On 18 January 2021, a week into the Movement Control Order for most states in Malaysia, the government announced the RM15 billion ‘Perlindungan Ekonomi dan Rakyat Malaysia’ (Permai) Assistance Package. Being the fourth major stimulus package since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, what does this Permai package include? How does it compare to previous stimulus packages and to other countries in the region? More importantly, could it go further?

The Permai economic assistance package

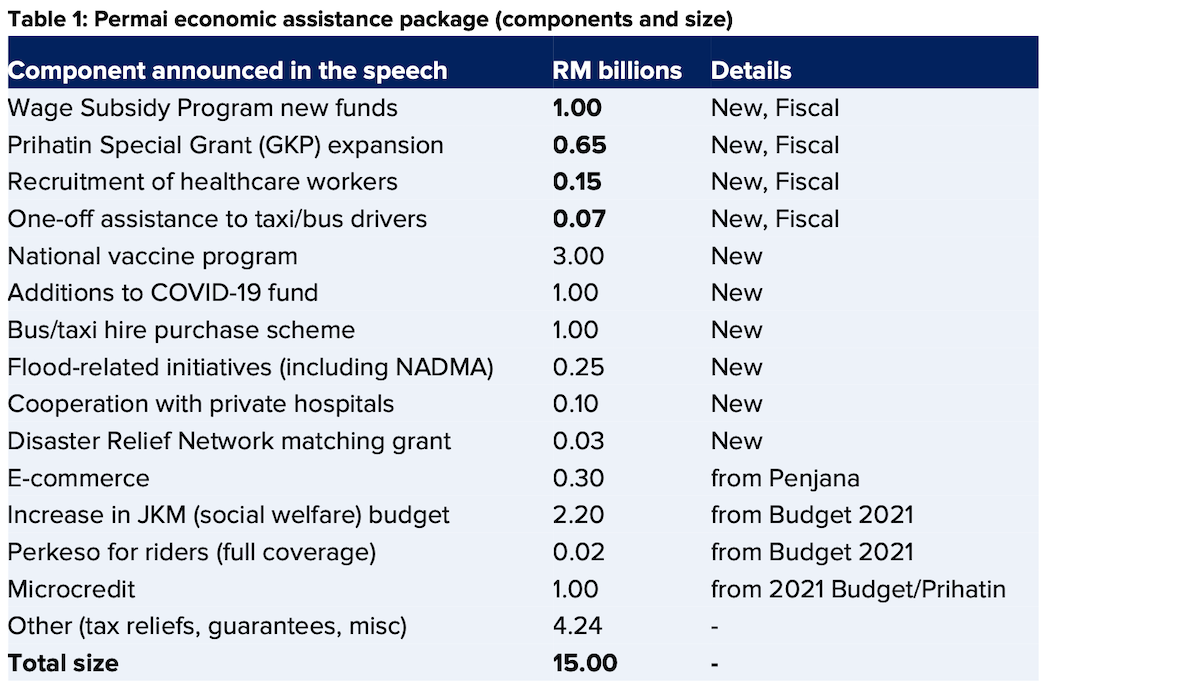

According to the announcement speech, the total Permai package size amounts to RM15 billion (about 1.0 percent of GDP). Key initiatives under Permai include a modest expansion of PERKESO’s Wage Subsidy program, allocations for a national vaccination program, and new funds for the Prihatin Special Grant (GKP) for microenterprises. However, similar to previous economic stimulus packages announced by the government, only a small proportion of the total package size actually involves new government spending (see Table 1).

