A version of this article was originally published on Malaysiakini

As a resurgence of COVID-19 cases and the return of strict movement restrictions in most states continue to dampen economic activity, the outlook for Malaysia’s economic growth is beginning to look increasingly grim. A confluence of factors, both external and domestic, threaten to derail the engines of economic recovery and dampen growth prospects in the medium-term. At the same time, if one looks far enough, there may be some cause for measured optimism on the horizon.

Storm clouds ahead

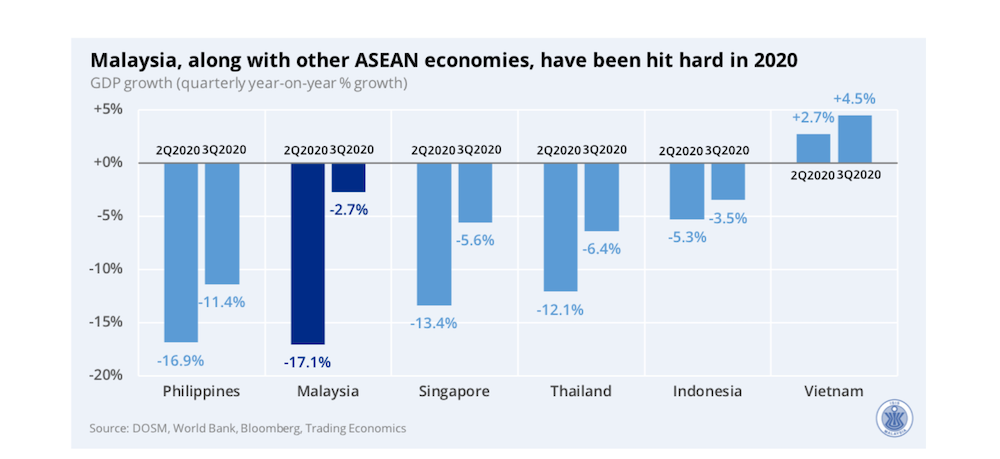

First, the Malaysian economy almost certainly already experienced the deepest recession in 2020 since the Asian Financial Crisis more than two decades ago. Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the first movement control restrictions (MCO1), Malaysia has recorded the sharpest contraction in GDP in 2Q2020 amongst the major ASEAN economies (-17.1 percent), though this rate of decline has attenuated in 3Q2020. Next week, the release of 4Q 2020 GDP is anticipated to show that the Malaysian economy has contracted by upwards of -5.5 percent for the full year of 2020. Similarly, measures of labour market conditions suggest that recovery is still a ways away—with the headline unemployment rate lingering at decade highs while marginalised workers remain increasingly pushed to the margins.

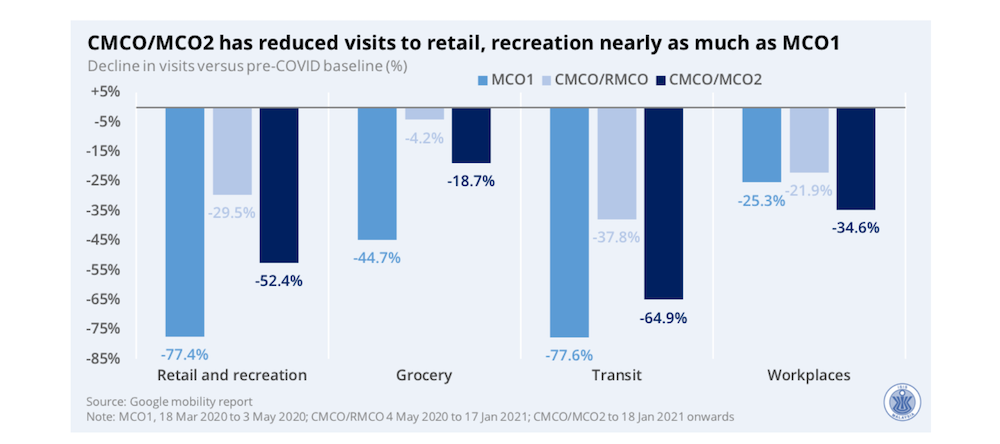

In an earlier publication, we observed that Malaysia’s economic recovery to pre-COVID levels will be sluggish—in sharp contrast with the swift recovery from the 2009 global financial crisis a decade ago. Back then, an upsurge in oil and electronics exports, along with rapid growth in foreign investment allowed GDP to recover to pre-crisis levels in less than a year. Today, tepid global energy prices and a large decline in foreign investment flows into Malaysia (-68 percent annual decline in 2020) make the prospects of a similar V-shaped recovery much more dubious. This is made worse by the recent return of stricter movement controls (CMCO2), which will continue to weigh on consumption and investment. Already, Google mobility data indicates that visits to locations—including retail and recreation and transit—have declined since the onset of MCO2/CMCO2 by almost as much as the first MCO1 in March 2020.

Secondly, forecasts of a brisk economic recovery in 2021 are underscored by a high degree of uncertainty. Indeed, many forecasts hinge on the assumption that the national vaccine plan will proceed smoothly. Yet, there are reasons to believe that at least a few snags are expected.

For one, the logistical and practical challenges are overwhelming. Healthcare experts suggest that nearly 80 percent of the population would have to be vaccinated before herd immunity can be achieved, particularly as new COVID-19 variants prove more infectious. As my colleague Harris Zainul notes, this, along with the fact that most vaccines are not available for people below 18 years of age may mean that roughly every single Malaysian of age needs to receive the vaccine. As such, even a small segment of the population resisting or rejecting the vaccine could lead to disastrous implications for herd immunity. Already, an Edge Markets straw poll hints that only about 5 out of 10 Malaysian respondents would choose to “immediately” agree to be vaccinated should a vaccine become available. There are other hurdles too. A national shortage of healthcare professionals (exacerbated by recent COVID-19 outbreaks in hospitals), along with the challenge of infrastructure adequacy in remote areas remain. Put together, these factors provide a convincing case that the path to herd immunity may be far more perilous than many realise.

