Article by

Bridget Welsh and Calvin Cheng

first appeared on MalaysiaKini on 18 April 2020

While we rightly think of vulnerable communities as the poor, there is another form of insecurity being shaped during Covid-19: the young people who are on the frontline of the economic effects of this deepening crisis. Across the world, economies are being devastated and millions are being put out of work. Malaysia – with its slowing economic before Covid-19 – is facing unprecedented serious challenges that will extend long after the Movement Control Order (MCO) is over. The stark reality is that millions of Malaysians will lose their jobs in this global downturn. Factories are already closing and many businesses closed down will not start up again.

For Malaysia’s nearly 6 million young people (15-29 years old) in the labour force, Covid-19 will be especially damaging. They face the highest risk of unemployment and precarity; their job opportunities will be severely curtailed by the contraction of the job market and with their comparatively lower incomes many will struggle to feed their families. As many have observed, while the old may face greater health hazards from the global coronavirus pandemic, it is the young who will bear the brunt of the socio-economic fallout.

The generational impact of Covid-19 cannot be ignored. Millennials (Gen Y born from 1980) are now facing the second economic downturn in their lifetime, with the earlier 2008-2009 recession. Post-millennials (Gen-Z under 25) are barely getting on their feet, before the economy is being cut from under them. Already younger Malaysians face more obstacles in terms of housing affordability, higher debt levels, lower wages, and a decline in inter-generational social mobility.

While economic growth and technological advancement have given many young people greater opportunities to hone their talents and live their dreams, many young Malaysians are being left behind. There are many who have not been able to complete secondary school and still others who manage to graduate from university but lack the necessary skills to secure gainful employment. Others are trapped in underemployment and low-paying jobs, aiding in the perpetuation of inter-generational poverty for some families, especially outside of the Klang Valley.

This piece takes a look at the situation faced by younger Malaysians, concentrating on those under 30. We argue that Covid-19 will leave an imprint on the younger generation.

As in our earlier piece, our discussion draws from available data and examines the impact of this multi-faceted socio-economic crisis Malaysia and the world is facing. Given the reality of hardship young Malaysians will face, and their political clout, greater attention to the design of policies and interventions governing the labour market for young people will be essential moving forward.

Youth Unemployment in Crisis

Young workers are disproportionately vulnerable in times of economic crises. Already faced with higher rates of unemployment and underemployment compared to the overall labour force, young people are often the first to lose their jobs when economic conditions worsen.

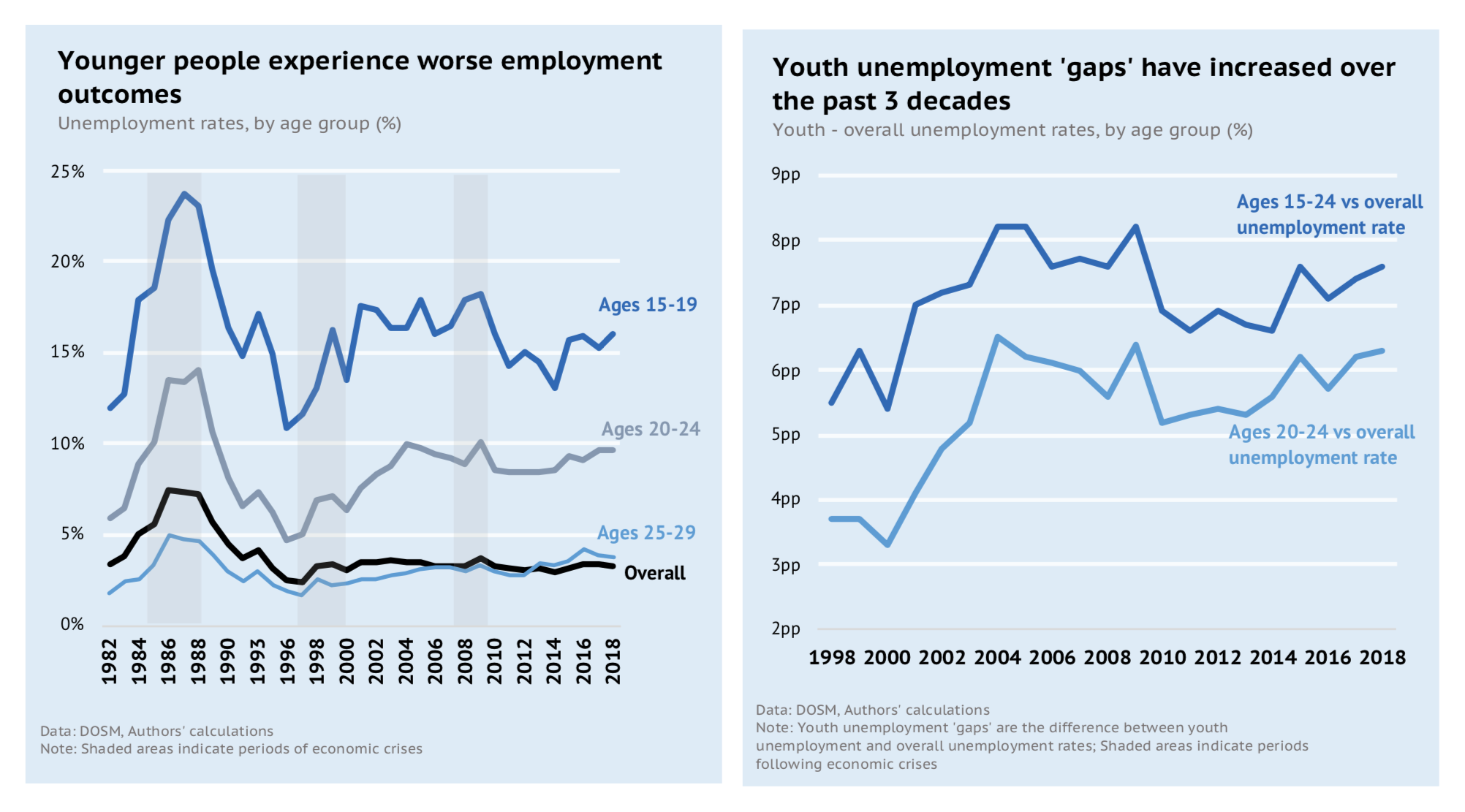

In Malaysia, this is no different. Malaysian data indicates that unemployment rates for the youth are persistently higher and tends to be much more sensitive to economic conditions than the overall unemployment rate. Additionally, youth unemployment rates get higher the younger the age group. Teenage jobseekers (aged 15-19) are almost 1.7 times more likely to be jobless than young adults (aged 20-24) – and almost five times more likely to be unemployed than the overall labour force, (including those 25 and over). This makes sense considering that teenage jobseekers almost exclusively do not have a tertiary education, while young adults in general are typically first-time labour market entrants who have not had time to build up the necessary social and human capital networks.

Additionally, the challenges for Malaysia’s youth are mounting: as shown in the chart below, data suggests that it’s getting considerably harder and harder for young Malaysian jobseekers to find employment compared to the overall population. The gap between younger Malaysians and others in the labor force is widening.

Worse still, we know that periods of unemployment can create persistent lifetime effects for the youth. A large body of evidence suggests that graduating into a weak labour market and being unemployed while young has long-lasting implications on future income, lifetime savings and employment prospects for decades to come.

In times of crises like these, youth unemployment rates tend to rise higher and more rapidly compared to overall unemployment, as young workers tend to work in part-time, temporary, and/or informal work—often in the services-related sectors anticipated to be the hardest hit by the ongoing crisis.

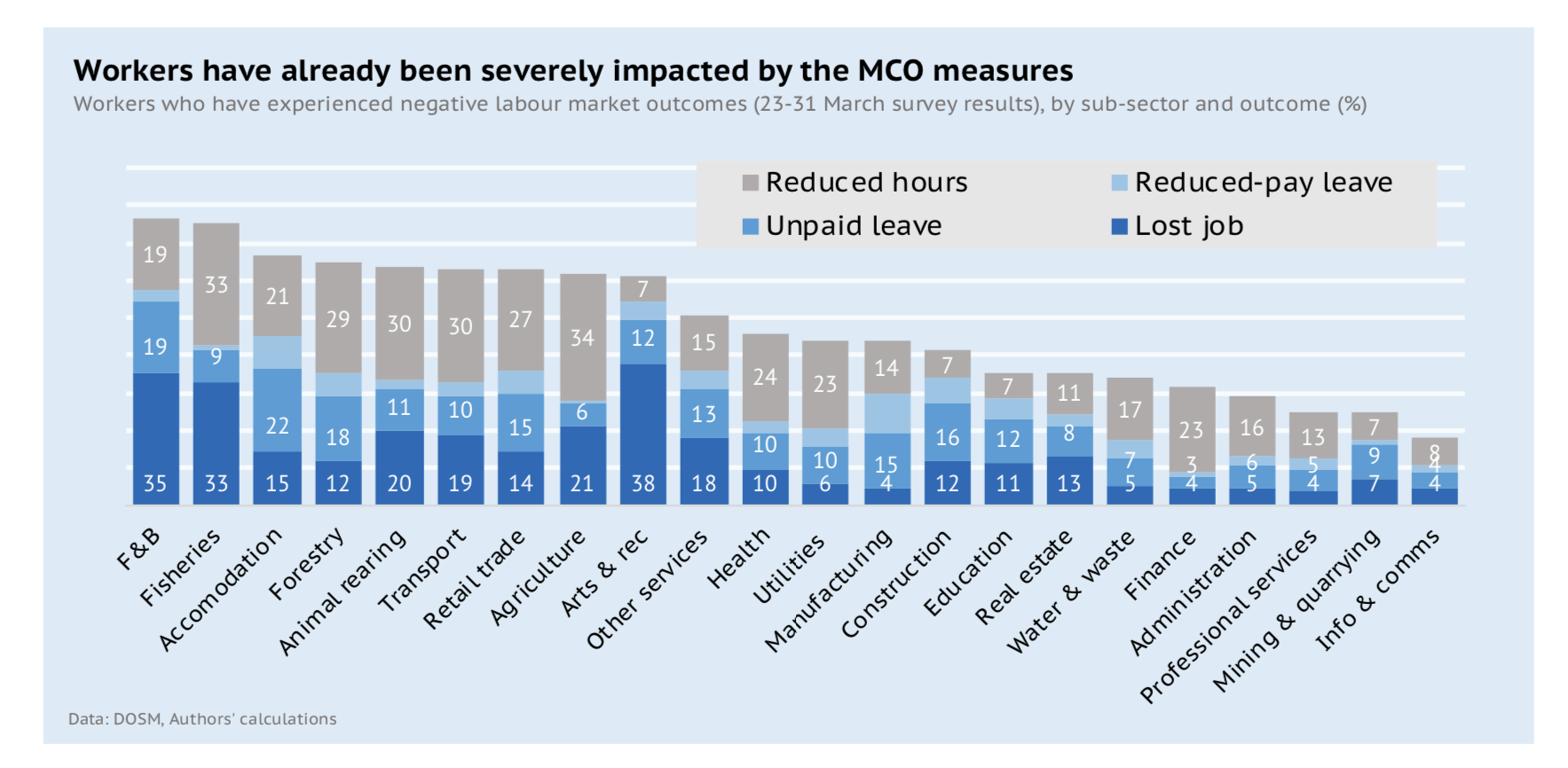

Preliminary data released by the Department of Statistics indicates that the imposition of the MCO has impacted a number of sectors in particular, as shown below. Based on past patterns, we can expect youth unemployment rates to rise sharply beyond past levels to new highs of between 15 to 25 percent depending on the age cohort, or worse yet, even higher.

