By

Dr Juita Mohamad

Fellow

Economics, Trade & Regional Integration

juita.mohamad@isis.org.my

Calvin Cheng

Analyst

Economics, Trade & Regional Integration

calvin.ckw@isis.org.my

1.0 Introduction and background

T

he Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free trade agreement (FTA) was signed on 15 November 2020 at the 2020 ASEAN Summit. The RCEP trade agreement comprises 15 member countries: all 10 ASEAN member states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam), and 5 of ASEAN’s existing FTA partners (Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea).

RCEP negotiations was formally launched in November 2012 at the 21st ASEAN Summit, where the ASEAN+6 leaders endorsed the RCEP framework and agreed to begin negotiations the following year. In 2019, and after 28 rounds of negotiations, India opted out of the deal for the time being amidst domestic political pressures. The remaining 15 countries completed text-based agreements in November 2019, and proceeded to signing without India in 2020.

The RCEP will be the second mega-regional FTA to involve the Asia-Pacific region after the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Nonetheless, RCEP will only come into force after 9 signatory countries (minimum of 6 ASEAN, 3 non-ASEAN) have ratified the agreement—which may take more than a year.

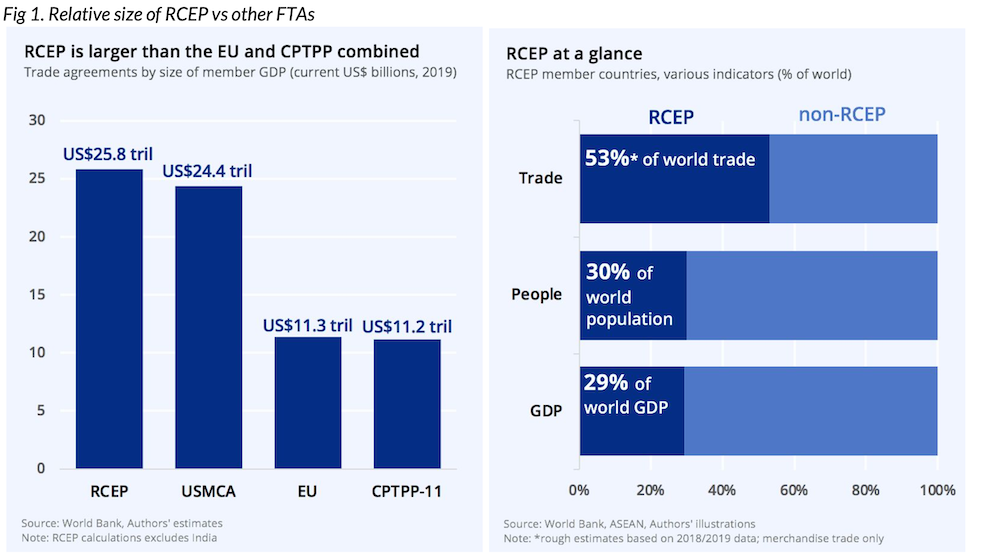

Altogether, the 15 RCEP member countries have an estimated GDP of US$25.8 trillion, accounting for about 29 percent of world GDP and making up 30 percent of the world’s population. This makes RCEP the largest trading bloc in the world by GDP size—even larger than the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and more than the size of European Union (see Fig 1) and CPTPP combined.

