Article by Dato’ Steven Wong which appeared in New Straits Times, 29 May 2018

IF there is only one thing that we know about ourselves as humans, it is that we are mentally hardwired to hear what we want to hear. The saying that “opposites attract” is a nice sentiment, but, scientists have consistently found this to be a myth.

Some level of differences does appeal by offering contrasts that we find attractive, but, overwhelmingly the empirical evidence is that we are drawn to those with similar values, beliefs, and world views to us. We simply avoid our polar opposites.

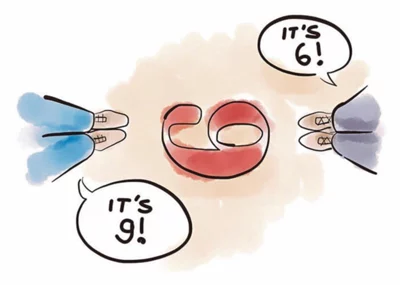

This error of thinking is called confirmation bias and it plays out in our personal relationships, social interactions, and professional lives.

There is hardly an aspect of our lives where we do not consciously or subconsciously filter out things we do not agree with and interpret information in a way that suits our thinking and interests.

Social media accentuates our problem by using sophisticated algorithms to register our interests and preferences (e.g. likes) and then feeds us more of the same, hence, creating giant echo chambers that strengthen our world views and drown out different views.

Confirmation bias, compounded with other thinking errors, has led us to the present post-truth era. There have been others before in history. In this era, even the horrific killing of 20 innocent young American children can be denied and their families persecuted for allegedly staging it.

In short, confirmation bias creates ridiculously toxic environments. It is also present in national policy making and its effects can be pernicious. Most of us should know that decisions ought to be made in an objective and analytical setting. They should make use of all information available and dispassionately evaluated.

But this is not how many major policy decisions are made. Instead, information is filtered to suit existing assumptions, beliefs and, very importantly, interests. Those with opposing views are more likely to be sidelined or delegitimised rather than heard.

Policymakers are usually people in authority and can wield considerable power to ensure that only their view is heard. Everyone and everything else is labelled academic or apolitical. Once a decision is reached, it is vigorously defended even in the face of contradictory evidence and strong arguments.

On May 9, Malaysians voted in a new government for the first time. The new government has different ideas about how things should be done, and, given what is known about the past and which has since been revealed, it has an extremely good case for its change agenda.

The reform of compromised and weakened state institutions and the crackdown on corruption are critically needed and widely supported by the voting public. The promised repeal of laws that stifle dissent and human rights and that contribute to non-transparency, unaccountability and abuse of power is something that every right-minded Malaysian should want.

But, so too, should be the goal of a mature, civilised, and inclusive dialogue on matters of national importance. As a country with extensive linkages to the rest of the world, Malaysians cannot continue with the proverbial “frog under the coconut shell” mentality.

The world today operates at a speed and complexity that defies simple yes-no solutions. In an everchanging political, economic, security and technological environment, desirable outcomes of decisions cannot always be assured.

A central element of good governance is an open learning and interactive environment, one where there is a plurality and diversity of responsible input. Instinctive decisions, or what one noted psychologist calls “fast thinking” has its place, but, there must also be “slow thinking” or more careful analyses and debate.

National dialogues on public policy must be safe harbours. Conscious decisions must be made to hold personal ideologies and even politics in check in the search for decisions that advance the nation’s interests and not a small group of parties or community’s interests.

Malaysia’s political system is designed to serve the greater good. As with any political system in the world, governments are expected to use their power to deliver. The way that power is applied today is as important a legitimising factor as elections.

A great deal is expected and challenges abound in the new Malaysia. More than ever, efforts must be made to correct our established confirmation bias.

Dato’ Steven Wong is deputy chief executive, Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia