As nations mull reopening borders, they must consider how to balance travel and public health interests.

PUBLIC conversations last week had, among others, centred on the topic of vaccine passports. Namely, whether Malaysians who received the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccines as part of the National Covid-19 Immunisation Programme (NCIP) would be able to travel to European Union (EU) member states. This follows the EU’s implementation of what is formally called the “EU digital covid certificate”, which is a vaccine passport by another name.

Since then, the EU delegation to Malaysia has clarified that it is not compulsory for travellers to its member states to have these digital certificates and is instead, a practical tool to facilitate travel. The delegation also emphasised that EU member states are free to recognise any other vaccines outside of those currently recognised by the bloc – with at least five member states already recognising the Covishield vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India.

While public conversations on vaccine passports have since tempered with the clarification, and perhaps since politicking has once again reared its ugly head and dominate public discourse – the question of travelling in a post-Covid-19 world is still far from settled.

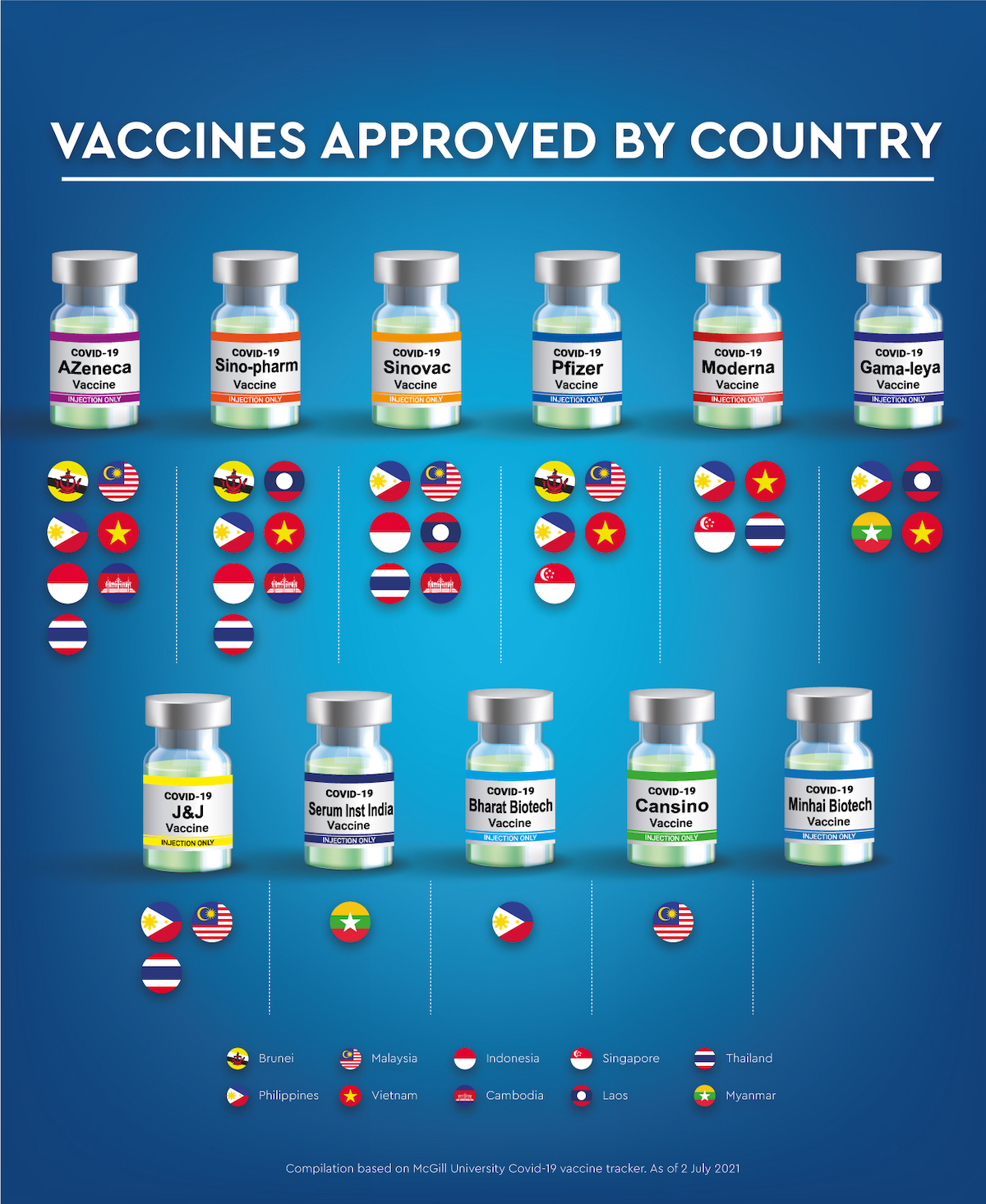

In our own region, Asean, there is no one single vaccine approved by every member state. In fact, even if we were to treat the Covishield vaccine similarly to an AstraZeneca vaccine, only 80% of member states have approved it for domestic use. Other vaccines, namely the ones produced by Sinopharm and Sinovac are recognised by seven Asean member states (table below).

This highlights the quandary of basing immunity status on the common recognition of vaccines. Besides that, and looking at the long term, would it not make more sense for travellers to be allowed to travel without lengthy and oftentimes costly quarantines based on their immunity levels rather than what vaccine they had received?

This idea, while relatively newer, would allow countries to side-step questions about vaccine efficacy – and perhaps to an extension, vaccine nationalism – and consider the most important factor, which is to allow travel in a manner that is as safe as possible.

With most countries’ Covid-19 “exit plan” hinging on vaccinating as many people as possible, nothing, and not even dreams of travelling to faraway exotic lands, should be taking anything away from this. The last thing we want is for people to be holding off on their vaccination appointments because they prefer receiving a “more recognised” vaccine.

The fact of the matter is that with Covid-19 resulting in more deaths this year than the entire 2020, despite the existence of various safe and efficacious vaccines – countries are approving a variety of vaccines. These decisions are based on the primary considerations of safety and efficacy, and the secondary considerations of supply and delivery dates to ensure that their entire populations are able to vaccinate as quickly as possible.

That said, as we inch closer to a post-Covid-19 world, questions of balancing between the twin objectives of resuming international travel and public health interests must be considered. To that end, we must ensure that it is as equitable as possible, and does not inadvertently result in widening inequality, or worse, leading to people delaying vaccination dates.

A low-cost carrier’s tagline is “now everyone can fly” and in a post-Covid-19 world, we should ensure that it comes with as few disclaimers as possible.