2.0 RCEP comparisons with CPTPP

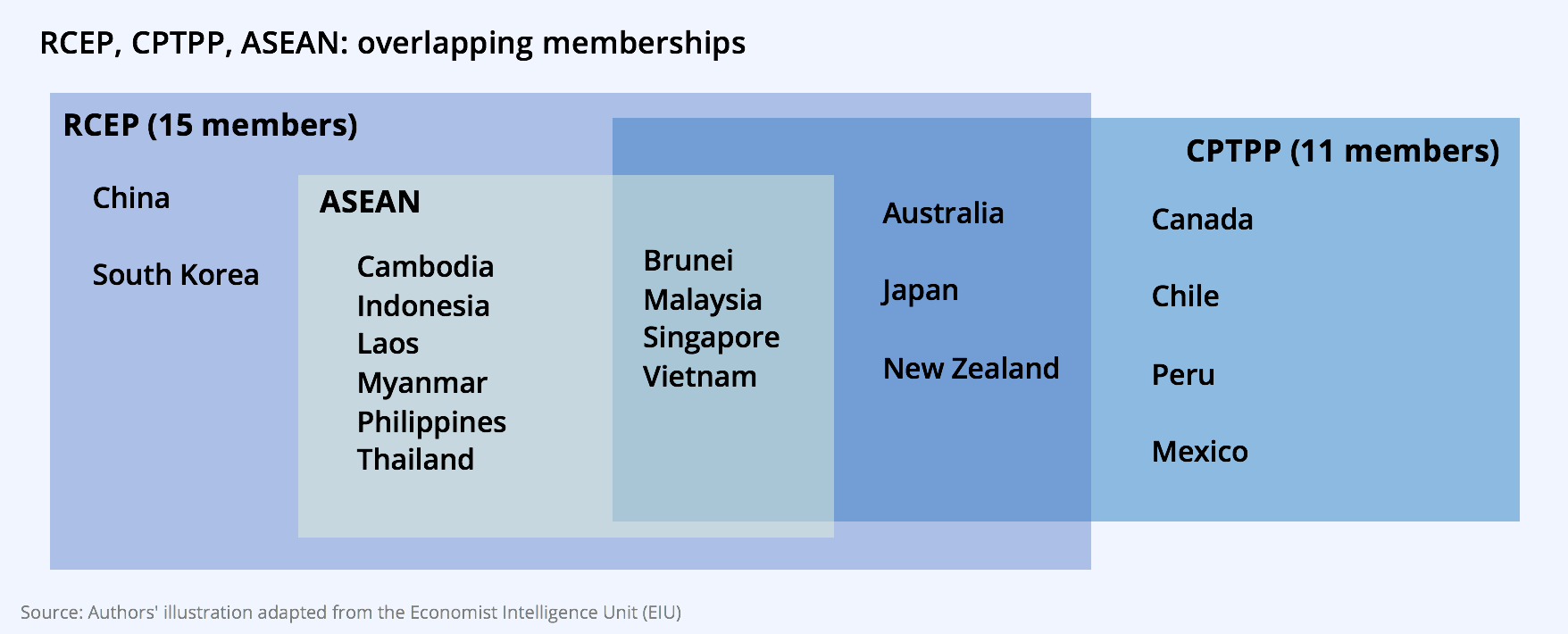

RCEP and CPTPP are both mega-regional FTAs involving the Asia-Pacific region, and there are large overlaps in membership between the two trade agreements. A notable difference is that RCEP is ASEAN-centric, and thus includes least-developed countries like Laos and Cambodia—while the CPTPP involves mostly upper-middle and high income economies including North and South American countries like Canada, Mexico, Chile and Peru.