Glimmers of hope

Yet, gloom and doom notwithstanding, there are some faint glimmers of hope.

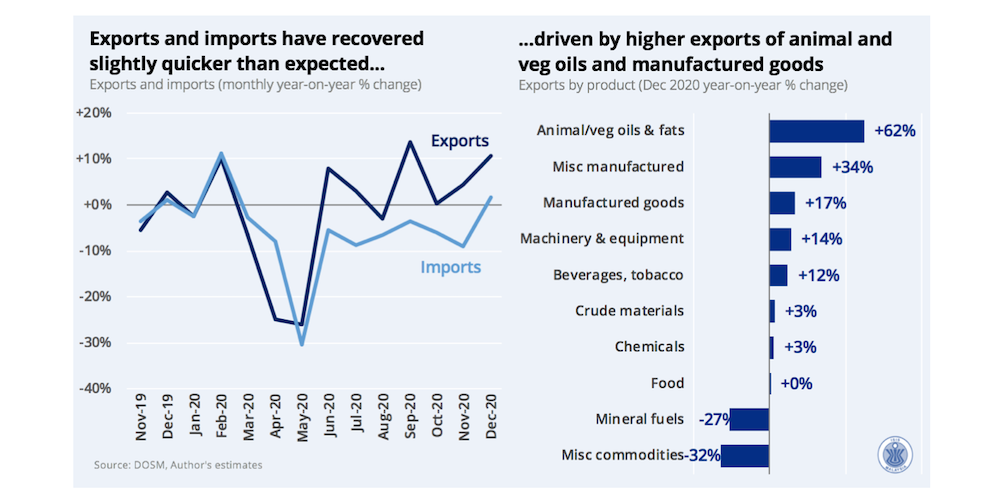

For one, Malaysia’s exports have recovered somewhat quicker-than-expected. Data for December 2020 show that exports grew by 10.8 percent year-on-year, allowing Malaysia’s export values to continue to exceed pre-crisis levels. This expansion in exports was driven by higher exports to China, Singapore and the United States—indicating that global demand may be healthier than expected, particularly as China’s economy continues to pick up pace. Looking ahead, if the world’s major economies continue to recover and grow and vaccine plans in their own countries progress, an expansion in demand may allow Malaysian exporters a brief respite.

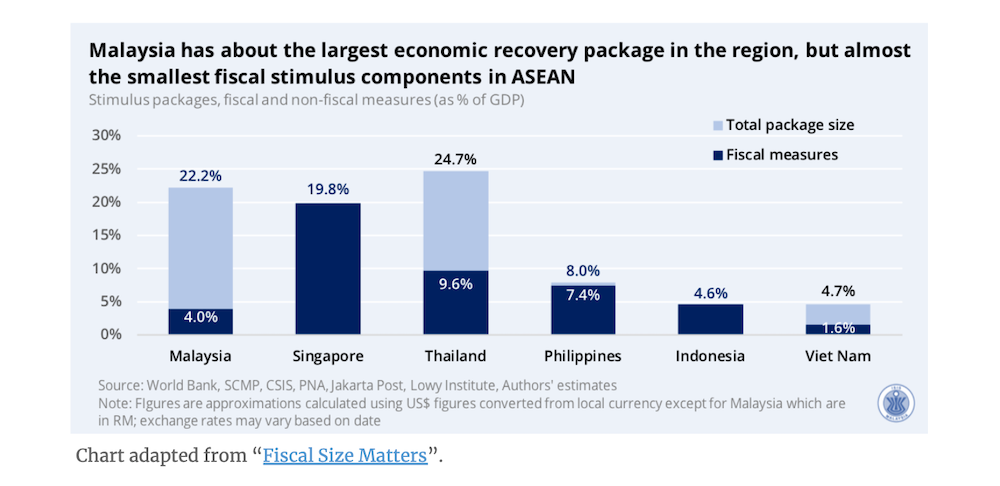

Besides, as case numbers continue to balloon and stricter measures are implemented, there is the hope that Malaysia’s fiscal policymakers will be cognizant of the need for further fiscal stimulus. As it stands, Malaysia’s fiscal-related measures (including Prihatin, Penjana and Permai) are amongst the lowest in the major ASEAN economies—despite the colossal total package size. Here, targeted expansions of Malaysia’s existing social safety net programs—particularly unemployment insurance—and a more decisive expansion of infrastructure spending would do a world of good. A backdrop of still-low borrowing costs and still-low inflation and mounting evidence of rising inequalities between marginalised workers and households suggests that costs of inaction could rapidly outstrip the fiscal costs of additional spending.

Lastly, recent data along with a handful of new studies have suggested that there may be a quicker way for countries facing vaccine shortages to achieve some level of protection against spread of the infectious coronavirus: spreading the two doses of a single vaccine (the prime and booster) across two different recipients—potentially allowing countries to more quickly offer a smaller amount of protection across a larger subset of the population. If further research finds this strategy to be optimal, and if implemented well, this could carry outsize benefits to the Malaysian economy and Malaysians as a whole .

On the whole, the uncertainty surrounding Malaysia’s economy appears deeply asymmetric: downside risks loom on the horizon relative to the more modest collection of upside risks. In any case, we should also not lose sight of the myriad hazards that lie in wait beyond the pursuit of economic growth. After all, even when the Malaysian economy manages to regain its footing and rebound past pre-crisis levels, the scars of the pandemic will linger for years to come.