As Asean-India economic relations enter fourth decade, Malaysia could be key to deeper partnership

By Prabir De & Durairaj Kumarasamy

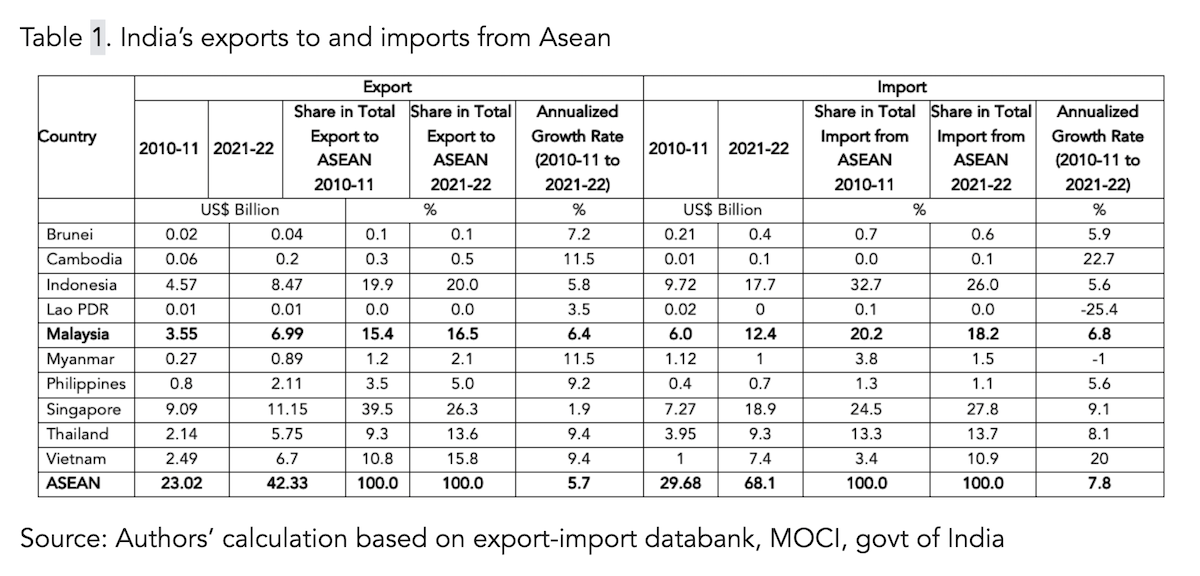

MALAYSIA is India’s third largest trading partner in Asean and at US$19.2 billion (RM87 billion) in 2021-2022, the figure represents almost 20% of India-Asean trade. India has had long-standing economic links with Malaysia whereby Indian industry played a pivotal role transforming the latter from an exporter of primary products into an industrialised and tech-based economy. Bilateral investment between the two countries has been growing steadily.

Malaysia’s foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into India are about US$1 billion (between 2000-2020), whereas India’s FDI is about US$1.70 billion (2008-2020) in Malaysia. Over time, India-Malaysia economic relations have moved faster than expected amid uncertainties. However, there remain several challenges in the trade and investment areas and unaccomplished tasks. Given Malaysia’s technological prowess in manufacturing and India’s in services, there could be many new opportunities. A healthy relationship between them can not only drive the Asean-India relations but also strengthen the Indo-Pacific.

Bilateral trade relations

Malaysia is India’s third largest trading partner in Asean after Indonesia and Singapore, whereas India is Malaysia’s largest trading partner in South Asia. Bilateral trade increased by 17 times from the US$600 million in 1992 to US$10 billion in 2008, before it declined to the US$8.4 billion in 2009 during the global financial crisis and rebounded to US$9.55 billion in 2010.