Fig. 2 Member countries of RCEP vs CPTPP

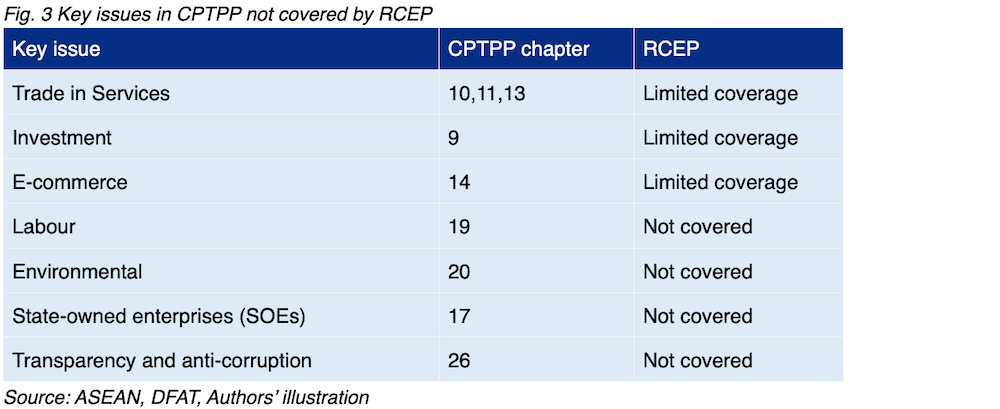

Given RCEP’s inclusion of lesser-developed economies, RCEP has always been less ambitious than the CPTPP in scope, depth, and speed of implementation of both tariff elimination as well as on behind-the-border issues like labour and environmental standards. Put differently, despite RCEP being twice as large as the CPTPP (see Fig.1)—RCEP is both wider and more shallow, while the CPTPP is narrower but deeper. Indeed, the CPTPP agreement consists of about 30 different chapters including chapters that aim to set a high-level standard on labour, the environment, state-owned enterprises, transparency and anti-corruption—while RCEP’s 20 chapters is heavily focused on harmonising barriers and procedures in regional trade, and setting “lowest common denominator” standards between member countries (see Fig. 3).

Nonetheless, given RCEP’s coverage of a large proportion of world GDP, trade and regional supply chains, it is expected to still provide tangible benefit to both RCEP economies as well as manufacturers and businesses in the region. As RCEP enters into force within the next two years, past experience with other existing ASEAN-related FTAs suggest that existing RCEP provisions will continue to be improved, upgraded, and deepened over time as RCEP economies continue to mature. In the future, CPTPP will represent a gold standard for a high-quality FTA that RCEP member countries may want to look towards.

3.0 RCEP, ASEAN centrality, and the role of China

Contrary to the speculation of ASEAN centrality being eroded by the presence of a major economy like China in such an agreement, RCEP is expected to further strengthen the fourth pillar of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint of committing ASEAN to be a region fully integrated into the global economy, in addition to it being (i) a single market and production base; (ii) a highly competitive economic region; as well as (iii) a region of equitable economic development.

Even before the pandemic, China has been one of ASEAN’s biggest trading partners. ASEAN and China have had strong trade relations for the past decade in part due to the establishment of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area. It is through this platform that trade liberalisation was implemented and investments between China and ASEAN flourished, strengthening economic and trade cooperation between China and ASEAN. Amid the backdrop of the pandemic, from January to August 2020, total trade between China and ASEAN increased by almost 4 percent compared to the same period last year, amounting to USD 416.5 billion and accounting for almost 15 percent of China’s total trade. In terms of investments, FDI outflows from China into ASEAN grew by about 53 percent.

In the next few years as the RCEP enters into force, trade between ASEAN and China is projected to increase in the medium term, as the RCEP serves as an upgrade to the existing FTA which only included areas of Trade in Goods, Trade in Services and Investments . With further cooperation in new areas such as Intellectual Property and E-Commerce between China and ASEAN, regional and global value chains in the region can be repaired and bolstered, and the Asia-Pacific may emerge once again as the engine of growth for the region and the world.

4.0 What RCEP means for trade reforms and its outlook

With the rise of protectionism and trade tensions in the past few years compounded by the spread of the pandemic, the finalisation and signing of RCEP was a strong signal by member countries to continue their commitment towards further regional integration and trade reforms in the Asia-Pacific region. Such an effort is very timely to offset the inward-looking policies adopted by certain countries in the region in the midst of curbing the spread of the virus.

