by Ida Lim and Keertan Ayamany, 15 Apr 2021

KUALA LUMPUR, April 15 — Low earnings for Malaysian fresh graduates was a long-standing issue due to the lack of skilled and high-paying jobs in the country and not caused entirely by the Covid-19 pandemic, said analysts.

They disagreed with the government’s assertion that the growing proportion of graduates in the bottom RM1,001 to RM1,500 pay tier was solely a result of the economic disruptions that accompanied the pandemic.

The Ministry of Higher Education’s annual survey data as compiled by Malay Mail shows that a minimum of 10 per cent of fresh graduates with degrees have been earning between RM1,001 to RM1,500 for at least the past 10 years.

In 2020, the proportion of Malaysian graduates with degrees earning in the bracket hit a decade-high of 22.3 per cent. This was also the year when it became the biggest category, compared to other years including 2019 when the biggest category was RM2,001 to RM2,500 at 18.7 per cent.

Here’s what researchers told Malay Mail on why a higher number of Malaysian graduates are earning such low monthly income, and how it could be improved:

Seniority disadvantages young workers

Calvin Cheng, analyst in the economics programme at the Institute of Strategic & International Studies (Isis) Malaysia, agreed the rise in Malaysian graduates earning in the lowest bracket is likely largely “cyclical” or “transitory” and linked to reduction in work hours and economic shocks from the Covid-19 pandemic.

“However, while this effect may be mostly transitory, the whole reason why young workers tend to be most affected by the crisis in the first place is due to underlying inequalities,” he said.

Explaining why the passing impact of the Covid-19 crisis was more severe for younger workers, Cheng said this was due to deep-rooted structures that inevitably accorded more job protections with seniority.

“For one, young workers in general are usually the first ones to be let go (or face reduction in hours) during a downturn and the last ones to be employed when conditions improve (last in, first out).

“Also, young workers are far more likely to be in precarious jobs and persistently face higher rates of unemployment vs. older workers,” he said.

In the Department of Statistics Malaysia’s (DOSM) Labour Force Survey Report for the fourth quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate for 15- to 25-year-olds was 12.7 per cent or over two-and-half times the national average of 4.8 per cent.

“Narratives that push views that Malaysian graduates need to be ‘grateful’ or should not be ‘picky’ or narratives that seek to blame negative labour market effects on workers themselves — obscure both the seriously unequal and devastating impacts of the Covid crisis on youth as well as the larger structural context,” Cheng added.

Underemployed: Lower pay from fewer hours

Khazanah Research Institute’s (KRI) research associate Mohd Amirul Rafiq Abu Rahim also agreed that Covid-19 was partly why the biggest income group for graduates with degrees fell from the RM2,001 to RM2,500 bracket in 2019 (18.7 per cent) to RM1,001 to RM1,500 tier in 2020 (22.3 per cent).

However, he argued that this was exacerbated due to other structural issues such as youth underemployment in 2020, citing a recent KRI study based on DOSM data that found that 5.8 per cent of workers between the ages of 15 and 24 were underemployed by the end of 2020.

“At a minimum wage of RM1,200 per month or RM5.77 per hour, an underemployed worker who worked 30 hours per week could earn about RM173.10 per week or RM692.40 per month.

“It could be that the lower wages figure in 2020 is associated with the higher incidence of underemployment among the younger workers,” said Amirul Rafiq.

Noting that the KRI study attributed this trend to the restrictions on business activities during the movement control order (MCO) in the first half of 2020, Amirul Rafiq noted that more young workers remain underemployed even after the MCO was relaxed, as compared to older workers who were reabsorbed into full-time employment at a higher rate.

DOSM defines time-related underemployment as those who were employed for under 30 hours per week due to the nature of their work or because of insufficient work, and were able and willing to accept additional hours of work.

In other words, they are involuntarily given only fewer than 30 hours of work per week, when they are actually able to work more hours if required or given the opportunity to do so.