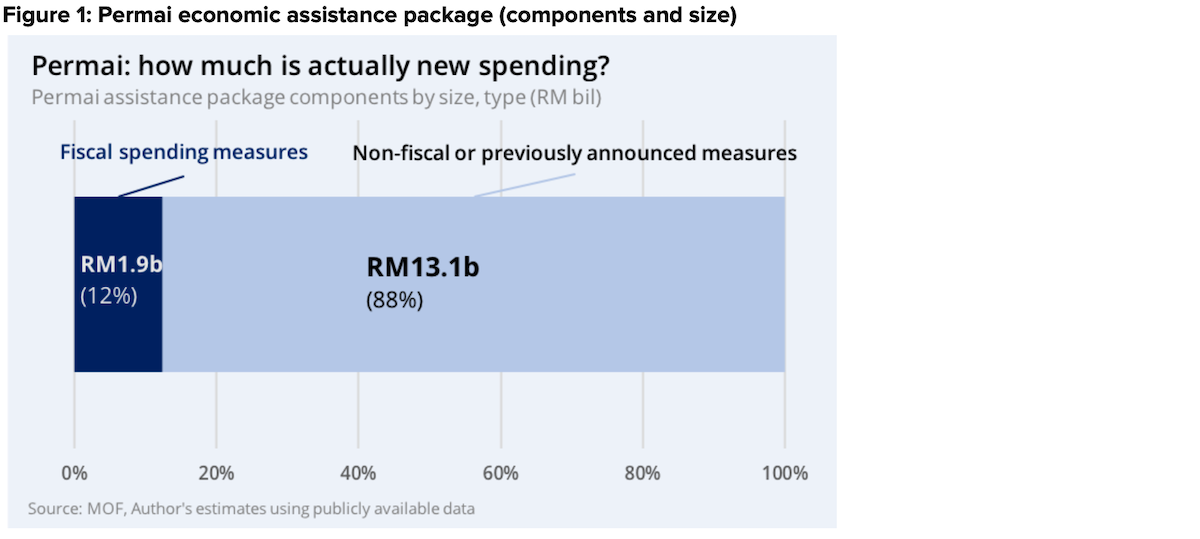

Overall, I estimate that only RM1.9 billion (12 percent of the total package size and about 0.1 percent of GDP) involves any new fiscal spending (Figure 1). That is, out of all the measures announced as part of the Permai economic assistance package, only four represent new fiscal spending. These include the new funds for the pre-existing Wage Subsidy Program; the grants for microenterprises (GKP); new funds for recruitment of healthcare workers; and the one-off cash assistance to taxi/bus/e-hailing drivers.

The remaining 88 percent mainly consist of non-fiscal measures like loan guarantees, moratoriums and quasi-fiscal loans, while a significant proportion seem to have been recycled from past initiatives announced either in the 2021 Budget or in older packages (Prihatin, Penjana). Notably, despite the declaration of emergency and the new (almost) nationwide movement controls, there are no new expansions of cash assistance to households. The Bantuan Prihatin Nasional 2.0 and Bantuan Prihatin Rakyat referenced in the speech are pre-existing cash assistance announced earlier in the Budget 2021 and the Prihatin packages respectively. Of course, complete details on the new PERMAI package, including exact allocation amounts are scant, and these figures are subject to change.

