While many have been devastated by the sweeping impacts of the pandemic—others are redirecting travel budgets into increased spending on shopping, dining, and entertainment.

It is 3pm on a Tuesday at The Gardens, a high-end shopping mall in Kuala Lumpur and already, a small line is snaking around the entrance of Louis Vuitton. A few kilometres away in Bukit Bintang, another luxury mall, Pavilion, is enjoying similar foot traffic—with shoppers milling around the storefronts of retailers like Yves Saint Laurent and Pandora. In rich urban neighbourhoods across the Klang Valley, the sight of small crowds in and around luxury boutiques, jewellers, watch shops and upscale restaurants have become increasingly common.

By many measures, the COVID-19 crisis has been devastating. Malaysia’s GDP experienced its largest contraction in 2020 since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. The unemployment rate remains at levels last seen in the 1980s, with data indicating that nearly 780,000 Malaysian workers remain unemployed and hundreds of thousands more have exited the workforce entirely. As a UNICEF survey conducted after the first Movement Control Order (MCO) suggests, the pandemic has pushed many families into poverty, with one in two low-income households living in absolute poverty and more than a third struggling to buy enough food to feed their families.

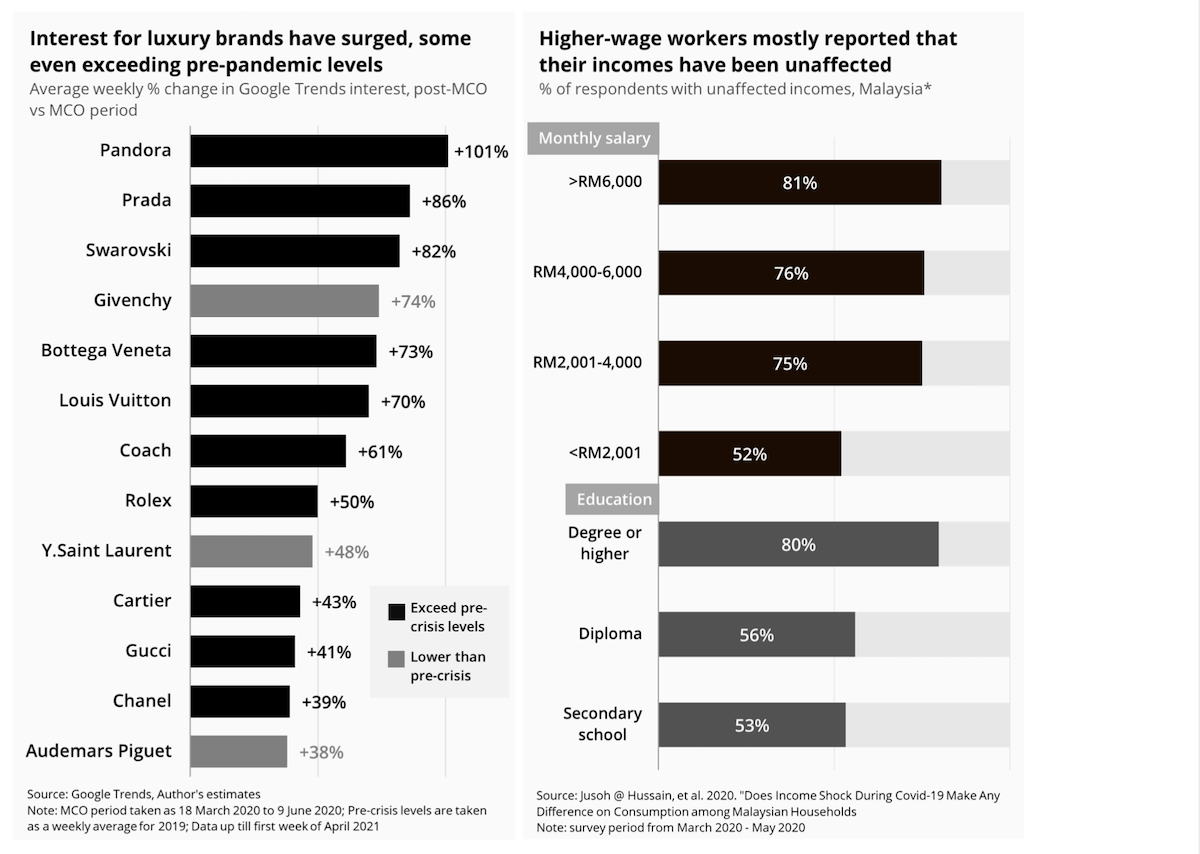

Yet, looking at many affluent urban communities and neighbourhoods in the Klang Valley reveals that a large swath of higher-income, white-collar, urban Malaysians have emerged from the pandemic mostly unscathed. As movement restrictions were relaxed and as virus fears ebbed, throngs of rich and upper-middle-income Malaysians have been returning to spend at the luxury boutiques and restaurants across the city. Google Trends data for Malaysia indicate that search interest in luxury brands have surged after an initial slump during the first MCO. Luxury fashion houses like Prada, Givenchy, and Louis Vuitton, along with high-end accessory retailers like Pandora, Swarovski and Rolex have all seen large gains in interest—surpassing even pre-pandemic levels (see chart below).

Government policy has helped too. The numerous tax exemptions that were unveiled as part of the government’s Penjana stimulus package have bolstered the automobile and real estate markets. Indeed, sales volumes for luxury cars have not fallen by much in 2020 despite months of lockdown and an economy battered by COVID-19. Mercedes-Benz Malaysia reported last September that demand has already exceeded pre-pandemic levels, while BMW Malaysia announced that it delivered more than 11,000 vehicles in 2020. Similarly, high-end real estate has hardly collapsed despite the closure of international borders. Just a few months ago, virtually every available unit in TRX Residences’ Tower A in Kuala Lumpur—a luxury residence where a small 474-square-foot unit listed for about one million ringgit—quickly sold out in a pre-sales phase.

