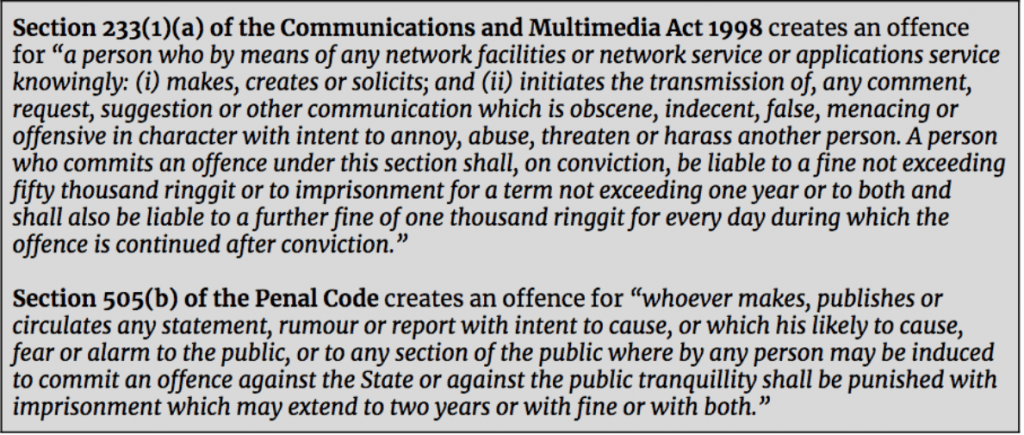

The COVID-19 infodemic has shown that content needs to be regulated. The continued reliance on Section 505(b) of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 means continued exposure to risk of abuse. In light of this, what is the way forward towards the twin goals of addressing the infodemic and better protecting free speech?

The state and cost of the infodemic

False information and rumours thrive on fear and uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic offers plenty of both. Due to its novelty, room was created for both the unintentional and intentional spread of false information – known as misinformation and disinformation respectively. The proliferation of false information online has led the World Health Organisation to declare that there is now an “infodemic” – “an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not, that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it”. The proliferation of false information alongside outbreaks of diseases are nothing new.

But as Renee Diresta, technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory has observed, the spread of false information following the COVID-19 outbreak can be differentiated with the Ebola and Zika outbreaks as the latter two were relatively confined geographically. This is contrasted with COVID-19, which at the time of writing affects 195 countries, making it the first truly global pandemic in the age of social media.

What this means is that false information created in one country experiencing COVID-19 could very well spread globally online. Permitting this is the frictionless nature of social media platforms which allow content to be published without moderation and fact-checking, preconditions that are associated with more formal publications. This allows false information to spread faster and wider than before.

Signalling the extent of this is that the CoronaVirusFacts / DatosCoronaVirus Alliance Database – which includes more than 100 fact-checkers around the world – has fact-checked more than 1,500 falsehoods surrounding COVID-19. Meanwhile hinting at the extent of the problem locally, as of 26 March 2020, there have been 187 debunks of COVID-19 false information on SEBENARNYA.MY, a fact-checking site under the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia Malaysia.

Worryingly is that despite a coalition of social media and technology giants – including Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Reddit, Twitter, and YouTube – pledging to combat “fraud and misinformation about the virus”, these efforts to remove false information would, by nature, only be after the fact the content has been published. This means that users could have already been exposed to false information.

Combining this with the infodemic’s sheer volume suggests that even if the false information were to be taken down or fact-checked, users who have already repeatedly been exposed to the false information could continue believing in it due to the illusory truth effect. The illusory truth effect occurs when repeating a statement increases the belief that it’s true even when the statement is actually false.

A further consideration that needs to be taken is how false information spreads not only on social media, but communication applications as well. For example, according to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) Internet Users Survey 2018, WhatsApp is the most popular communication application in Malaysia with 27.2 million users. With its end-to-end encryption technology, efforts to identify and counter false information on WhatsApp and other communication applications pose a Herculean task.

To be sure, leaving health-related content unregulated is untenable. This is because the marketplace of ideas – where good ones are presumed to trump the bad – fails when the spread of false information exploits evolutionary biases in human cognition. These are the very same cognitive biases that explain why humans are more engaged with information on potential threats – as compared to other kinds of information – as it offers an advantage in keeping humans from danger, and consequently ensuring survival.

For example, considering how widespread COVID-19 is, it would be natural for those who are concerned to seek means to protect themselves, and/or remedies for the virus. As search results would be tainted by the infodemic, users could be exposed to false information potentially leading to a false sense of security, and in some cases, even death.

Additionally, content also needs to be regulated as false information during times of a health crisis can lead to excessive panic in the population. This can result in people flocking to supermarkets to panic buy groceries at the expense of vulnerable groups and the effectiveness of social distancing measures put in place.

But the larger danger posed by an untreated infodemic is a continuous pollution of the information environment which decays, devalues and delegitimises the voices of experts and authoritative institutions. This may result in lowered trust towards experts and institutions – such as those responsible for public health, which could negatively impact their legitimacy when implementing policies that require whole-of-society buy-in such as movement control orders.