Cheng said his research suggested young graduates, mainly diploma or degree holders, also faced higher risk of underemployment, such as a reduction in working hours, compared to older workers.

“My estimates using recent labour force survey data suggest that the number of young workers, aged 15 to 24, who are working less than 30 hours a week has increased by a whopping 186 per cent from 2019 to 2020,” he said.

Cheng said his estimates of quarterly labour force data in Malaysia indicate that the quarterly average of young workers aged 15 to 24 working fewer than 30 hours per week was 126,800 people in 2020 versus a quarterly average of 44,350 in 2019, or nearly three times higher.

As for time-related underemployment, Cheng said his same estimates indicate that there was a similar increase in terms of percentage (185 per cent) for the quarterly average of young workers aged 15 to 24 in time-related underemployment in 2020 (378,200 workers) as compared to in 2019 (132,900), which represents an increase of 245,300 workers in quarterly average between those two years.

Graduates > Skilled jobs

Amirul Rafiq said the problem was systemic as most firms in Malaysia did not rely on skilled labour, which meant there was a shortage of skilled work compared to the number of graduates in or entering the job market.

While there are jobs with higher value-added and higher wages per worker such as in professional services and ICT, he said these sectors only employ about seven per cent of the workforce and tend to be concentrated in richer states such as Selangor, Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya.

A third of jobs in Malaysia are focused in the service sector that typically do not have high value-added and wages per worker, with jobs in wholesale and retail, accommodation and food and beverage, as well as administrative and support services having wage levels of between RM2,081 and RM2,363 only, as compared to national levels of RM3,224.

Amirul Rafiq said these economic activities tend to disproportionately employ younger workers, which meant they are more exposed to employment in lower-wage economic activities, further noting that such data indicates that Malaysia’s economic activities are labour-intensive and skewed towards low and semi-skilled workers.

“Again, this is also reflected in our SWTS study, where 95 per cent of our young respondents with unskilled jobs and 50 per cent of those with low-skilled manual jobs were found to be over-educated,” he said, referring to KRI’s 2018 study on a School-to-Work Transition Survey of young Malaysians.

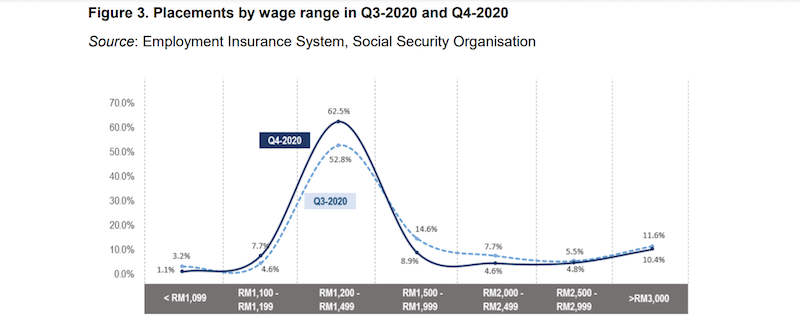

The human resources minister recently said that the Social Security Organisation’s (Socso) Employment Insurance System (EIS) data showed that 52.8 per cent and 62.5 per cent of workers hired in the third and fourth quarter of 2020 received wages in the RM1,200 to RM1,499 category, due to reasons such as jobseekers opting to temporarily take up non-graduate jobs rather than remain unemployed amid a shortage of vacancies for graduate jobs.

Low starting pay compounded by stagnant wage growth

Amirul Rafiq said another factor was pre-existing wage levels, noting KRI’s November 2020 report which found real median monthly wages nationally to have risen by 3.3 per cent per year from RM1,823 in 2010 to RM2,442 in 2019, and with annual wage growth of diploma and degree holders being very close to inflation growth, while wage growth for workers under the age of 30 were among the lowest when compared to other age categories.

