Thomas Daniel was quoted on Southeast Asia Globe, 16 March 2022.

Regional analysts consider Russia’s military action and the possible consequences for ASEAN nations

Written by Brian P. D. Hannon, Fiona Kelliher, Govi Snell and Ashley Yeong

Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the opening of a “special military operation” into Ukraine on 24 February. That technocratic euphemism has blossomed into a full-scale war replete with missile strikes, hammering artillery, tanks rolling through strategic city gates and hostile troops enveloping the country

The invasion has created more than 3 million refugees and driven another 1.5 million ‘internally displaced’ people from their homes, according to the United Nations. The tools of war have tragically ended an unknown number of lives, including civilians and soldiers shrouded in plastic and carpets and lowered into mass graves in the port city of Mariupol.

Although the brutality of Russia’s invasion so far remains confined to Ukrainian territory, the instigator’s deep political and business ties have caused ripples far beyond the front lines.

Conversations with Southeast Asia experts revealed the myriad ways the conflict in Eastern Europe has already touched ASEAN countries, with additional reverberations set to follow.

Official responses from Southeast Asian governments have been mixed. In the first 36 hours following the invasion, Singapore and Indonesia condemned Russia’s attack, Malaysia expressed ‘sadness’ and Thailand was trying to repatriate its citizens, the South China Morning Post reported. The Philippines denounced the invasion in a 28 February statement, news outlet Rappler reported.

The UN General Assembly issued a resolution on 2 March calling on Russia to end the Ukraine offensive and withdraw its forces. A vote on the measure included 141 nations in favour, five opposed and 35 member states abstaining, including China, Laos and Vietnam.

Impact on ASEAN

The short-term consequences for Southeast Asia are debatable.

Thomas Daniel, a senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) in Malaysia, called the ASEAN response “mixed and generally restrained.” Diplomatic relations with Russia are expected to continue, though perhaps at a slower pace and with the possibility of attempts to politically isolate the invading nation if civilian casualties or other violations become impossible to ignore.

Yet ASEAN action is a consensus of all 10 members, meaning “decisions are often the lowest common denominator,” he said.

Lucas Myers, a programme coordinator and Southeast Asia associate at the Wilson Center, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C., also observed a “somewhat muted” ASEAN response, likely resulting from concerns over alienating Russia.

“Only the Myanmar junta gave a full-throated endorsement of Russia’s position, and Vietnam and Laos’ abstentions in the UN General Assembly vote were not as strong a statement of support as a ‘no’ vote would have been,” Myers said, adding that sanctions against Russia carry the risk of impacting energy investments and arms sales to Southeast Asia.

“This will make it harder to acquire Russian arms for countries like Vietnam and incentivise looking elsewhere for new weapon procurements,” Myers said. “However, any transition away from Russian arms would take many years and be very difficult for regional militaries.”

Gilang Kembara, a researcher with the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta, said Indonesia appears to be among the nations reluctant to strain their Russian relationship.

“Domestic opinion indicates that any support given towards Ukraine would indicate Indonesia’s willingness to ‘follow the Western narrative,’ or to be ‘pro-West.’ Such [a] position has so far been quite unpopular with the public, which has led to an increasing support of Russia, predominantly in social media,” Kembara said.

He added that there continue to be attempts by Ukraine and Russia to present their sides to civil society organisations and news outlets in Indonesia: “It would appear that the battle to gain public support in Southeast Asia is still ongoing.”

Dr. Zachary Abuza, a professor of national security strategy and a Southeast Asia expert at the National War College in Washington, D.C., said most ASEAN nations do not appear “willing to punish Russia for their illegal war of aggression,” but the length of the war and the “degree of devastation” against civilian populations will likely factor into future diplomatic relations.

Russia has “zero soft power” among ASEAN countries. “Southeast Asia has never been a priority region for Russia, beyond arms sales. It has been opportunistic, taking advantage of coups in Thailand, Myanmar and the rise of Duterte [in the Philippines], but there’s been little follow through,” Abuza said.

Still, the smaller nations of Southeast Asia are not expected to take a firm stand as a diplomatic bloc, he said.

“The two ASEAN statements [on 26 February and 3 March] have been so meaningless, refusing to name Russia, call it an aggressor or to use the word invasion,” Abuza said. “Most governments in Southeast Asia want to be neutral. This is dangerously naive. You are either on the side of international law or you are on the side of a revanchist power that has rejected a nation’s sovereignty and right to exist.”

Dr. Chin Kok Fay, a political economist at the National University of Malaysia, said Malaysia has taken a diplomatic “cautious approach” in line with a hedging strategy to avoid undermining its national interests.

“Most governments in Southeast Asia want to be neutral. This is dangerously naive.”