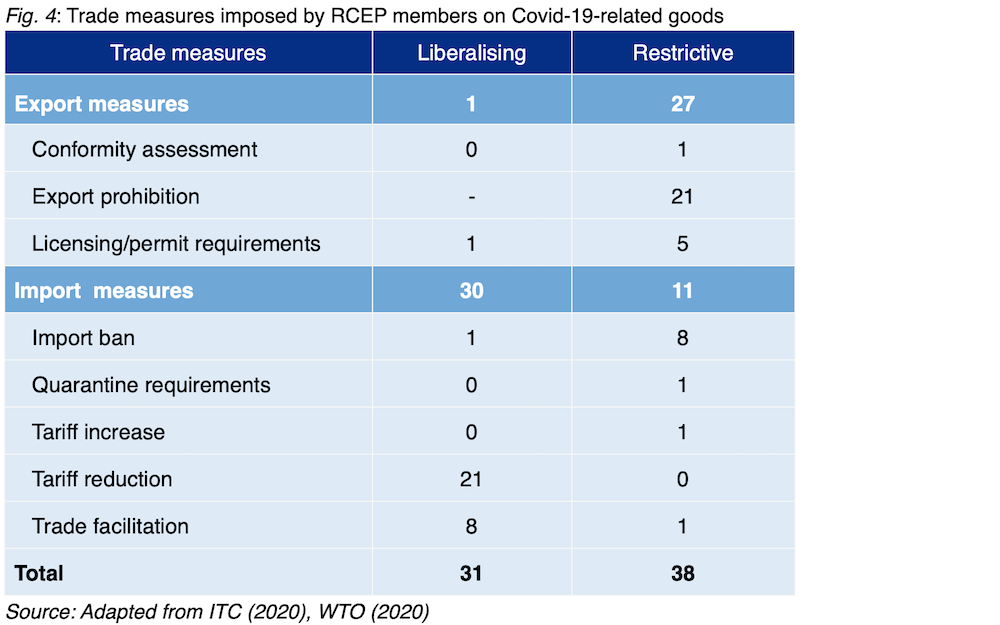

Yet, to move forward with further trade integration, lowering of tariffs is not enough. Non-tariff barriers need to be eliminated especially in the time of emergencies like we are facing now. It was unfortunate yet inevitable to observe that the spread of the COVID-19 virus across the globe has resulted in countries to close their borders and restrict physical economic activities, consequently disrupting the smooth flow of international trade. This was clear with the trade in PPE products among RCEP member countries due to the disruption of value chains of the essential products. As highlighted in the figure below various trade measures have been imposed by the RCEP members in response to the pandemic shock before the signing of the FTA last Sunday.