Amirul Rafiq said a 2018 KRI report had in a pre-pandemic survey found that the average minimum salary that employers were willing to offer or pay to tertiary-educated workers was RM1,700, which is lower than the minimum salary that tertiary-educated job seekers (RM1,955) and students in tertiary education institutions (RM2,435) were willing to accept for a job.

“This finding also contradicts claims made by various sources that fresh graduates are demanding and expecting unrealistic starting salary.

“All these trends could indicate that younger workers, even those with tertiary education qualification, seem to experience limited wage growth and starting salaries compared to other workers, even before the crisis began,” he said.

Muhammed Abdul Khalid, research fellow at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia’s (UKM) Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), said it was “shameful and irresponsible” for ministers to claim graduates should be grateful to even have jobs amid the Covid-19 pandemic when the pay was so low.

Muhammed went on to say that it was incorrect to blame the situation on the Covid-19 pandemic, as structural issues such as underemployment and low wages predated it.

“There is a serious issue of underemployment among graduates. During the 2010-2019 period, 73 out of 100 jobs created were semi and low skilled jobs. In 2019, only 28 per cent of total workers are skilled workers, almost unchanged in the past one decade. At the same time, the number of graduates has been increasing.

“Graduates’ salaries have not increased. Adjusting for inflation, real starting monthly salaries for most fresh graduates has declined since 2010,” the economist told Malay Mail.

In Bank Negara Malaysia’s (BNM) 2018 annual report, the central bank cited the Malaysian Employers Federation’s 2010 and 2018 salary surveys when saying that data showed the starting monthly salaries for fresh graduates had declined since 2010, after adjusting for inflation.

The BNM estimates showed that a fresh graduates with a diploma earned a real salary of RM1,376 in 2018 as compared to a higher RM1,458 in 2010 for executive roles, while the same was observed for graduates with a basic degree (RM1,993 in 2010 versus RM1,983 in 2018) or an honours degree (RM2,228 in 2010 versus RM2,169 in 2018) or a Masters’ degree (RM2,923 in 2010 versus RM2,707 in 2018).

In the latest data from the DOSM titled Graduates Statistics 2019 and released on July 16, 2020, the median monthly salaries of employed graduates aged 24 and younger in Malaysia was at RM1,800 in both the years 2016 and 2017, and estimated to be RM2,112 in 2018 and with preliminary figures also indicating it would remain RM2,112 in 2019.

As for mean monthly wages, the same set of DOSM data for employed graduates aged 24 and below showed that it was RM1,978 in 2016, RM2,146 in 2017, RM2,320 in 2018 and RM2,378 in 2019.

Based on the DOSM estimates of a median salary of RM2,112 for graduates aged 24 and below in both 2018 and 2019, Muhammed said this indicates stagnant wages.

“Adjusting for inflation, the wages should be higher, not stagnant. It means in real terms; the salary is actually lower now compared to a few years ago. This amount is clearly not enough for a worker to lead a meaningful life.

“According to a study by EPF, a single person without a car who lives in Klang valley needs at least around RM1,900 per month to survive. If the person has a car, he or she needs at least RM2,500 per month,” he said.

In March 2019, the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) had together with the University of Malaya’s Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC) launched an expenditure guide to provide estimates of the minimum monthly spending in 2019 that would allow Malaysian individuals and households in the Klang Valley to have a “reasonable standard of living”.

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) had in a March 2018 paper also gave its provisional estimates — which are subject to revision — for monthly “living wage” levels or wage levels required for a “minimum acceptable living standard” in 2016 in national capital Kuala Lumpur, namely RM2,700 for a single adult, RM4,500 for a couple, RM6,500 for a couple with two children.

Cheng said the lack of long-term wage growth was a major problem as workers under 29 only saw their annual income growth outpace inflation in two out of 10 years until 2019.

“Even that is an optimistic estimate as CPI is an imperfect gauge for the true level of cost of living,” he said, referring to the Consumer Price Index.