These conflicting anecdotes may appear surreal and dissonant. Even as millions of Malaysians have been completely devastated by the pandemic, there are also many urban communities for whom COVID-19 appears to have been little more than a minor inconvenience. But why is this? What explains this deep divide between different communities facing the same crisis?

For one, the job impacts of the pandemic were tremendously unequal. Our research has shown that the employment of higher-wage, tertiary-educated, white-collar workers remained strong, as COVID-induced job losses were overwhelmingly concentrated in lower-wage, blue-collar jobs held mostly by lesser-educated, marginalised workers. Even at the peak of the MCO in Malaysia, surveys suggest that the incomes of an overwhelming majority of higher-wage, higher-educated workers were entirely unaffected—even as nearly one in two lower-wage, lower-educated workers reported significant income losses (see chart above). There is also evidence of geospatial disparities—with workers in wealthier urban centres like Kuala Lumpur, Selangor and Penang more likely to have seen their incomes remaining intact while conversely, workers in states like Sabah, Kelantan and Perlis reported far higher rates of income declines.

Of course, this goes beyond incomes. Richer Malaysians are far more likely to own housing and financial assets, and as such have mostly managed to see gains—or at the very least sustained only small declines—in their overall wealth. Unlike in past recessions which were precipitated by financial crises, this time, global equities have managed to rebound quickly to record highs while even the FBM KLCI has managed to recoup most of its losses from the previous year. At the same time, median house prices still grew by about 2 percent last year, while the composite house price index managed a marginal 0.6 percent growth. For the most part, capital-owning Malaysians have only gotten richer over the year, mirroring global trends amongst the world’s top 1 percent. As a recent Oxfam report notes: it took a mere nine months for the world’s top 1,000 billionaires to recover to pre-pandemic levels of wealth, but a similar recovery for the world’s poorest could take up to a decade.

In short, the COVID-19 crisis has been uniquely unequal in ways that the 2009 Global Financial Crisis and the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis never were. These uneven effects on incomes and wealth reveal how and why different communities in the same country can experience the same recession differently. Indeed, many have been completely ravaged by the economic, health and psychosocial impacts of the crisis. But if the lines outside Louis Vuitton are anything to go by, there are also pockets of wealthier, urban Malaysians eager to redirect former travel budgets into increased spending on shopping, dining, and entertainment. In the early days of the pandemic, health authorities repeated the usual platitudes about how “we are all in this together” in the fight against COVID-19. Yet, a year later, this deep disconnect between the have and have-nots exposes an uncomfortable truth beneath this rhetoric: perhaps we were never really in this together to begin with.

A shorter version of this article was first published via the New Straits Times here