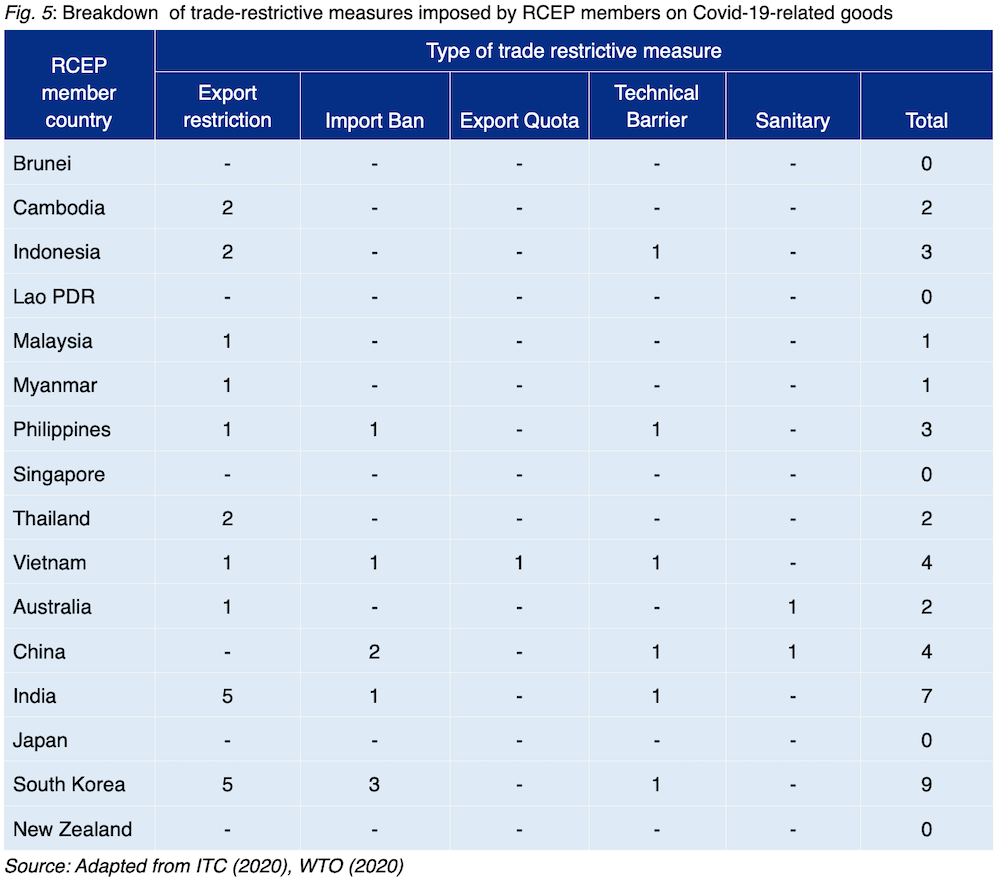

In a data set compiled by the International Trade Centre (ITC), from February to October 2020 a total of 66 trade measures both on exports and imports were implemented by RCEP countries during the initial months of the spread of the Covid-19 virus (see Fig. 4). To break it down further, Fig. 5 highlights the type of restrictive measures imposed by RCEP members related to Covid-19 goods such as medical equipment. Export prohibitions represented a total of 19 measures out of 35 was the main policy implemented by the RCEP governments. As of 15 October 2020, India and ROK introduced the highest number of export restrictions with five measures each. Both India and ROK also imposed the highest number of restrictive trade measures from February to October 2020 with a total of seven and nine measures respectively.

Although the restrictive trade measures are mainly imposed as temporary measures in response to the pandemic, the uncertainty of the Covid-19 resulted in the RCEP members to implement an unknown-termination-date trade measures. From February to October 2020, only nine restrictive trade measures were terminated out of 35, and eight of them were termination of export restrictions.

With the signing of the RCEP, it is hoped that further collaboration in fighting the spread of the virus would translate into the eradication of non-tariff measures (NTMs) and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for essential goods as well as non-essential goods. In the past we have seen that intra-ASEAN trade has not increased beyond the 35 percent threshold due to the existence of NTMs and NTBs in the backdrop of drastic reduction of tariffs over the years.

For RCEP members to be able to optimise this newly established trade bloc to intensify trade activities post pandemic, it is imperative that unjustified NTMs and NTBs are eliminated. If NTMs continue to rise while tariffs are cut, inter-trade activities will be stunted in the medium to long-term. Additionally if RCEP were to be upgraded in the future which it has room to do so, discipline chapters such as on the State-Owned Enterprises, Labour and Environment will only strengthen cooperation among members in areas not only limited to trade but also to the sustainability agenda championed by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

_______________

1ASEAN+6 includes all 10 ASEAN member states plus its 6 FTA partners: China, Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India

Reference list

- ASEAN Secretariat. 2020. “Summary of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement.” Available at: https://asean.org/storage/2020/11/Summary-of-the-RCEP-Agreement.pdf

- Jayant Menon and Anna Cassandra Melendez. 2019. “The upgraded ASEAN-People’s Republic of China Free Trade Agreement could matter, big time”. Asia Pathways, Asia Development Bank Institute. Available at: https://www.asiapathways-adbi.org/2019/08/the-upgraded-asean-prc-free-trade-agreement-could-matter-big-time/

- Julien Chaisse. 2020. “The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’s investment chapter: One step forward, two steps back?” Columbia Center on Sustainable Development FDI Perspectives No. 271. Available at: http://ccsi.columbia.edu/files/2018/10/No-271-Chaisse-FINAL.pdf

- New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. n.d. “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership text and resources”. Available at: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/cptpp/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership-text-and-resources/#chapters

- Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer, 2020. “East Asia Decouples from the United States: Trade War, COVID-19, and East Asia’s New Trade Blocs”. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 20-9. Available at: https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/wp20-9.pdf

- Takashi Terada. 2018. “RCEP Negotiations and the Implications for the United States”. Commentary from the Center for Innovation, Trade, and Strategy at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Available at: https://www.nbr.org/publication/rcep-negotiations-and-the-implications-for-the-united-states/

- Yoshifumi Fukunaga and Ikumo Isono. 2013. “Taking ASEAN+1 FTAs towards the RCEP: A Mapping Study”. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) Discussion Paper Series January 2013. Available at: https://www.eria.org/ERIA-DP-2013-02.pdf