Calvin Cheng was quoted in Nikkei Asia.

by P Prem Kumar and CK Tan, 15 February 2022

KUALA LUMPUR/SHANGHAI — When engineers and mechanics at Malaysia’s largest car manufacturer need a breather, they head to the “dojo.”

The Japanese word, which typically describes a hall for practicing martial arts, lends an air of gravitas to what is essentially a break room for workers at Perodua, officially Perusahaan Otomobil Kedua. Perodua makes liberal use of the term at its employee training center, too. There’s a “sales dojo,” a “parts dojo,” a “service dojo” — each focusing on different skills, with a nod to the influence of Japan and part-owner Daihatsu.

The origins of that influence can be traced to February 1982, when then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad introduced his “Look East Policy.” At a time when developing countries turned to the West for role models, Mahathir focused on a rising South Korea and, especially, Japan.

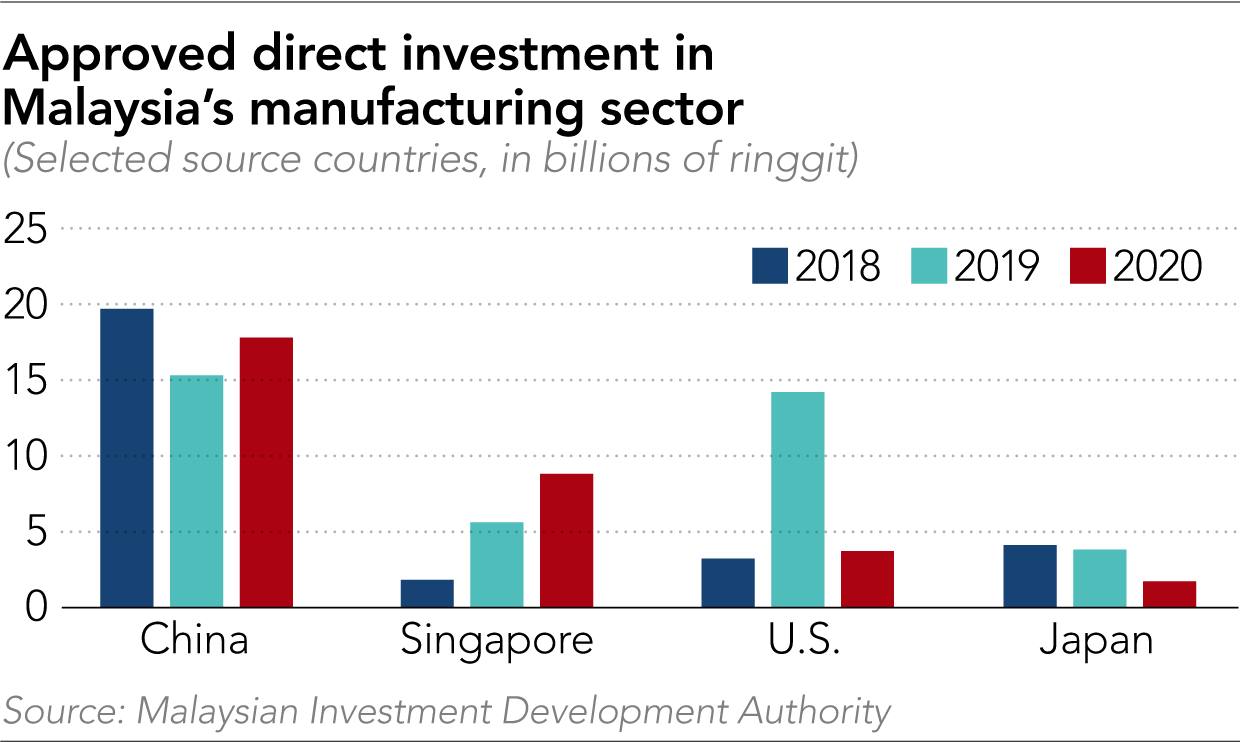

But times change. Exactly 40 years later, Malaysia is increasingly shifting its gaze northward to China for trade and foreign direct investment — particularly in manufacturing as it strives to climb the global value chain.

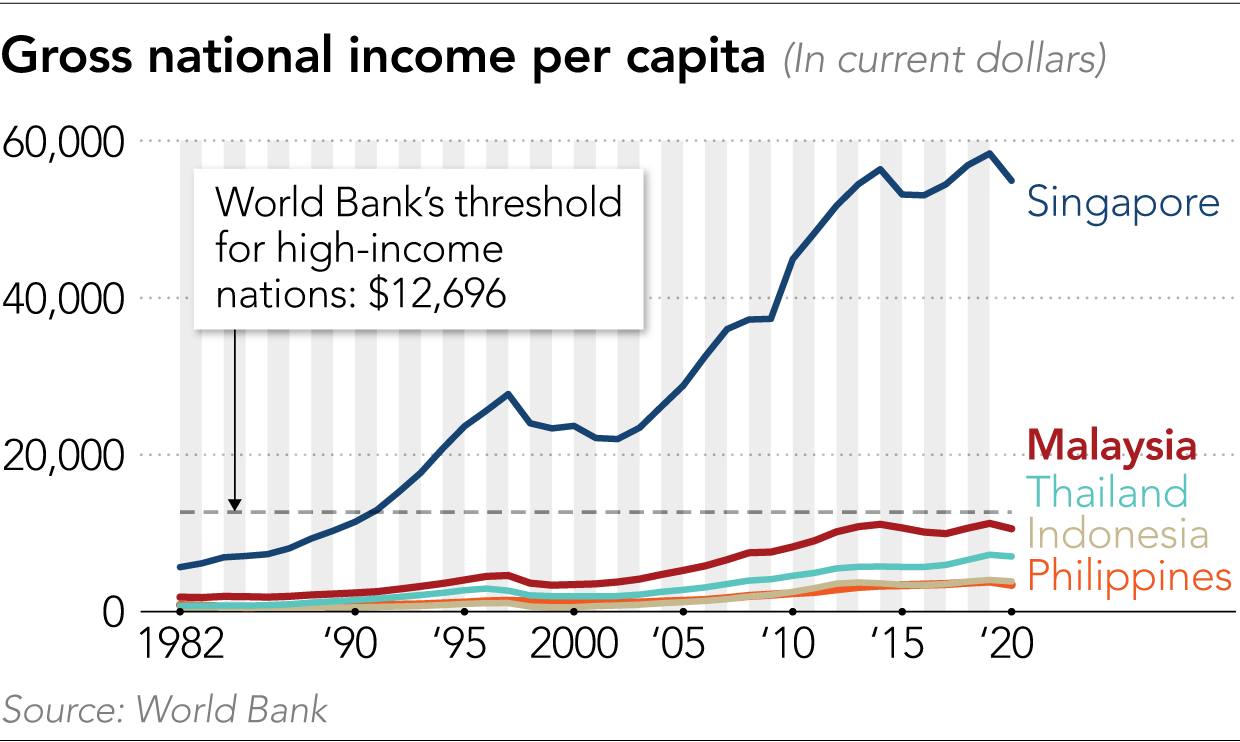

The shift comes as Malaysia attempts a final push toward high-income nation status. Only 19 countries with populations of over 1 million have joined that club in the last 30 years, according to the World Bank, which sets the bar at $12,696 in gross national income per capita. The bank sees the nation crossing the threshold between 2024 and 2028; the government of Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob is aiming for 2025.

Yet, even as it nears that milestone, the nation of over 32 million seems to have more questions than answers.

A World Bank report last year warned the country will cross the income threshold at a slower pace than others in recent decades, with “a lower share of employment at high skill levels and higher levels of inequality.”

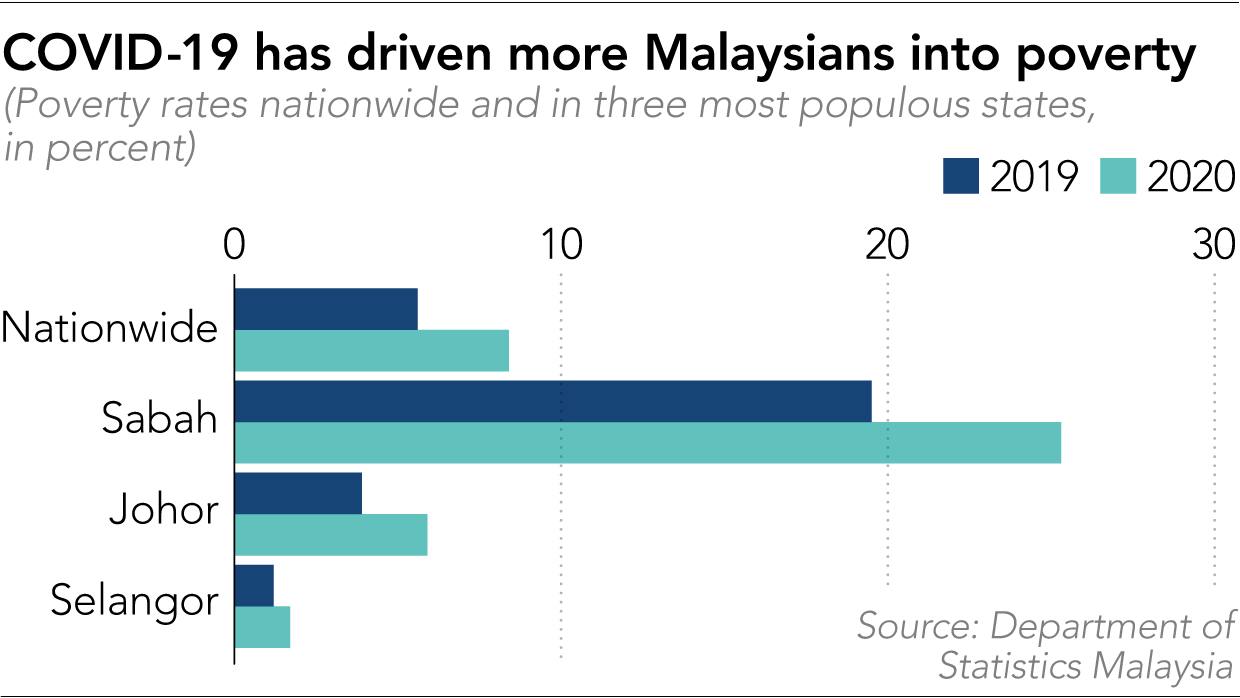

Meanwhile, COVID-19 has pushed more citizens into poverty. The stain of 1MDB, one of the biggest financial scandals ever, continues to mar Malaysia’s reputation. And fractious politics have brought down two governments in the past two years, with an election due by 2023.

When Mahathir introduced Look East, he sought to emulate the economy Japan had built on the ashes of World War II. “Malaysia identified what we believed to be the factors which contributed toward Japan’s success,” he recalled years later in a speech. “Patriotism, discipline, good work ethics, [a] competent management system and above all the close cooperation between the government and the private sector.”

Perodua’s President and CEO Zainal Abidin Ahmad told Nikkei Asia he was “thankful” for Look East and Daihatsu, which “not only brought engineering expertise but also qualities like punctuality, discipline and efficiency.”

Whether Malaysia correctly pinpointed the propellants of Japan’s ascent is a matter for debate. So are the questions of how much, and in what way, Look East contributed to Malaysia’s progress. Calvin Cheng, a senior analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia (ISIS), sees the policy as a “geopolitical initiative rather than a true economic development strategy” — a “symbolic move away from the West” by a prime minister known for his “Buy British Last” campaign and stinging critiques of America.

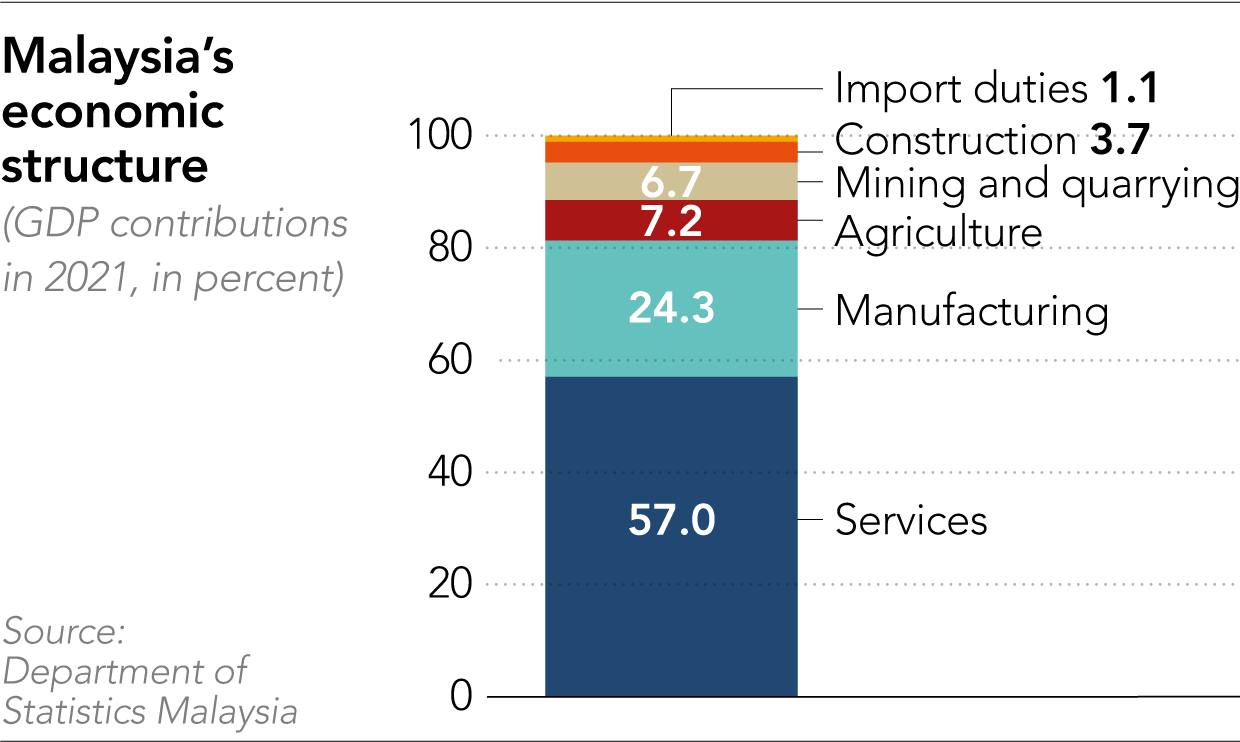

“The Look East policy resulted in stronger Malaysia-Japan bilateral relations, regional cooperation and cross-cultural relations,” Cheng said. But even before Mahathir rose to power, he noted that Malaysia had “aspirations to transition and diversify the then-mostly agrarian economy toward a technology-intensive manufacturing powerhouse.”

Intel arrived in 1972, helping to turn Penang — a center of the spice trade and British colonial entrepot on the Strait of Malacca — into a hub for microelectronics assembly, packaging and testing.

Still, Look East paved a path for Japanese and South Korean manufacturers to set up Southeast Asian bases in Malaysia. Under a state-sponsored education program, Malaysian students and industrial trainees were sent to Japan. To date, about 26,000 have studied at Japanese universities, according to Japan’s ambassador to Malaysia, Katsuhiko Takahashi.

Takahashi told Nikkei that having a Japanese-trained workforce enhanced the country’s appeal. “As a result, we now have around 1,500 Japanese companies here, partly because they can find Malaysians who can speak Japanese and help them do business,” he said.

Toray, Toshiba, Hitachi, Sony and Panasonic are among the brands with plants or distribution facilities. Japanese investment in Malaysia is estimated at over 80 billion ringgit ($19 billion) since the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1957, data from the embassy shows.

Malaysia’s rapid industrialization in the 1980s and 1990s earned the country a place among Asia’s “little dragons,” with annual gross domestic product growth reaching about a 10% clip before the currency crisis of 1997-1998. But fault lines had opened along the way.

Lee Hwok Aun, senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said the main impacts of Look East were on heavy industries such as steel, cement and the advent of the Mahathir- and Mitsubishi-backed Proton, the national carmaker, along with the rise of in-house unions as opposed to industrywide ones.

“Malaysia’s heavy industries push badly faltered, mostly closing shop, or in the case of Proton, survived through protection and failed to become competitive and innovative,” Lee said. “The in-house union approach crippled worker bargaining power in the context of very hierarchical workplaces, concurrently stifling wage growth, advancement in labor standards, and technological upgrading.”

Proton is as emblematic of Look East as it is the changing regional order.

Founded in 1983, the automaker was a product of technology transfers and capital investment from Japan’s Mitsubishi Group. But Mitsubishi pulled out in the mid-2000s and — squeezed between Perodua and foreign brands — Proton’s domestic market share plunged from over 70% in 1993 to just 12.5% in 2016. The following year, it was bailed out by China’s Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, which acquired a 49.9% stake.

“They say Proton is my brainchild,” Mahathir blogged. “Now the child of my brain has been sold.” He predicted Geely’s money and technology would someday allow Proton to compete with “Rolls-Royce and Bentley” but insisted he would take no pride in success “that does not belong to me or my country.”

The Proton sale was not the only deal that highlighted unease over Malaysia’s position relative to China, the country’s top trade partner since 2008.

The same year, China landed its largest infrastructure contract in Malaysia so far, to build a 688 km cross-country railway as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. The arrangement was controversial, not least because it was orchestrated under then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who faced suspicions over $4.5 billion allegedly misappropriated from 1MDB, the state wealth fund he had created.

“Even within the Malaysian political establishment, there were quiet, but growing, worries that Najib could compromise Malaysia’s institutional integrity or even its sovereignty with his fervent courtship of Chinese investment,” according to an analysis published last year by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

After Najib lost the 2018 election to Mahathir — who returned to the prime minister’s office for a second stint at the age of 92 — the railway project was scaled down, shaving off a third of the cost to 44 billion ringgit. Mahathir also suspended China-backed gas pipelines and warned against “a new version of colonialism,” though he acknowledged in a 2019 Nikkei interview that friendly relations were preferred since China was “too big now for us to ignore.”

Najib, for his part, went on to be convicted on multiple corruption charges in connection with a 1MDB subsidiary, pending an appeal to the apex court. Malaysia’s score on Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index has been sliding and now politics have come full circle.

Mahathir’s downfall in early 2020 and successor Muhyiddin Yassin’s resignation last August put Najib’s United Malays National Organisation back on top, led by Ismail Sabri. Mahathir himself, now 96, has been in and out of hospital recently. The rail project is expected to be completed by 2026, at a re-inflated cost of 50 billion ringgit.

“Relations between China and Malaysia deepened considerably under the pre-2018 UMNO-led government, so Beijing will likely welcome its old friends being back in power in Malaysia,” said Peter Mumford, practice head for Southeast Asia at risk adviser Eurasia Group.

Beijing’s overlapping claims in the South China Sea remain a friction point — as they do for several Southeast Asian neighbors — but the tensions “have not resulted in either side wishing to reduce economic cooperation,” Mumford said.

Various factors, he predicted, will “make Malaysia more reliant” on Chinese trade and investment: its delayed ratification of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade pact with Japan and others; a lack of progress on bilateral trade deals with the European Union and U.K.; and U.S. import bans on Malaysian rubber glove and palm oil producers over alleged labor abuses.

Malaysia appears to be looking to China — its top source of manufacturing FDI for the past several years — for a lift up the value ladder. In late 2020, the head of the Malaysian Investment Development Authority at the time called for Chinese investment, particularly in high-tech sectors. He rattled off a list of targets, including robotics, aerospace, biopharma, IT and new energy vehicles. This, he said, would “undoubtedly be instrumental in pushing our economic reformation despite the pandemic.”

After a recent ministerial meeting in China, the foreign ministry said Malaysia was looking for “new areas” of cooperation encompassing cybersecurity, digital technology and vaccine research.

Japan may yet help too. It “continues to be an important FDI source,” Cheng at ISIS noted. “There is a sense that Malaysia is now seeking not just foreign capital, but focusing more on how that capital can lead to greater local economic and human capital development.”

The World Bank suggests Malaysia occupies an intermediate value chain spot among global peers, still with many “backward linkages” that indicate an emphasis on assembly tasks. The bank also warns that Malaysia trails “in digital connectivity, innovation, and technology adoption by business,” with persistent gaps in human capital development “particularly among lower-income households.”