– Dr. Zachary Abuza, professor of national security strategy and Southeast Asia expert at the National War College, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Marek Rutkowski, a global studies lecturer at Monash University Malaysia, said Malaysia’s response has been “underwhelming,” in part because it is another Russian arms customer but also due to a realpolitik strategy leading the country to vote for the UN resolution while opposing unilateral sanctions.

“There is probably not much more that can be expected given that the conflict is far removed from the Malaysian borders and a restrained response seems like a pragmatic choice,” he said, noting that the invasion goes against ASEAN’s core philosophy.

“ASEAN has always upheld the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, non-interference in internal affairs of states and adherence to international law,” Rutkowski said.

“These principles, essential to the wellbeing and survival of Southeast Asian nations, have been grossly violated by Russia in Ukraine,” he said. “Given that the presence of a large and powerful neighbour, China, looms over ASEAN, it is possible to see potential dangers if Russia’s aggression goes unchecked.”

China’s shadow

Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Hua Chunying cast blame for the invasion on the U.S. and NATO: “Those who follow the U.S. lead in fanning up flames and then shifting the blame onto others are truly irresponsible,” she said on 24 February, a day after pointing the finger at NATO expansion “all the way to Russia’s doorstep.”

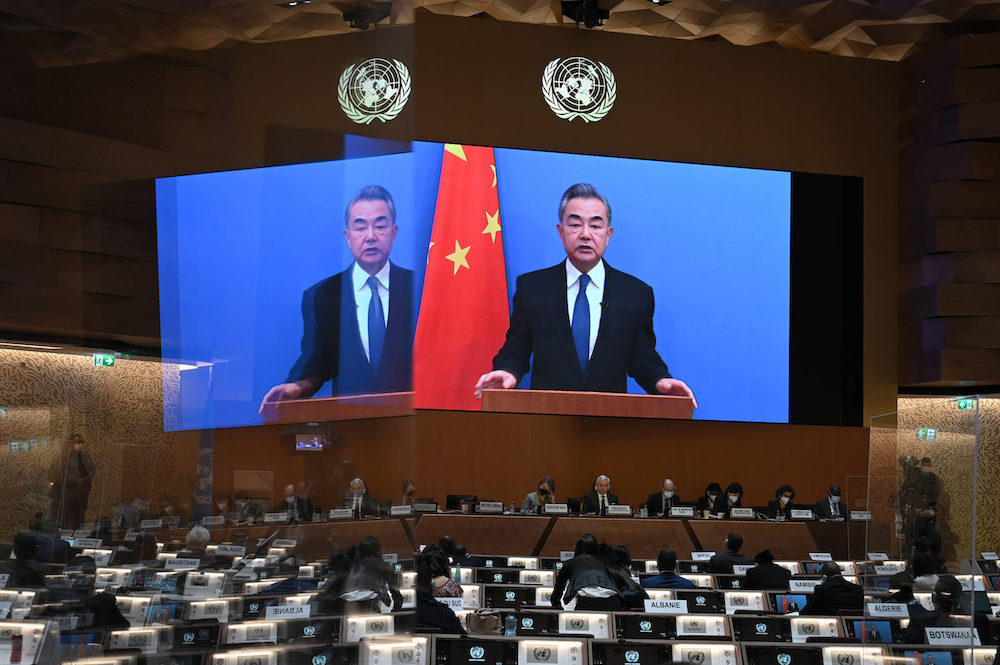

Foreign Minister Wang Yi said during a 7 March news conference that his nation “will maintain our strategic focus and promote the development of a comprehensive China-Russia partnership in the new era.”

Daniel of ISIS Malaysia said China’s supportive stance on Russia’s invasion likely has influenced governments in Southeast Asia, “especially for countries that are part of, or have interest in, the South China Sea dispute.”

“Some of Russia’s narratives of Ukraine and its history are worryingly similar to Beijing’s justifications for its claims on the South China Sea,” Daniel said. “China’s implicit and explicit support, or countenance, of Russia’s action should be of concern to Southeast Asia.”

Abuza said China’s position “should set off alarm bells across Southeast Asia.”

“China continues to blame the United States and NATO for the war, not the unilateral decision of Russia to invade a sovereign country with 190,000 troops,” he said. “China has signed off on Russia’s ‘legitimate security concerns’ and its doctrine of ‘limited sovereignty.’ I know China always says sovereignty is at the core of its foreign policy, but their actions should speak loudly.”

Myers said the alignment between the larger nations against the U.S. could indicate to ASEAN nations that Russia cannot be relied upon to challenge China in a regional crisis, such as a South China Sea dispute. ASEAN subsequently may look for other political partners while trying to maintain long-term ties to Russia.

Most ASEAN countries joined the UN resolution, likely due to concern over the ramifications for smaller nations of China’s growing power, Myers noted.