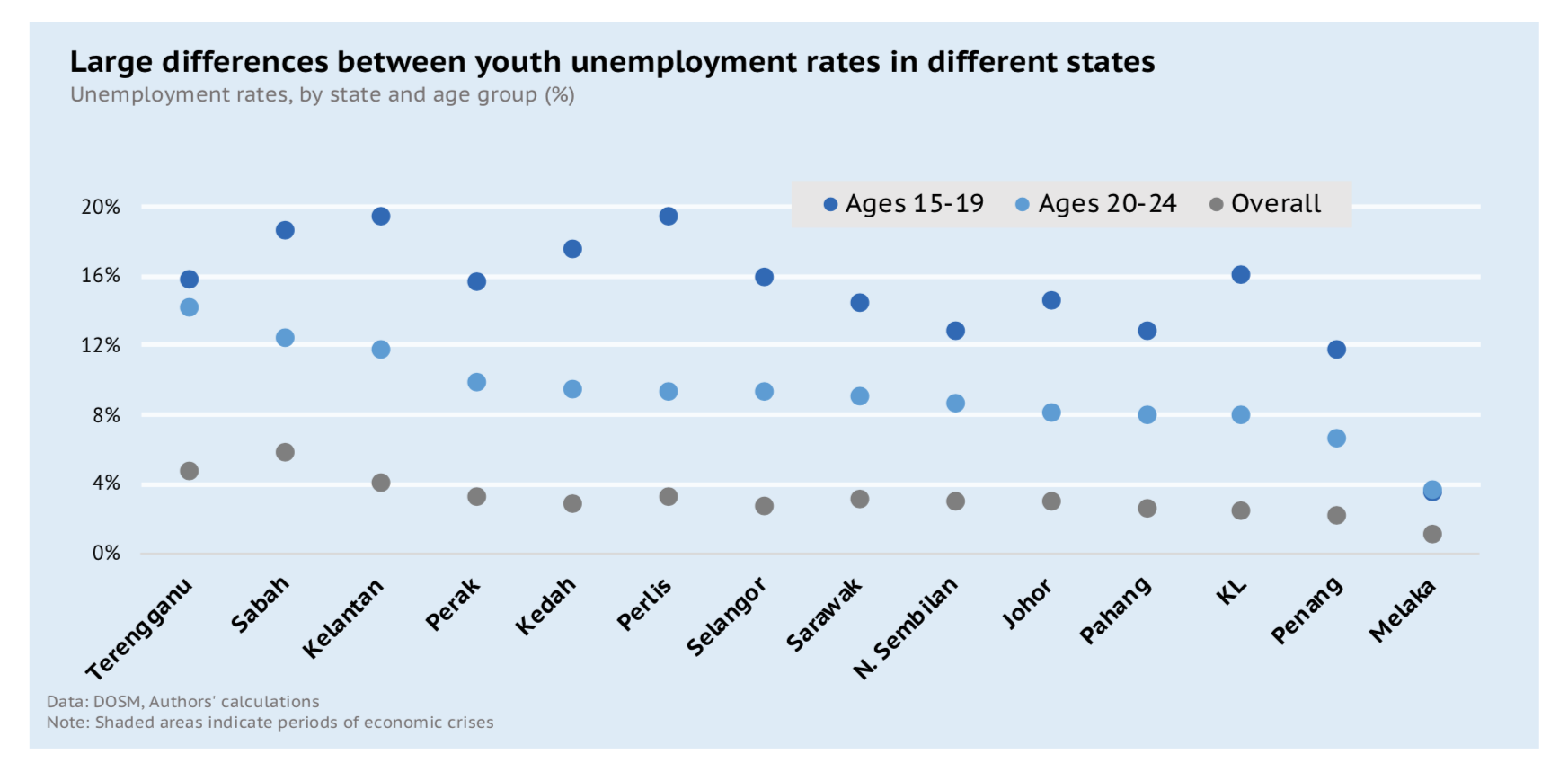

Youth unemployment doesn’t just vary by age, it varies by state as well. There are significant geographical and income components to youth unemployment in Malaysia. Conditions are better off with greater job opportunities on the West Coast of Malaysia, barring exceptions such as Perlis and Perak. But prospects are much bleaker in lesser-developed region in the East. As a young jobseeker, the worst states to look for a job in Malaysia are Terengganu, Sabah, and Kelantan, which have the highest youth unemployment rates in Malaysia.

This is further supported by the Ministry of Education’s annual Graduate Tracer Study which indicates significant disparities in the prospects of lower-income graduates and higher-income graduates – and between more developed and less developed states in Malaysia. It is not a coincidence that states with the greatest poverty are also the states in which the younger members of the labor force face adverse circumstances – Sabah and Kelantan.

A Really Tough Job Market

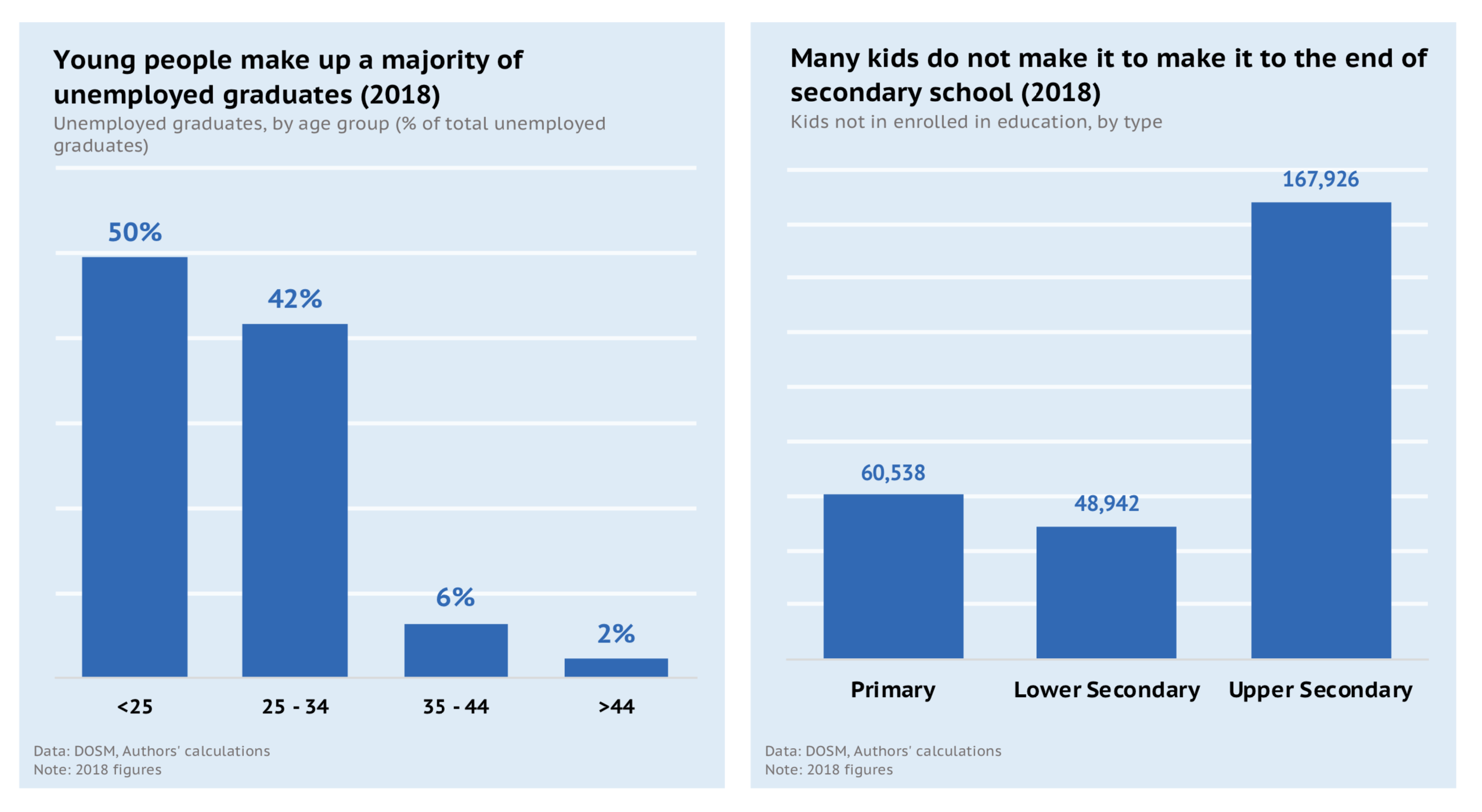

Currently half of all unemployed graduates, about 80,300 persons, are made up of young people below 25 years of age. This points to a real problem, as it suggests that Malaysian universities are not providing graduates with the skills for the marketplace. Numerous surveys of companies report that graduates are often unemployable due to skills deficiencies, which raises real questions about how universities are adapting to shifting demands of the workplace. There are particular shortcomings in basic skills of writing, verbal communication and problem solving. Covid-19 will only worsen the situation, exacerbating this gap between skills and employment as the number of available jobs drop. This is why Malaysia needs to be thinking ahead about how to train young people for the post-Covid environment.

