Haris Shaiful was quoted on South China Morning Post, 15 February 2023

- Chinese consumers are enjoying unprecedented access to the Southeast Asian delicacy known for its intense smell and unique taste, thanks to recent bilateral agreement

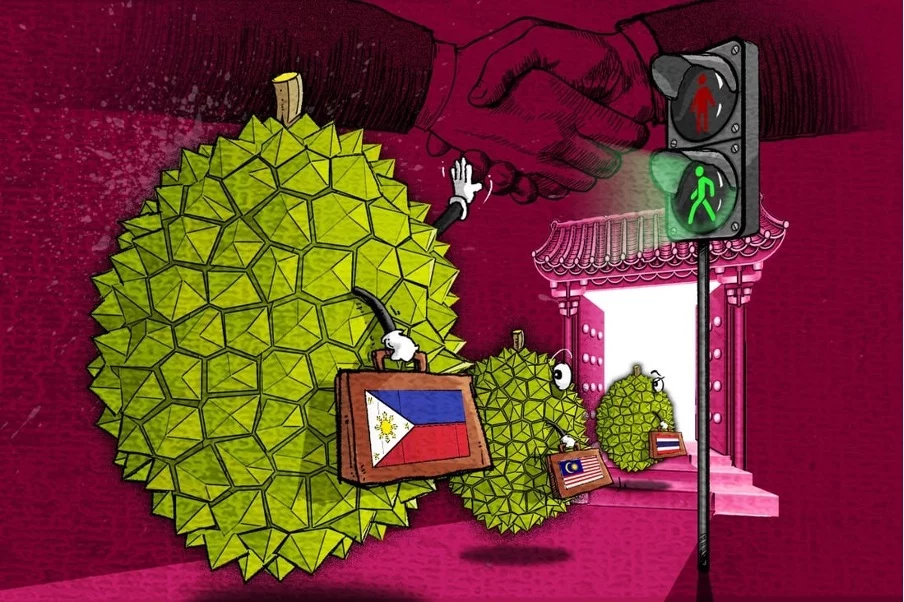

- But the emergence of ‘durian diplomacy’ has some Asean countries turning up their nose at what they see as political manoeuvring that could eventually backfire

Ji Siqi, Ralph Jennings, and He Huifeng in Guangdong

More than 900km southeast of Manila, Davao City is dubbed “Durian Capital of the Philippines”. With the volcanic soil of Mount Apo said to give the pungent “king of fruit” a unique flavour, the region accounts for almost 80 per cent of all durians grown in the country.

But now, even the local durian market in Davao is in short supply, as large amounts of the existing harvests have been reserved for China.

It all began with a new bilateral agreement signed between the two countries in early January, following the state visit of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr to Beijing, which opened China’s door to fresh Philippine durians for the first time.

“China, because of their population, is a really significant destination for exports,” said Faye Oguio, operator of a three-hectare (7.4-acre) durian farm in Davao.

But at the same time, the news also frayed nerves in neighbouring countries, including Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia, especially as many observers have been increasingly ascribing political significance to the durian trade – despite being a tiny entry in the trillion-US-dollar annual trade between China and Southeast Asia.

With a putrid smell and thorny rind, the tropical fruit is an indigenous fruit of Southeast Asia, but China is its biggest market, where cakes and pastries made with durian have deep roots in the nation’s cooking culture.

“Durian is a fruit that can represent the identity of Southeast Asia,” said Xie Kankan, assistant professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Peking University.

“So, the durian trade has more cultural and symbolic meanings, as it signifies the special relations between China and the region, which can be different from the simple economic engagement that it has with the West,” Xie explained.

In the past year, China’s opening up of its market to more countries for fresh durians has been popularly labelled “durian diplomacy”, spurred by both the growing appetite of Chinese durian lovers and Beijing’s wish to cement its ties with Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) amid rising tensions with the United States, according to pundits.

And the preferential tariffs and faster customs clearance under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which entered effect in January 2022, have further added to the potential of the business, while such closer engagement also has the potential to be a huge source of leverage if political relations sour, they said.

For Zhejiang-based fruit importer Huang Dapeng, his durian business allowed him to experience first-hand how the demand from Chinese consumers has exploded, as the sales of his company, TC Durian, have maintained an annual growth rate of more than 50 per cent over the past five years.

“When we first invested in this business seven years ago, only people in Guangdong province and Hong Kong ate durian. But now, Chinese consumers across the country, from south to north, from women to children, all like durian,” said Huang, whose company’s annual sales revenue has reached 50 million yuan (US$7.4 million).