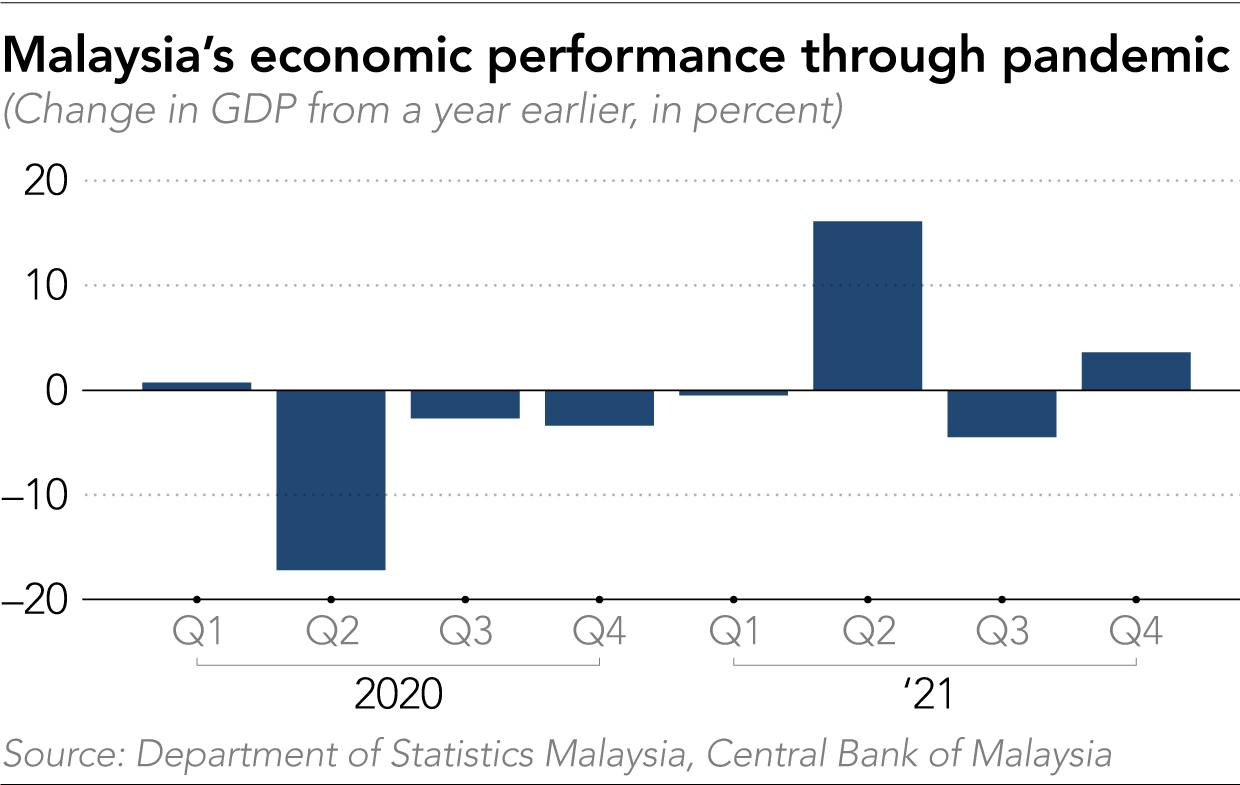

Improving the lot of such families is a pressing task, especially after COVID-19, which has infected about 3 million Malaysians and killed roughly 32,000.

Cheng said the labor impact of the pandemic has been “overwhelmingly severe and unequal,” noting that the poverty rate rose to 8.4% in 2020.

At least the economy is growing again, with the central bank last Friday reporting a 3.1% rise in GDP for 2021 after the 5.6% contraction in 2020. And similar to Thailand and the Philippines, Malaysia aims to completely reopen its borders next month.

Ismail Sabri has vowed that “by 2025, Malaysia would be a high-income and high-tech nation with a better quality of life.” Lee argued there are more meaningful factors to consider beyond the “numbers game” of high-income status.

“Persistently low wages, poor quality of education, low-skilled employment and inadequate social safety nets constitute the most important challenges,” Lee said. In schooling, Malaysia scored below the OECD average in reading, science and math in the latest available Program for International Student Assessment.

On the bright side, he said Malaysia has shown “institutional maturation,” with peaceful changes of government and more competitive elections, as well as steady macroeconomic and health management.

But the volatile alliances that stitch governments together and a “chronic inability to root out corruption surely undermine the ability to coordinate dynamic investment and sustain economic progress.”

Whichever direction it looks, how Malaysia confronts these problems will determine its path over the next 40 years.

Additional reporting by James Hand-Cukierman in Tokyo.

This article first appeared in Nikkei Asia on 15 February 2022.