At the same time graduates are saddled with high student loans. A recent ISEAS paper by Wan Saiful Wan Jan, the chairman of Malaysian National Higher Education Fund Corporation (PTPTN), highlights that the low repayment rates and student loan defaults were disproportionately among the Bottom 40 (B40) income earners. His survey showed a staggering rate of 87.7% defaulting due to a lack of financial security. As low-income borrowers make up the majority of those taking loans, this involves large numbers. The paper points out that an average of between 160,000 to 180,000 students become new PTPTN borrowers every year, costing PTPTN between RM3 billion to RM3.5 billion annually. Since it was set up twenty-three years ago PTPTN has disbursed RM56 billion to over 3 million students but is itself in financial trouble due to the problems of its financial model and repayment issues. The problem of student debt among youth is compounded when one considers car payments, housing loans and other costs of living with current comparatively low wages—as young people make up a large proportion of Malaysians with high household debts relative to their incomes.

The stress these financial conditions place on young people, especially those with families, is intense, contributing to debilitating effects on mental health and strain within families. More often than not, there is a frustration and lack of confidence among some youth which contributes to greater vulnerability in facing a scarce job market, forcing young people to turn to their parents and family for support and in some cases contributing to other social problems facing young people, notably drug use and crime.

Yet, for all the challenges young graduates face—there are also many young people who do not even make it past secondary education. These are dropouts from the educational system who enter the labour market. Official numbers show that about 218,868 teenagers in 2018 were not enrolled in secondary school, but even these numbers may not fully capture the scope of the problem. We estimated that his pattern has been going on for years, suggesting that at least 1.5 million Malaysians have not graduated from high school but are part of the work force. Latest labour force survey data indicates that at least an estimated 11.1 million, or about 71% of the Malaysian workforce lack any type of tertiary education. School dropouts often face the most financial obstacles and challenges with social mobility over their lifetime. The economic realities surrounding Covid-19 will only further depress their prospects.