In 2022, China imported more than 824,000 tonnes of fresh durians, valued at more than US$4 billion. That was nearly four times the volume seen in 2017, and seven times the value, according to data from China Customs.

But for a long time, Thailand had been the absolute beneficiary of this fast-growing market, as only fresh durians from the country were allowed to be imported into China, while a smaller high-end market share was dominated by frozen durians from Malaysia. The monopoly was only broken in September, when Beijing approved 51 durian growers and 25 durian-packaging companies from Vietnam to export fresh crops to China.

Vietnam’s land border with China makes trade less difficult, which further enhances the competitiveness of its durians – of which the freshness is key to their quality, according to Jack Nguyen, a partner at the business advisory firm Mazars in Ho Chi Minh City.

“Vietnam grows a lot, so they need to export some of the crop,” he said.

Nguyen Thanh Trung, a political scientist at Fulbright University Vietnam, said the green light from China reflects its established inclination to improve diplomatic relations with other countries by choosing something in which China and its partners have deep converging interests.

“Durian exports to China would be something big in Vietnam, not because durian is a high-value export fruit, but because it signifies that China’s huge market is lifting its gate open for more imports of Vietnam’s agricultural products through official channels, not via informal border trade,” he said.

He said it would also help Vietnamese farmers – who account for a big portion of the country’s population – eye China as a potential market for other agricultural products.

In less than four months, the Philippines became China’s third approved fresh-durian exporter. A local agriculture official said the industry is expected to generate about US$150 million in income during the first year of trade with China, along with 9,696 direct jobs and 1,126 indirect jobs, according to the Philippine New Agency.

It is expected that more Southeast Asian countries will be added to China’s list of sources of durian imports, and now Chinese investments are flocking to these countries to build up more efficient local supply chains, said Huang, the Zhejiang importer. His company invested in packaging factories in Vietnam last year and is planning to expand into the Philippines and Cambodia later this year.

“In a broader picture, China demonstrates that they are a reliable and useful behemoth amid the increasing US-China competition in the [Southeast Asia] region,” said Nguyen from Fulbright University.

Li Mingjiang, assistant professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, said no Southeast Asian countries want to choose between the US and China.

“For now, certainly, they don’t have to choose, because there’s still a lot of room for them to manoeuvre,” Li said.

Li added that, while durian is just a very small part of the strong economic relationship between Southeast Asia and China, it can have some political implications, as robust economic ties highlight the importance of stable diplomatic relations.

Last year, Asean and China were each other’s biggest trade partners, with their total trade value reaching US$975.3 billion, according to China Customs data.

Accompanying the excitement of Vietnamese and Filipino farmers and exporters, following Beijing’s green light, were worries from Thailand and Malaysia.

“With the Philippines getting approval to export durians to China, Malaysia is at greater risk of losing market share,” said Haris Shaiful Bahari, a trade and economics researcher at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Malaysia.

But one advantage that the two long-time market players have is much less spillover risk from politics, according to experts.

Philippine durians can be used as a political symbol of bilateral relations, which China can use as leverage, said Andrea Chloe Wong, a former senior analyst at the Philippines’ Foreign Service Institute.

“Previously, China used Filipino bananas to also make a political point,” said Wong, who holds a PhD in political science from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

At the height of the bilateral tensions between the two countries during the Scarborough Shoal stand-off in 2012, Beijing imposed tighter controls and restricted imports of bananas from the Philippines, alleging that they had mealybugs.

Given that both Vietnam and the Philippines are engaged in territorial disputes in the South China Sea with China, they could be vulnerable if Beijing decides to punish them via trade, said Xie from Peking University.

“In fact, any excessive dependence on a single market will make the entire industry very weak. So, they are worried – if China is unhappy and suddenly stops importing durian, what will [Filipinos] do with them? They would be left to rot,” Xie said. “Thailand and Malaysia don’t have these concerns, as they don’t have such political disputes with China.”

Despite their soaring popularity in recent years, durians are far from a necessity for Chinese people, according to Jay Zhong, a durian importer in Guangdong.

“Durian is the same as the Australian rock lobster,” Zhong said, pointing to the crustacean that was once a staple delicacy at Chinese wedding banquets and parties. Beijing unofficially banned it along with other commodities, including copper, coal and wine, amid simmering political tensions with Canberra in late 2020. The bans have yet to been formally reversed, though Trade Minister Don Farrell reportedly told the Australian Broadcasting Corp last week that Beijing had not rejected a recent application by Australia for fresh lobster exports to China, hinting at a thaw in relations.

“No one can easily forgo the biggest piece of cake,” Zhong said of the Chinese market.

This article was first published in South China Morning Post, 15 February 2023