Cheng said the “persistently ‘low’ wages” and low wage growth for graduates over the years are a result of structural factors including mismatches between labour supply and demand.

He added that there is a need to empower workers and shift bargaining power from employers to workers through stronger labour market institutions (including minimum wages, worker protection legislation, unemployment insurance), collective bargaining mechanisms, stronger implementation and enforcement of labour laws.

Recovery? The answer is in jobs and reducing underemployment

On whether the situation for young workers would improve from 2020, Cheng said that the real question is when the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will truly subside.

Cheng said his past research showed that a recovery in GDP growth back to pre-crisis levels would not mean that the economic effects have subsided, noting that it will “take years” for a true recovery in the labour market, especially for workers groups that are most heavily affected such as those who are younger or female or lesser-educated.

“Nonetheless, as labour market conditions gradually recover in tandem with higher growth, and as demand picks up, time-related underemployment is likely to decrease — and this would eventually show up in the data as a higher percentage of graduates in higher income categories beyond RM1,500,” he said.

“Yet I anticipate that a labour market recovery — even on aggregate in terms of the unemployment rate — will be gradual. Hundreds of thousands of workers have exited the labour force entirely in the past year and as such are not counted in unemployment figures.

“As such, there is a large stock of potential workers sitting outside the sidelines, and a recovery would need to be sustained enough that these people outside the labour force will gradually start to re-enter the labour force and seek employment,” he added.

Muhammed similarly said recovery in the labour market “will take time”, and stressed on making more jobs available instead of focusing on the GDP as a measure of economic growth.

“If you look at the global financial crisis in 2008, the salary of graduates stagnated for five years before it started to increase. And clearly the Covid-19 pandemic crisis is worse than the financial crisis and recovery may be longer. As it stands, the labour conditions at the moment is the worst ever in the past 30 years.

“Focusing on GDP as a sign that the economy is growing is pointless, one should focus on job creation. We can have an increase in GDP, but unemployment or poverty and inequality can still go up,” he said.

Amirul Rafiq also pointed to the need to ensure enough jobs that match the skills and qualifications of Malaysian graduates, having also noted that studies show fresh graduates who graduate in a time of recession or crisis would damage their employment prospects, income and life satisfaction.

“Underemployment is also associated with more structural issues in the labour market, beyond Covid-19, and we should not simply assume that gaps in the labour market will immediately decline after the crisis,” he said.

He pointed to skill-related underemployment (SRU) where workers with tertiary education qualification work in semi-skilled and low-skilled jobs, instead of the higher-paying skilled jobs. DOSM meanwhile defines skill-related underemployment as those who want to change their current employment situation in order to fully utilise their occupational skills.

“The SRU in Malaysia has been growing from 2017 (8 per cent) to 2020 (12 per cent) and also much higher among younger workers (under 35 years old), compared to older workers (above 35 years old), and it continued to rise during Covid-19,” he said, adding that the persistence of SRU could be explained by the nature of job demand before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“During the pandemic, and specifically, post-MCO when business activities resumed, overall private-sector job creation contracted. Only manufacturing reported new jobs created, but these jobs were semi-skilled and low-skilled jobs,” he said.

Amirul Rafiq acknowledged the government’s initiatives to cushion the blow caused by Covid-19 and to hire, upskill and retrain youths, including e-latih with free access to over 200 skills development courses and the Social Security Organisation’s (Socso) efforts to match jobseekers with work such as the MYFutureJobs portal and job fairs.

“But improvement on the quality of our labour supply must also be matched with meaningful attempts to create decent jobs throughout the country. This will require collaborative work between the government, private sector employers as well as youth looking for jobs,” he said.

* In Part I of this story yesterday that can be found here, Malay Mail explains how data showed that increasingly fresh graduates have been earning between RM1,001 and RM1,500 since at least 2010, with the proportion reaching its peak last year amid Covid-19

This article was first appeared on the Malay Mail on 15 April 2021