The response to the infodemic

As of 23 March 2020, there have been a total of 43 investigations for either “improper use of network facilities” under Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) 1998 or “statements conducive to public mischief” under Section 505(b) of the Penal Code. Of this amount, six individuals have been charged under Section 505(b) of the Penal Code, while five are being investigated and have had their statements recorded under Section 233 of the CMA 1998.

Several lawyers have come out in defence of the utilisation of Section 505(b) of the Penal Code to regulate the spread of misinformation pertaining to COVID-19. Among others, they argued that its provisions are more specific in its applicability, and requires satisfying the higher threshold of “affecting public tranquility”, as opposed to the lower thresholds of the statement only needing to be intended to “annoy” under Section 233 of the CMA 1998, or only needing to be false under Section 4 of the now repealed Anti-Fake News Act (AFNA) 2018.

While this much is a given, it is also important to note that Section 505(b) of the Penal Code is not the panacea to cure the infodemic. With its provisions not requiring an element of falsehood, the provision could – theoretically – be applicable to cases whereby despite the statement being accurate and truthful, the maker of the statement could still be found guilty if the statement affects public tranquility. Here, it would not be far-fetched to argue – hypothetically – that Section 505(b) of the Penal Code can be abused to target journalists who break public interest stories, which by its very nature affects public tranquility.

That said, it needs to be admitted that legislations are rarely perfect, and perfect should not be the enemy of good. It is undoubted that even the deeply flawed AFNA 2018 and Section 233 of the CMA 1998 would be helpful to address the infodemic today – what more “better” crafted legislation like Section 505(b) of the Penal Code. But that said, it is worth remembering that continued exposure to the risk of abuse is a huge price to pay in retaining such vaguely worded, broadly applicable legislation.

Considerations in treating the infodemic

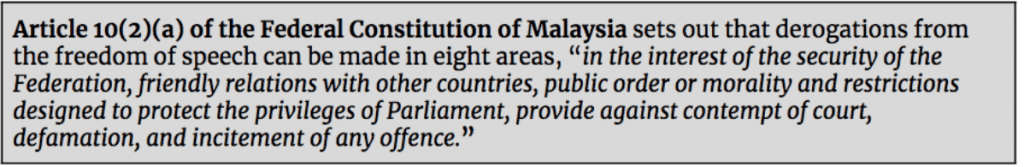

Considering policy options moving forward, the introduction of any new legislation to regulate content will inevitably raise concerns of censorship and its potential chilling effect on free speech. In assuaging those concerns, the government must avoid usage of genuine cases where speech needs to be regulated – as with now during the COVID-19 pandemic – as a fig leaf to justify far reaching intrusions on individual liberties.

That said, it needs to be underscored that the freedom of speech, as provided under the Article 10 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, is not limitless as derogations are permissible. This being the case, it does not mean that the government is granted carte blanche in limiting free speech, as any legislation needs to be for a legitimate objective, and measures taken must be proportionate to that objective – as required by the rule of law. This will ensure that free speech is safeguarded by curtailing it only to the extent absolutely necessary, while mitigating the chances of indirect censorship.

Further, by being clear on its objective and how it would apply, the proposed legislation will better achieve legal certainty – ensuring that the general public are better able to regulate their conduct accordingly. This is as any legislation should never be intended to solely prosecute, but rather also set norms of what is acceptable.

Section 233 of the CMA 1998 and Section 505(b) of the Penal Code, which are currently being used to prosecute those who spread false information and rumours, fail to satisfactorily achieve the latter. This is as they do not communicate clearly the kinds of content that are unacceptable beyond vague and broad concepts like “affecting public tranquility” and intended to “annoy” – which leaves the public unable to regulate their conduct accordingly.

Moreover, there needs to be an avoidance of simplistic thinking in diagnosing the problem. One example of such thinking is that the infodemic is caused by the lack of stringent regulations.Proponents of this line of thought argue that stringent regulations are required to deter people from creating and sharing false content. While appealing to common sense, Nagin suggests that “certainty of apprehension, not the severity of the ensuing legal consequence, is the more effective deterrent”. This makes an important point to appreciate, that heavier punishments are not the end all, be all to address the infodemic.

As certainty of apprehension plays an important factor in creating an effective deterrent, it is crucial that any proposed legislation to regulate false information is complemented with technical expertise to identify, track and detain the creators and sharers of disinformation. With regards to this, it needs to be underscored that those who are truly motivated to create disinformation and cause harm could potentially be hiding their true identities through sockpuppet social media accounts, or by utilising off the shelf virtual private networks (VPNs), or even conduct their operations from other jurisdictions putting Malaysian legislations out of reach.

On the latter, even if the proposed legislation contains provisions for extraterritorial applicability, the probability of the other country rendering mutual legal assistance for investigation and extradition is easier said than done.