Youth Economic Vulnerability

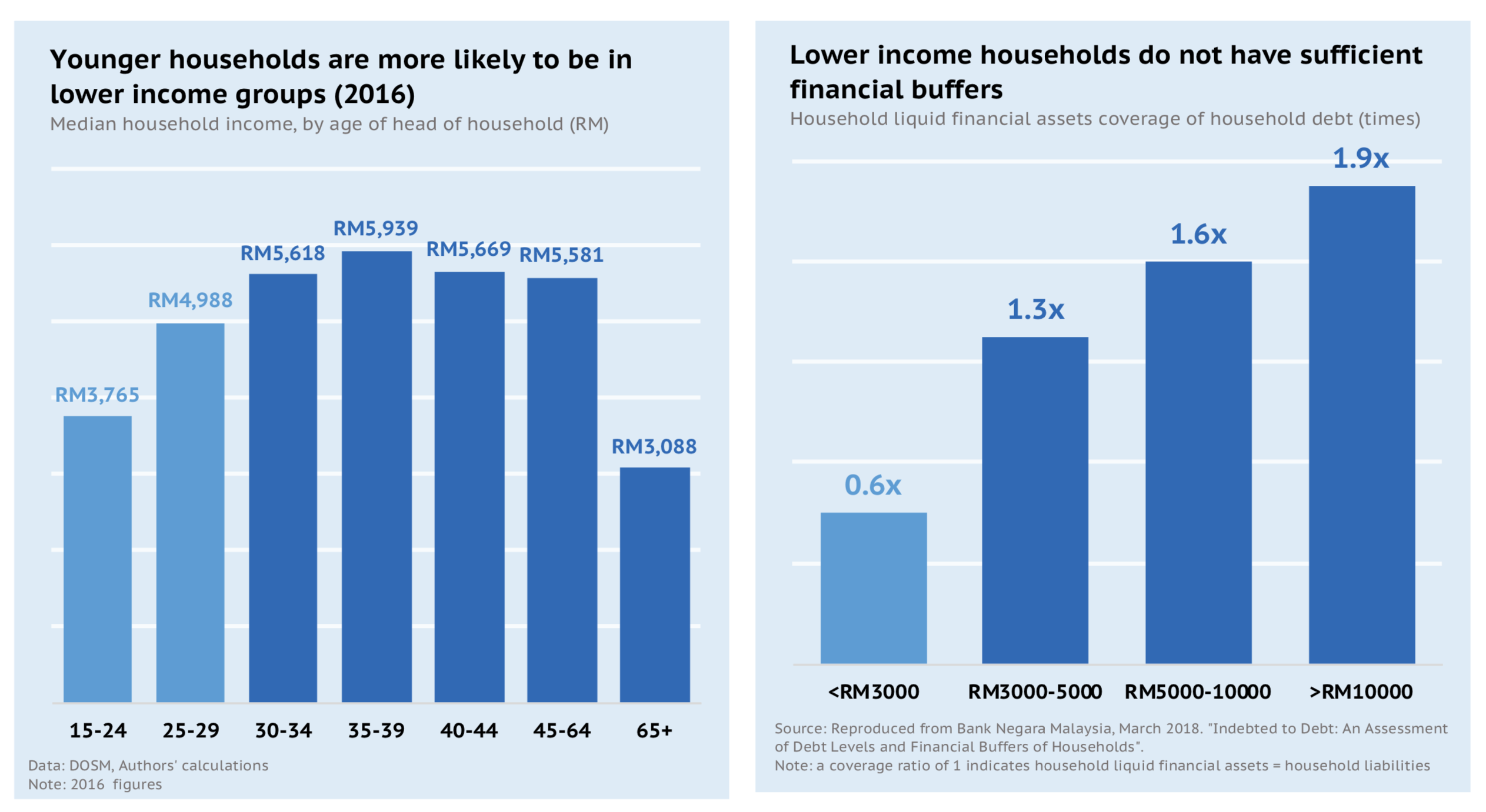

Besides being exposed to job losses and reduced opportunities, younger individuals and households are also least able to withstand a fall in their incomes due to their lack of financial buffers and higher debt levels.

Data shows that younger households have the lowest median incomes of any age group, excluding those who are retired. This is compounded by the fact that these households are often with young families to take care of, which adds to their monthly expenses. A 2018 Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) paper reveals that lower-income households, of which the young make up a large proportion of, are likely not to have sufficient available funds to offset their debt obligations. Indeed, the authors’ calculations showed that just a 10% decline in household income would increase the share of households with insolvency problems by more than 5%. With the amount of households reporting a complete loss of income during the MCO, the current situation for younger households may prove to be far more dire than any previous estimates.

