AS an indication of how out of touch some international pundits of Asia are, they still call North-East Asia (China, Japan and Korea) “East Asia.”

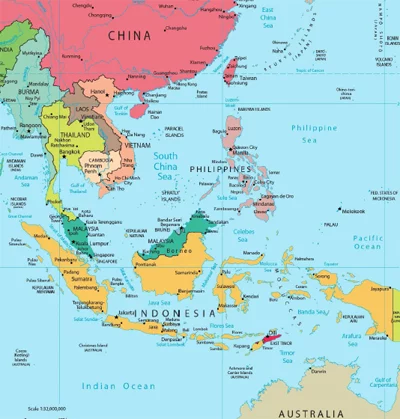

East Asia as a region comprises the sub-regions of North-East Asia and South-East Asia, the latter being the countries of Asean and Timor-Leste. The Asean region developed steadily with peace and prosperity as its watchwords. It became known as a region consistently posting some of the highest growth rates in the world. Yet Asean and its member countries were severely constrained by a lack of economic weight and global reach.

Asean’s diplomatic clout is fine, but South-East Asia as a region falls short of economic heft in a rapidly globalising world. Nonetheless, the forces of globalisation themselves would take care of that with growing economic integration within East Asia.

North-East Asia included two of the world’s three largest economies, so as a region it had no problems of limited reach or heft. Despite global constraints, China on the whole continued to grow. As the economies of North-East Asia and South-East Asia grew more integrated, growth in East Asia as a whole would soon reach an altogether different plane. Studies generally find intra-regional trade surpassing foreign direct investment (FDI). A 2009 study found that tariff reductions as well as closer monetary cooperation among East Asian countries made sense.

A report by the Asian Development Bank Institute last year acknowledged the impressive growth of East Asia’s intra-regional trade ratio over the past 55 years. It noted how trade had become “more functionally linked to international production networks and supply chains” as well as FDI in the region. This indicated East Asia’s deepening regionalisation. Typically, after Japan’s export of capital to South-East Asia in the 1970s and 1980s, China took up the slack as Japan’s economy levelled off from the early 1990s.

In 1990, ISIS Malaysia and Prime Minister Tun (then Datuk Seri) Dr Mahathir Mohamad worked on a proposal for an East Asia Economic Grouping (EAEG). It was time for East Asia to come into its own. When Chinese Premier Li Peng visited Kuala Lumpur in December 1990, Dr Mahathir proposed the EAEG to him. Li Peng accepted and supported it.

The idea had not been discussed within Asean before. Indonesia, the biggest country and economy regarding itself the region’s “big brother,” felt miffed that it had not been consulted about the plan. Singapore’s position, traditionally more aligned to a US that was not “included” in the East Asia proposal, was slightly more nuanced.

Lee Kuan Yew, upon becoming Senior Minister just the month before - and on the cusp of the Cold War’s demise - still preferred an economic universe defined by the West. At the time this was the European community and the Uruguay Round as an outgrowth of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (Gatt). It was still three years before the European Union (EU), and four years before the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta).

Generally the world was still beholden to Western economic paradigms and game plans. The EAEG was thus seen as the work of some upstart Asians, in turns brash and occasionally recalcitrant. Most of the six Asean countries, like South Korea, accepted the EAEG even as they tried to learn more about it. But it was still at best tentative. The EAEG’s critics however proved more vocal. US President GHW Bush and Secretary of State James Baker wanted to crash the regional party by becoming a member also, or else would see the idea crash.

The Uruguay Round was then seen to be quite rudderless, and Apec, itself formed just one year before, appeared fumbling in the doldrums. The EAEG, misperceived as an “alternative”, would be thinking and acting outside the box. An energised Asia owing nothing to Western patronage was far too much for an Occidental-conceived world order to contemplate, much less accept.

Malaysia tried to soothe anxieties about the EAEG by emphasising its soft regionalism. It was to be only “a loose, consultative” grouping and no more. Why should a booming, rapidly integrating East Asia be deprived of a regional economic identity, when Europe and North America could develop their own?

However, the EAEG’s public relations campaign proved too little too late. The idea, albeit now conceived as an Asean project, lacked traction and ground to a halt. Singapore saw its merits and tried a different tack. Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong proposed an East Asia Economic Caucus (EAEC) within Apec, allaying fears of an insecure US that this would remain within the ambit of a US-dominated Apec.

Several political speeches and conference papers later, the EAEC idea also failed to germinate. A Bill Clinton presidency was lukewarm-to-cool to the idea, still without the encouragement Japan needed for a nod.

A flourishing East Asia would be left without a regional organisation of its own, again. In 1997 the devastating Asian economic and financial crisis struck, hitting South Korea, Thailand and Indonesia particularly badly. If the EAEG had been in place by then, greater regional cooperation and coordination would have helped cushion the shocks.

Suddenly, South Korea took the initiative to push East Asia into forming a regional identity: Asean Plus Three (APT). This grouping would consist of the same EAEG countries. Japan this time was more accommodating, and the APT was born. For decades, “the West” led by the US was identified with open markets and free trade. But now a Trump presidency deemed protectionist, even isolationist, is hauling up the drawbridge and raising the barricades with tariffs and other restrictive measures.

These are aimed at allies and rivals alike, whether in Europe or Asia. Equivalent countermeasures have been launched, and the trade-restraining spiral winds on. China, by now identified globally as a champion of open markets and free trade, has called on Europe to form a common front. Strategic competitors are making for strange trade bedfellows and vice versa.

Dr Mahathir was on his annual visit to Tokyo last month for the Nikkei International Conference on the Future of Asia. He duly revisited the idea of an East Asian economic identity and community. For emphasis, he added that he preferred this to a revised Trans-Pacific Partnership that the US has now rejected. How would an EAEG now play in today’s Japan and East Asia? More to the point, how would it play in Washington? The answer may still determine its prospects in Tokyo and East Asia as a whole.

It is possible that the US has become too tied to the idea of battling trade skirmishes, if not outright trade wars, with any presumed adversary to have time to frown on an EAEG. Dr Mahathir has noted how this is the time for such a regional grouping, since we still need it and particularly when the US is helping to justify it.

It is also conceivable that Japan today is more open to the EAEG, just like with the APT post-1997. The more the rhetoric of a US-China trade war rages, the more likely East Asia can finally develop a regional economic identity of its own.

Even a US-EU trade conflict will do. East Asia should not be too choosy about its benefactors.