of this Declaration.”

Removing the bedrock of religion, on the other hand, leaves a moral vacuum. As the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky famously wrote: “Without God, everything is permitted”. Law and morality are then based on what the majority of people think they ought to be at any given time. They become mutable, contingent, because there can be no timeless principles.

There are many who would argue that it is no coincidence that Stalinism, Nazism and the murderous Maoism of Pol Pot were all atheistic creeds.

This is not to say that there are not many perfectly reasonable and decent atheists who live lives of conscientiousness and compassion. But conscience freed of the moorings of faith can drift to dark places. So a godless Europe would represent an innovation and an uncertain one at that.

There was another recent survey worth mentioning in this context. It showed that Muslims in the UK were more likely – by more than 10 per cent - to say that their British identity was important to them than were the general population.

With irresponsible populists across the continent warning ludicrously of the dangers of “Islamisation”, perhaps they should reconsider. Those that they wish to marginalise might be the most loyal Europeans of all. Their faith and their religious adherence remain strong. Could it be European Muslims who end up saving the continent from the emptiness and unanchored morality of atheism?