Young Political King Makers

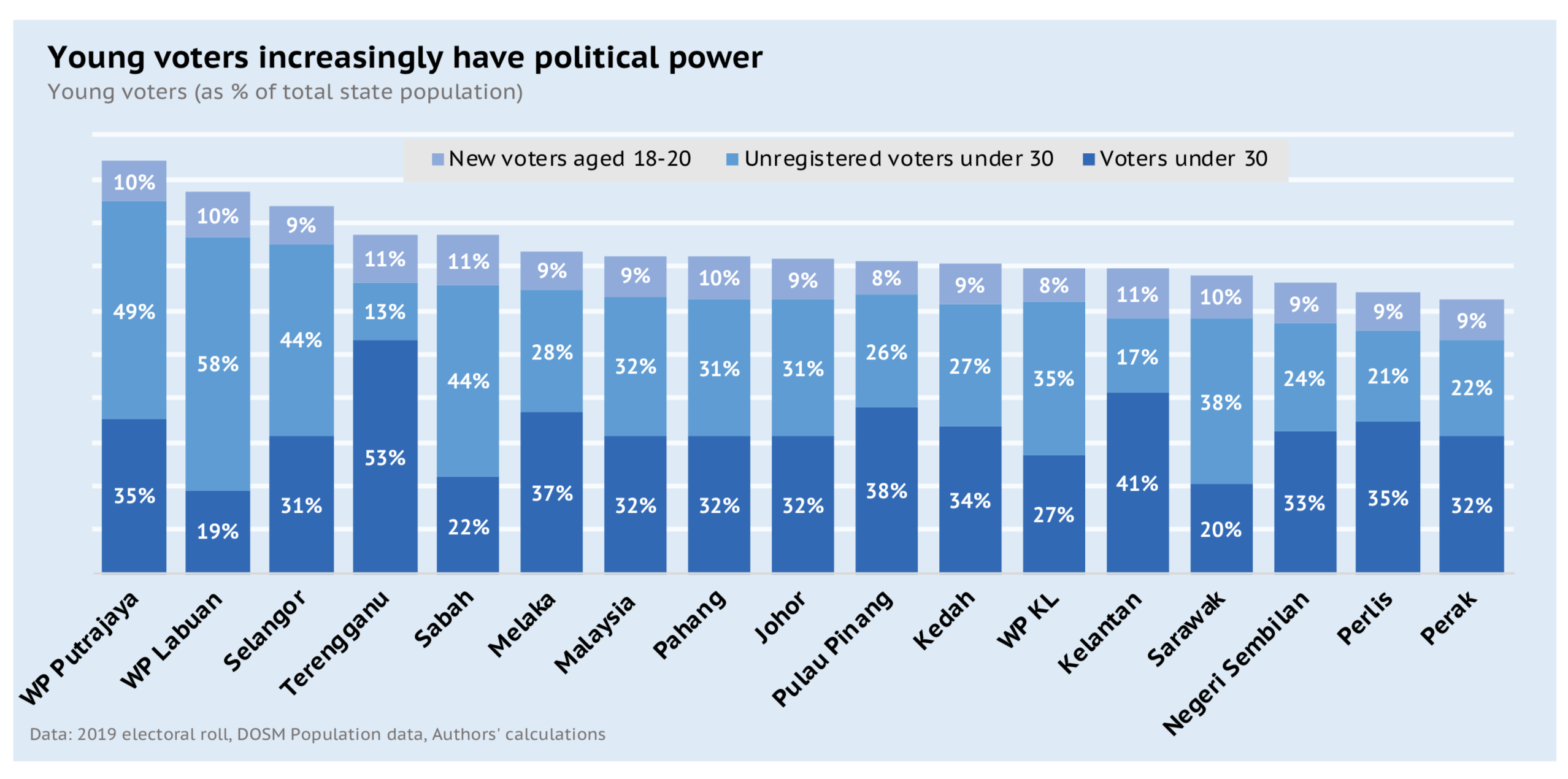

Despite the harsh realities faced by younger Malaysians, they have political clout. For the past three elections, the youth vote was decisive in shaping the outcome. PH was brought to power by younger voters. Whoever is elected in GE15 will similarly face this group of younger Malaysians that comprise 32% of the registered electorate. Disproportionately registered younger voters are especially important in Kelantan and Terengganu, comprising 53% and 42% respectively.

The chart also shows that many younger Malaysians are not registered, which nationally currently make up 32% of the population of this age cohort. The number of unregistered young Malaysians in Selangor (44%), Sabah (44%) and Sarawak (38%), highlighting that young people are an untapped reservoir for political change – if they register (which we hope they do).

The bipartisan support for the Undi18 initiative to lower the voting age to 18 and automatically register younger voters last year will further shift the balance of political power toward the youth. It is estimated that over 2 million younger voters will come into the electorate by 2022 (an average of 9% of the voting population). The chart shows that they will be especially politically impactful in Kelantan, Sabah and Terengganu, but the numbers will affect close races across the country. Given Malaysia’s fragmented political contests, these votes will matter. What will be especially important is that new additions of young voters will be on the electoral roll, so their potential influence could be especially meaningful if they vote. Economic crises have shown that people come to the polls angry, and often punish those in office. Politicians and policymakers who ignore this group do so at their political peril.