(Fiscal) Size matters

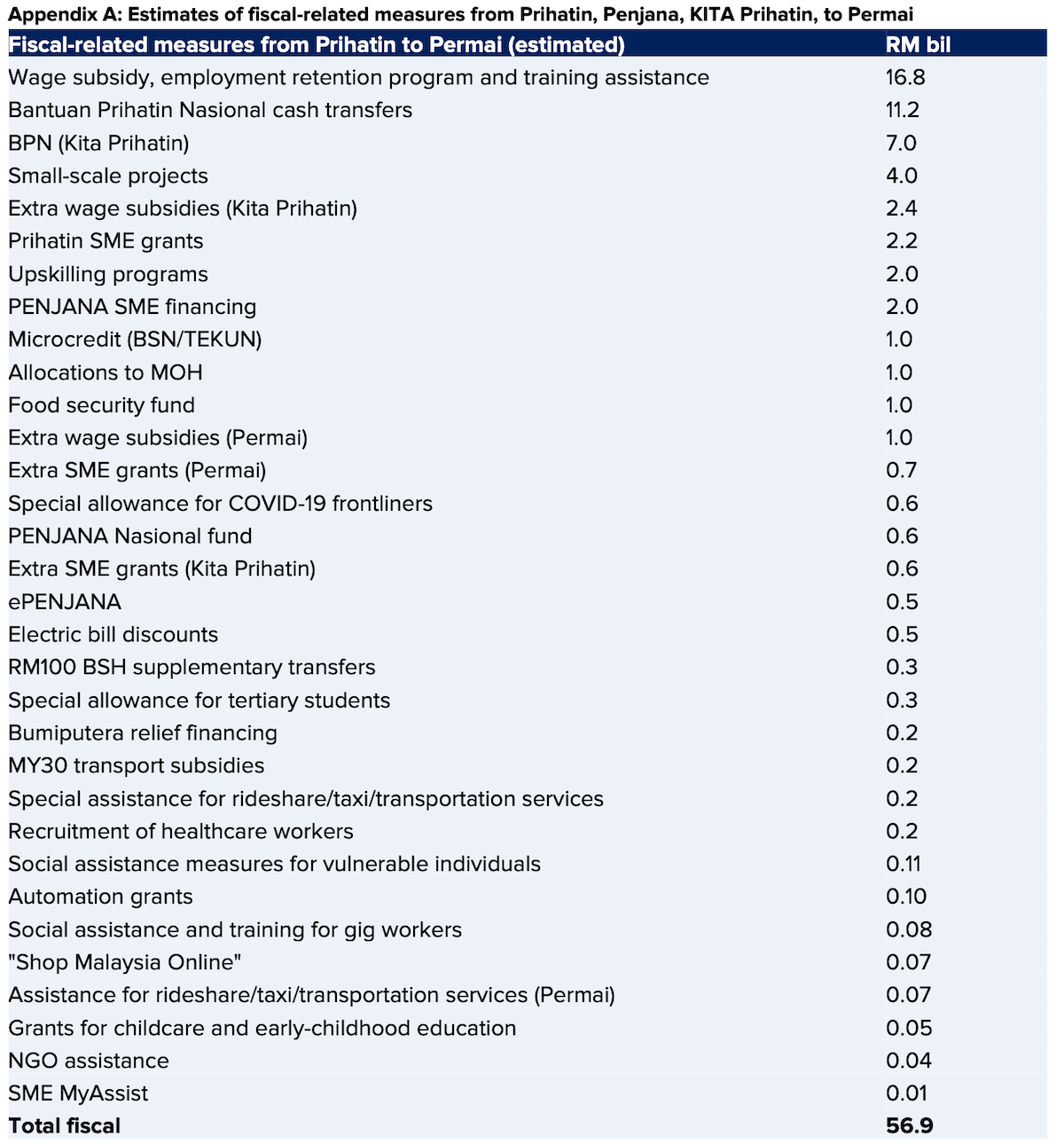

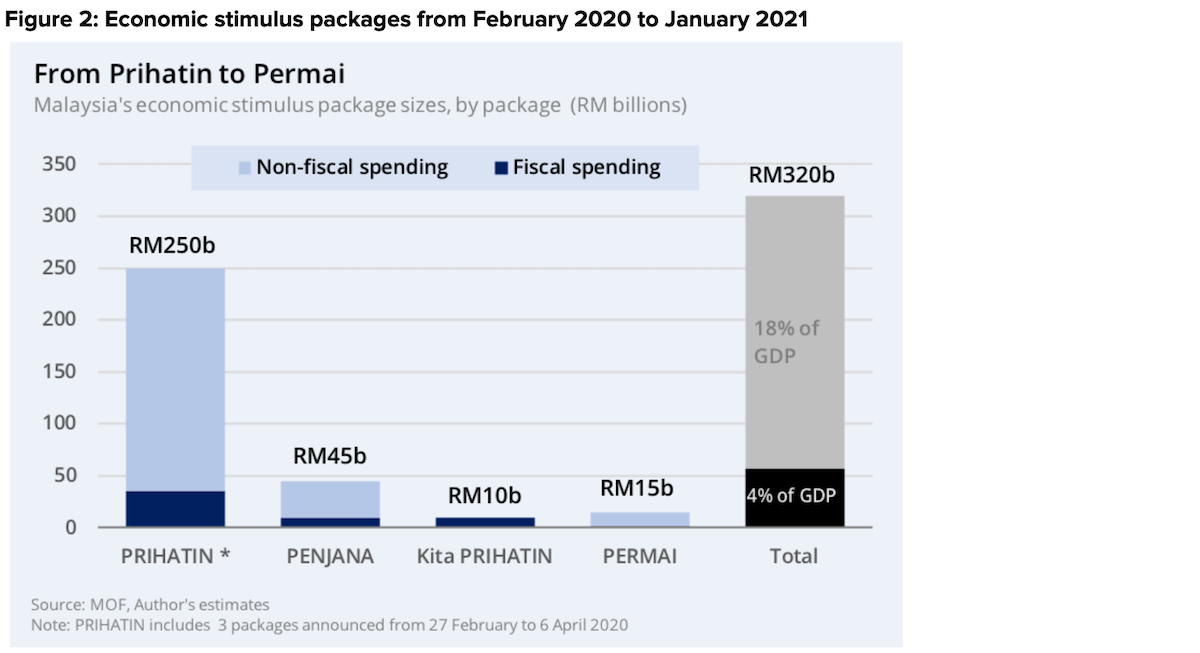

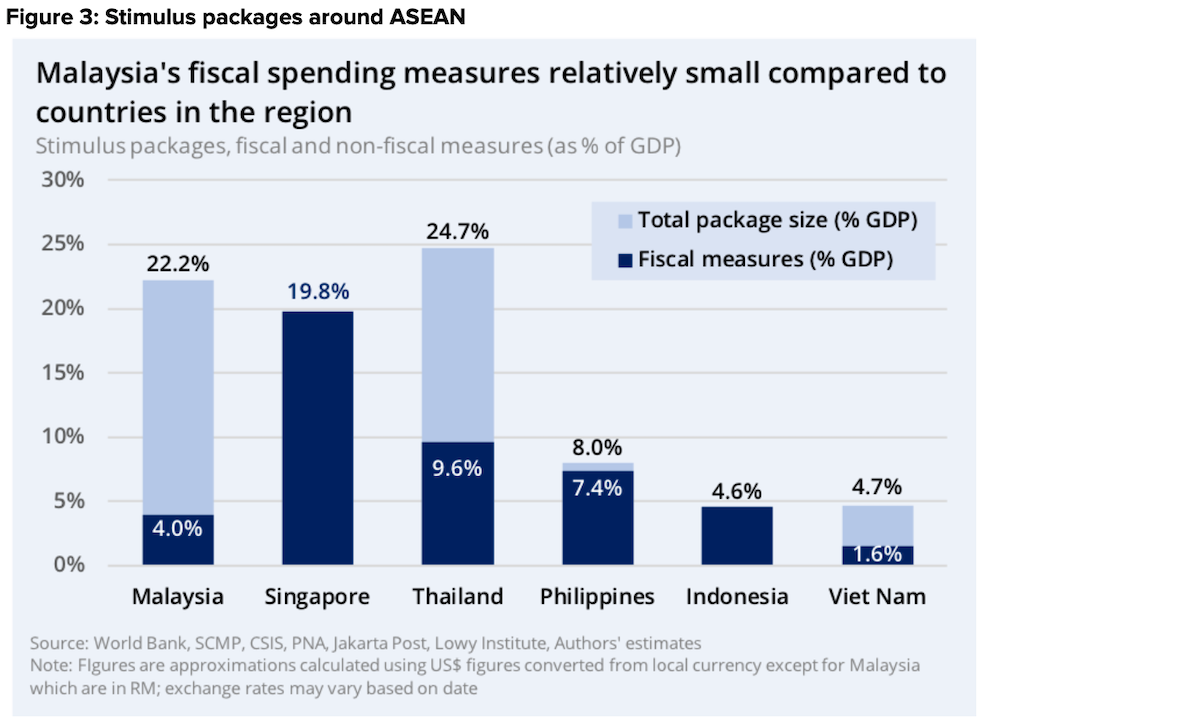

The announcement of the RM15 billion Permai economic assistance package bring the total amount of economic stimulus packages since the beginning of 2020—which includes Prihatin, Penjana, Kita Prihatin and Permai—to about RM320 billion, or about 22 percent of GDP. Again, despite this truly massive headline number, actual fiscal spending-related measures make up a fraction of that. My estimates suggest that only RM57 billion (4 percent of GDP) are fiscal spending measures.

Certainly, a large proportion of these fiscal measures have rightly been focused on supporting the welfare of households and workers (see Appendix A). Nonetheless, the measures announced under Permai may be largely inadequate to both combat the economic growth impacts of the resurgence in COVID-19 infection rates and the resultant movement restrictions across the country. This is especially so if the Permai package will be financed by entirely fund reallocations rather than through higher deficit spending, as was stated during its announcement. A quick look at stimulus efforts in the ASEAN region indicates that Malaysia’s COVID-19 economic response packages have among the lowest fiscal “bite”. Overall, I estimate that while Malaysia has the