Lastly, the government must also resist calls from certain quarters of society, including former de facto Law Minister Azalina Othman, to reinstate the repealed AFNA 2018. This, they argue, would act as a vanguard against the spread of false information. Here, it is worth remembering that the repealed Act was incredibly vague in its definition, and disproportionately broad in its applicability — flying in the face of even the most liberal of readings of basic free speech standards.

Policy response

The current pandemic has highlighted the clear need to address the health-related infodemic. Maintaining the current set of legislations – while convenient now to address the misinformation and disinformation associated with COVID-19 – would mean continued exposure to the risk of abuse, while a wholesale repeal would create a lacuna in the law.

As scientists are now warning that the COVID-19 pandemic would be a protracted affair leading to new normals – the introduction of a new punitive legislation to regulate COVID-19 false information is needed. To that end, in ensuring that free speech rights are curtailed only to the extent absolutely necessary, the proposed legislation needs to be specific in its objective; towards assuaging concerns of censorship, the legislation needs to be clear in its applicability, and; to prevent unjust repercussions, the sentencing must be proportionate to the crime.

a) Specific objective

Policymakers need to introduce a punitive legislation, applicable to all mediums – including social media and communication applications – that specifies the types of false information that are unacceptable during the COVID19 pandemic. This will have the simultaneous effects of educating the public who will then be better able to regulate themselves, sending a coercive signal to would-be offenders, and reducing the risk of abuse.

b) Clear applicability

Further to that, the proposed legislation should also only apply to COVID-19 related disinformation (the intentional creation and/or spread of false information) that causes actual harm. What this means for the proposed legislation is that it should be insufficient for guilt to be established based solely on content being false in nature, but it must also be intentional, and be proven to have, or is reasonably likely to cause harm. With that, only those who are intentionally creating and sharing false information to cause harm will be prosecuted, while the honestly mistaken will not.

To that objective, the proposed legislation should apply to:

- Disinformation on the spread of COVID-19 that incites panic;

- Disinformation meant to influence people into acting against recommended practices set out by health authorities;

- Disinformation on non-scientifically proven remedies for COVID-19; and

- Disinformation on the basis of impersonating authorities.

c) Proportionate punishment

In determining punishment, proportionality – a general principle in criminal law used to convey the idea that the severity of the punishment of an offender should fit the seriousness of the crime – needs to be by design, and not left to chance.

Towards that end, when determining punishment, the following must be taken into account:

- To what extent was harm caused, or reasonably likely to have caused due to the disinformation;

- How widespread was the disinformation;

- Was the creator and/or sharer of the disinformation a figure of authority, or was impersonating a figure of authority;

- Was the creator and/or sharer of the disinformation part of a larger coordinated group;

- What was the general context in which the disinformation was created and/or shared; for example, false information shared during a pandemic causes, or could reasonably cause more harm than it would during ordinary times.

Conclusion

As laid out above, the proposed legislation that is specific in its objective, clear in its applicability, and proportionate in its punishments can satisfactorily meet the goal of addressing the ongoing COVID19 infodemic, while striking a better balance with free speech rights. Further, with a more specific legislation to regulate COVID-19 false information, the government will communicate unequivocally the kinds of content on COVID-19 that are unacceptable, allowing the public to better regulate their conduct.

While acknowledging the relative “advantages” of vague and/or broad legislations like Section 233 of the CMA 1998 and Section 505(b) of the Penal Code – it needs to be emphasised that despite “drastic times calling for drastic measures”, it does not, and should not grant government carte blanche to intrude on, or steamroll over individual liberties. This would not only contradict the spirit of the constitutionally-guaranteed freedom of speech, but also take advantage of the people who would most likely choose immediate interests such as health and safety over more abstract concepts like free speech.

Further, as the proposed legislation would only be applicable to disinformation, and not misinformation, the risk of making criminals out of the uninformed will be greatly mitigated. This distinction is important as it would better acknowledge how at these uncertain times, the public is primed, due to evolutionary biases, to crave and share information that could protect themselves and/or be beneficial for survival – even ones that are not scientifically proven.

That said, any punitive legislation – whether existing or being proposed – needs to go hand-in-hand with other measures to build society’s resilience to the infodemic. These measures should include introducing government oversight on social media platforms, increasing the public’s digital literacy skills, and ultimately clear, consistent, and transparent communication from the government.

As Yuval Noah Hariri opined, “harsh punishments aren’t the only way to make people comply with beneficial guidelines. When people are told the scientific facts, and when people trust public authorities to tell them these facts, citizens can do the right thing even without a Big Brother watching over their shoulders. A self-motivated and well-informed population is usually far more powerful and effective than a policed, ignorant population”.

While on one hand this much is true, on the other hand is that with movement control seemingly becoming the new normal, meaning more people will spend more time indoors and online, the need for punitive legislation should not be downplayed. It should, however, as the proposed legislation makes clear, be reserved – by design – for those who intentionally cause harm by creating and sharing disinformation.