Limited Relief for Youth

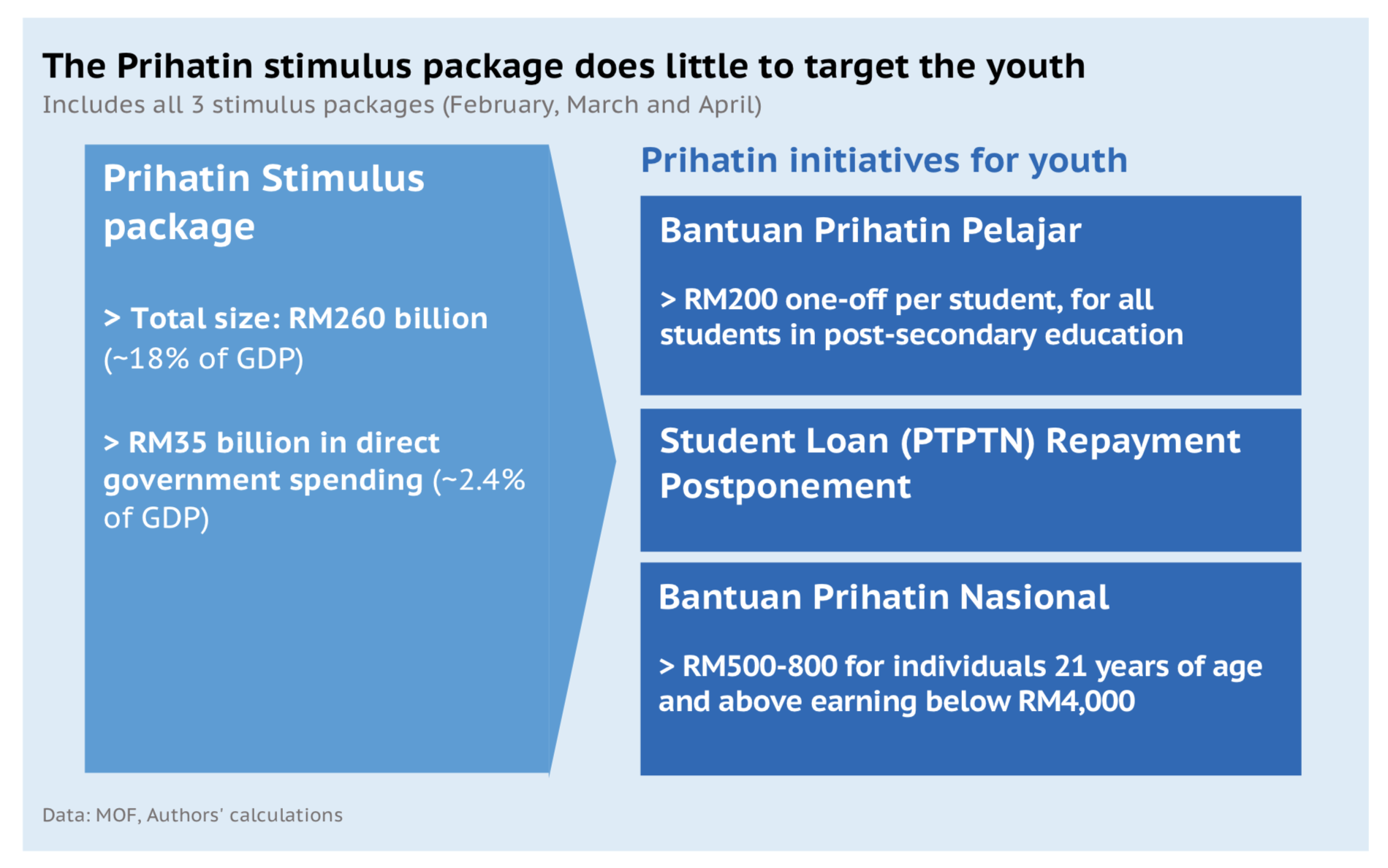

To date, the government’s response has yet to reflect how serious the effects of Covid-19 are on the youth. The Prihatin Covid-19 relief package has only a limited number of interventions targeting young people. The measures include student loan deferments, a one-off RM200 payment for all post-secondary students and inclusion in the Prihatin cash transfer based on income for those above 21, shown below. Importantly, those working and no longer in school under 21 appear to be excluded from benefits – arguably among the most in need in terms of income and insecurity. This could be easily corrected.

These measures however are not enough. There is an urgent need to engage in meaningful reform to address underlying issues to ameliorate the negative impact of Covid-19. In keeping with our aim to offer constructive suggestions to address Covid-19, we offer five additional concrete ideas for consideration.

First, the government can strengthen private-public sector partnerships through incentives to hire, retain and train young employees. Some countries, such as Singapore, adopted similar measures after the 2008-2009 downturn. Employer surveys frequently cite the lack of both soft skills and industrial training experience of recent graduates. This collaboration would have the benefit of addressing some of these mismatches between skillsets and younger workers.

Second, the government should consider ramping up training for younger Malaysians, not just those in the Klang Valley, but those in the states hardest hit by youth unemployment. Specifically, increasing enrolment rates of technical training programs (TVET), ensuring rigorous monitoring, and consolidating these training programs (which were previously administered by seven different ministries at different levels) would go a long way to developing skills Malaysians need. Currently, TVET enrolment is low compared to our regional peers. Evidence suggests that increasing the quality and access to vocational training is linked to lower rates of youth unemployment.

Third, a rethink is needed on how to aid those workers stuck in the low-paying jobs, with possible structured tax incentives for companies that offer training and advancement for employees to hire young workers who show promise. Efforts to provide a clearing house on job opportunities and market fairs can also be targeted to those most in need of higher paying jobs and greater job security.

Fourth, while there have been important reforms in encouraging student debt repayment, including incentives for repayment, Covid-19 may provide an opportunity to consider broader measures of student debt relief based on need and debt restructuring. This has occurred elsewhere after crises, notably the United States, with significant gains in financial security for young people – and shifts in political support. While questions of costs do rightly arise, it is also important to consider the costs of inaction and debilitating effects of inadequate measures for young people.

Finally, we need to appreciate that the social safety net in Malaysia is inadequate. The relief measures are tiny, compared to the scale of the economic downturn coming ahead, and the reality of being experienced now by those facing insecurity. Periods of economic crises make great opportunities for governments to invest in deepening and expanding social safety nets. We may need more thoughtful consideration of what measures are needed – beyond one-off cash relief – as money is likely only part of any solution ahead.

Dreams Ahead

While we do not yet know the full extent and intensity of Covid-19 aftermath, at least one thing is certain: the Covid-19 crisis will not end once the MCO is lifted. Covid-19 will not be over until it is over everywhere, and the reported case numbers are only the tip of the surface of the ongoing socio-economic trauma that will ensue. There is a pressing need to think through recovery and how to strengthen resilience—and a crucial part of this is assuring the future of Malaysia—its youth. Among the many of lessons of Covid-19 is the importance of investing in the country’s greatest resource – its people.

We close the essay with the thoughts of a few young Malaysians, who shared their thoughts:

Ms. A: I have no job. I have so much credit card debt I could scream. I do not know what I will do next. It’s scary. In spite of everything, I know I need to keep my dream for a better future alive.

Mr. Mhd: I used to work two jobs to take care of my family. I have lost both of them. I am thinking of going into food delivery but worry this will endanger my family. I don’t know what’s worse – maybe bringing home the virus or having my kids go hungry.

Mr. K: I love Malaysia. It is my country. I love it so much. I wish it would love me back.

Copyright: Calvin Cheng and Bridget Welsh, 2020