second-largest total package size amongst our ASEAN peers, it falls far below in terms of actual fiscal measures—second last only to Vietnam (see Figure 3). This is despite Malaysia facing some of the largest declines in GDP growth in the region over the past few quarters.

Truly, economic conditions are grim—even if this isn’t immediately apparent to many in the higher income bracket. Indeed, my past research has highlighted the largely unequal impacts of the pandemic on the marginalised lesser-educated workers, while tertiary-educated and more-affluent households have managed to remain relatively unscathed. Overall labour market conditions, far from ‘bouncing back’ as some optimists had predicted, have only continued to remain elevated. Large swathes of workers remain unemployed and unprotected by national unemployment insurance programs, continuing to be buffeted by increasingly uncertain economic conditions. Similarly, research on lower-income households during the pandemic indicates that measures of absolute poverty and deprivation have risen and will continue to rise even after movement restrictions are lifted.

More spending would lead to greater impacts for the long-run

As infection rates continue to soar, if movement restrictions are extended and economic data continues to confirm that a swift recovery is beyond reach—we would almost certainly need more forceful supplementary measures involving greater government spending.

As we have previously argued repeatedly over the past year: (read here and here), key initiatives would need to include a large (temporary) expansion and extension of EIS unemployment insurance. This would entail increasing the amount of time unemployed Malaysians can continue to receive benefits while searching for a new job, in addition to extending full coverage further to workers who do not meet the qualifying conditions. Alongside the support for workers, while the tweaks to the new Bantuan Prihatin Nasional 2.0 is encouraging, there is room to improve existing cash transfer programs and integrate cash support for childcare. Over the long-term, expanding infrastructure spending, particular in lesser-developed states, can present excellent opportunities to invest in future productivity while taking advantage of lower borrowing costs and supporting economic growth.

The moral imperative to support the welfare of the rakyat aside, as the adverse budgetary impacts of the coronavirus pandemic mounts, fears about fiscal deficits and debts will continue to rise—for good reason. Yet, pro-austerity apologists should note that fiscal deficits are ultimately measured as a percent of GDP. Attempts to reduce the fiscal deficit would mean little for fiscal space if growth eventually falters from inaction.