“Over the long term, many in Southeast Asia do not want to abandon their burgeoning ties with Russia because Moscow is viewed as an important partner for avoiding dependence on China,” he said, adding that Cambodia’s vote for the resolution demonstrated autonomy from China despite the larger nation’s substantial influence.

“It appears that many in Southeast Asia still wish to maintain relations with Russia over the long-term despite its unreliability, and only Singapore is willing to join the sanctions regime at this time,” Myers said.

” Only Singapore has been willing to join the sanctions regime and do something about it.”

– Sophal Ear, associate dean, Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management

Chin said Southeast Asian nations are “deeply concerned” over Ukraine, but there are few short-term implications in the region except possibly for Singapore, which he said has been added to Russia’s list of ‘unfriendly foreign states.’”

Sophal Ear, associate dean of Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management, said statements from Southeast Asian nations have been “lukewarm” at best due to concern for overseas workers, students studying in Russia and weapons deals.

“What it says to me is they don’t want to touch this with a 10-foot pole in terms of sticking their necks out,” Ear said. “Only Singapore has been willing to join the sanctions regime and do something about it. I’d say everybody else is looking down at their shoes and making vacuous statements.”

Abuza also singled out Singapore as the “only country in Southeast Asia that has taken a strong and principled position” against the invasion.

“They understand the very dangerous legal precedent the Russian invasion sets,” Abuza said. “The alteration of borders by force, the invasion and decapitation of a country’s leadership, the neutralisation of a state at gunpoint. Russia’s actions create a terrible precedent for small states, and sadly most Southeast Asian states have been largely in denial.”

The economics of war

The potential financial implications for Southeast Asia are mixed, although analysts seem to agree military transactions and fuel prices are the obvious contenders.

Nguyen Khac Giang, a doctoral candidate focusing on Vietnam and Asian affairs at the Victoria University of Wellington, said Vietnam has an important economic stake in Russia beyond arms sales. Many Vietnamese live and work there, while the loss of Russian travellers will be a blow to tourist businesses as Vietnam reopens following Covid-19 restrictions.

Daniel predicted possible short-term to midterm price impacts on food in Malaysia, which uses Russia and Ukraine as major sources of wheat and grain. Abuza also said regional wheat prices could soar and are likely to hit Indonesia hard, while Thailand could see a dip in tourism.

Approximately 17,600 Russians travelled to Thailand in February, which the Public Health Ministry said was 8.6% of total visitors. Those numbers dropped off after the 24 February invasion, in part because of credit card companies and airlines joining sanctions. About 6,500 Russian and 1,000 Ukrainians tourists have remained in Thailand, although some are struggling to pay their tabs without credit cards, The Associated Press reported on 13 March.

But Abuza stressed there is limited trade between Russia or Ukraine and Southeast Asia and very little Russian investment. Global markets rather than Russian action will raise energy prices. There will be a military impact on Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, which tops ASEAN trade with Russia, although still not as much as Vietnam’s transactions with neighbouring Cambodia.

“I can’t emphasise enough how unimportant Russia is to the region economically, with perhaps the exception of money laundering,” Abuza said.

President Joe Biden on 8 March announced a halt to U.S. imports of Russian oil, an attempt to hamper Russian cash flow and force a military withdrawal. The U.S. increased the pressure on 11 March, removing Russia’s ‘most favoured nation’ trading status and banning imports of Russian alcohol, diamonds and seafood. A Kremlin spokesman accused the American government of launching “an economic war” on Russia.

The European Union also has issued targeted economic sanctions on Russia and its ally, Belarus, and is considering Ukraine’s request to accelerate its EU membership application.

Myers said the oil ban by the U.S. and the United Kingdom, which plans to discontinue imports by year’s end, could also impact Southeast Asia economies as higher global energy costs slow growth and raise consumer prices.

“Growing pressure on Russian energy firms may also cause actors in Southeast Asia to question Russia’s role in energy extraction in the region,” Myers said.

Kembara of CSIS said there might be a financial benefit for ASEAN. “As more and more Western nations sanction and boycott Russian-made products and commodities, this will push them to find commodities from alternative markets such as Southeast Asian nations,” he said.

Ear of Arizona State University, a Cambodian native and political specialist, said some Cambodians believe invasions can be “liberatory,” stemming from Vietnam’s 1979 move into Cambodia that ultimately defeated the Khmer Rouge and was subsequently celebrated as Liberation Day or Victory Day.

That is not the case in Ukraine, he said.

“There is no regime that has enslaved its people like the Khmer Rouge did that needed to be removed and decapitated,” Ear said. “This is not the same situation, even if someone delusional might say it is.”

This article was first published in Southeast Asia Globe, 16 March 2022.