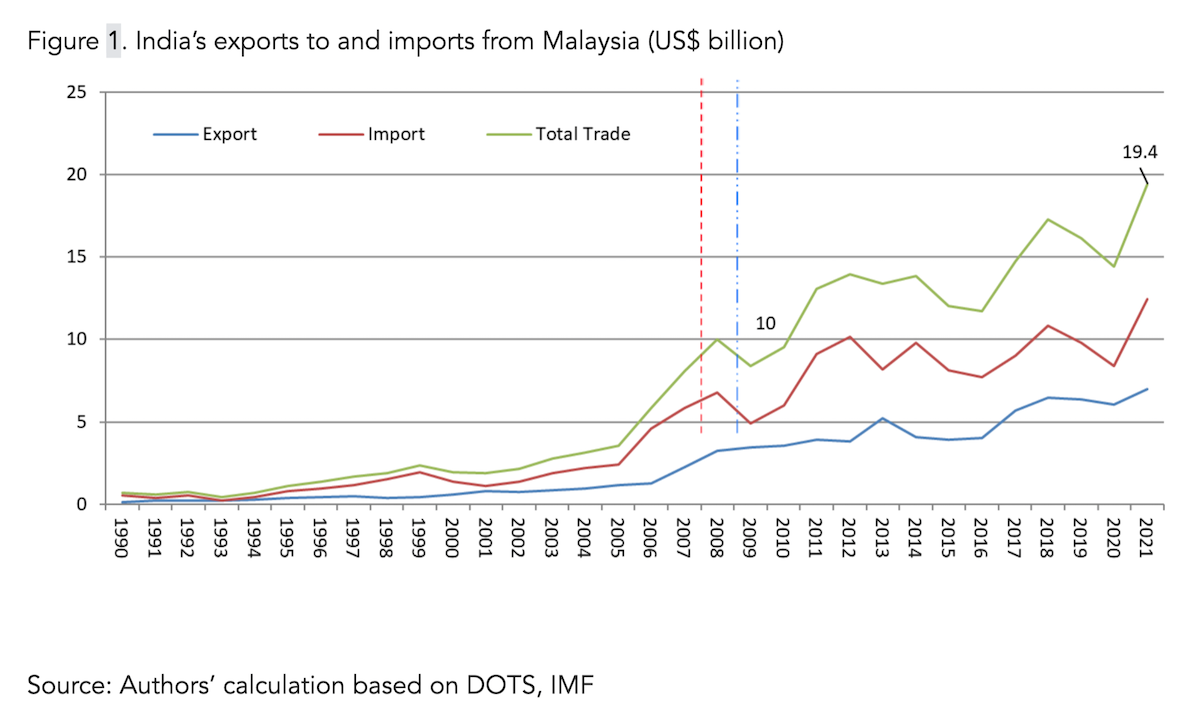

With the Asean-India Free Trade Area (AIFTA) that came into force in January 2010 and the Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic (MICECA) in 2011, India’s bilateral trade with Malaysia increased from US$10 billion in 2010 to US$19.4 billion in 2021, with an annualised growth rate of 7.2% (table 1).

Another important development is that bilateral trade remains significantly imbalanced. The balance of trade is in favour of Malaysia. For instance, in 2021-2022, India’s exports to Malaysia came to US$6.9 billion, whereas imports from Malaysia were US$12.4 billion. The imbalance with Malaysia widened during post-AIFTA and Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA), witnessing almost US$6 billion trade deficit with Malaysia in 2021-2022 (figure 1). India has drawn the attention of the Malaysian government to the importance of more balanced trade.

Investment relations

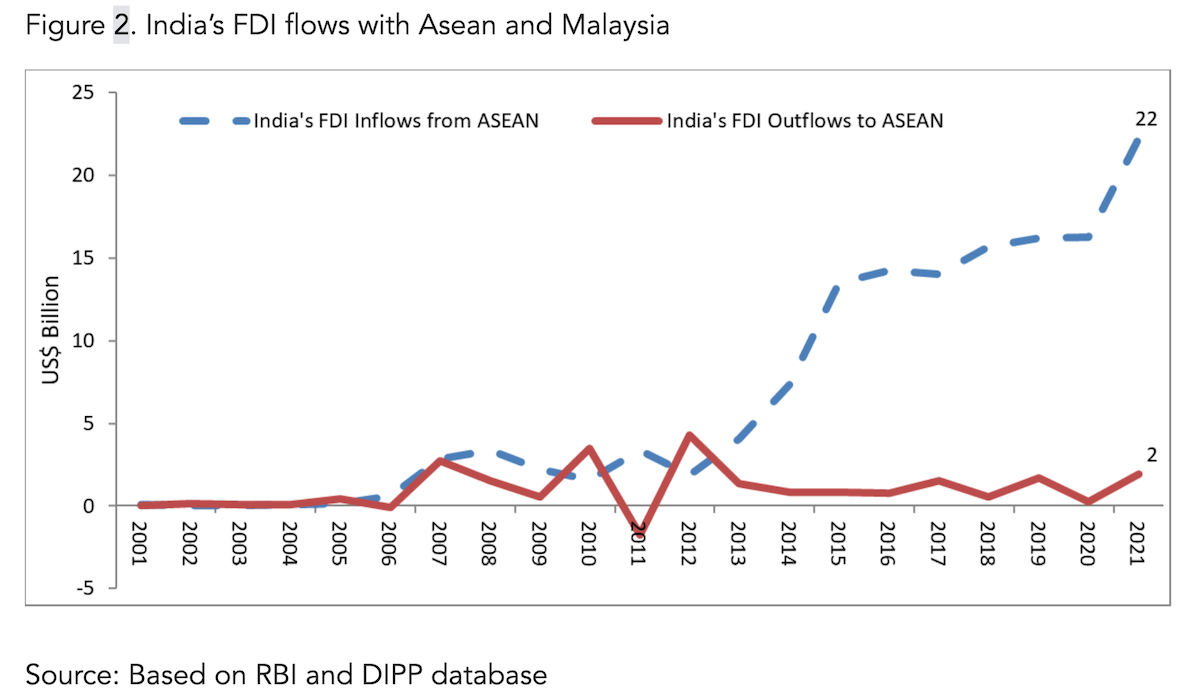

FDI inflows to India from Asean has been increasing rapidly since 2008 and reached about US$22 billion in 2021 (figure 2). India’s FDI outflows to Asean are almost stable at the range of US$2 billion. Asean accounts for 18% of all investment flows into India since 2000 (US$140 billion). India’s FDI to Asean is about US$26 billion since 2000 (figure 8).

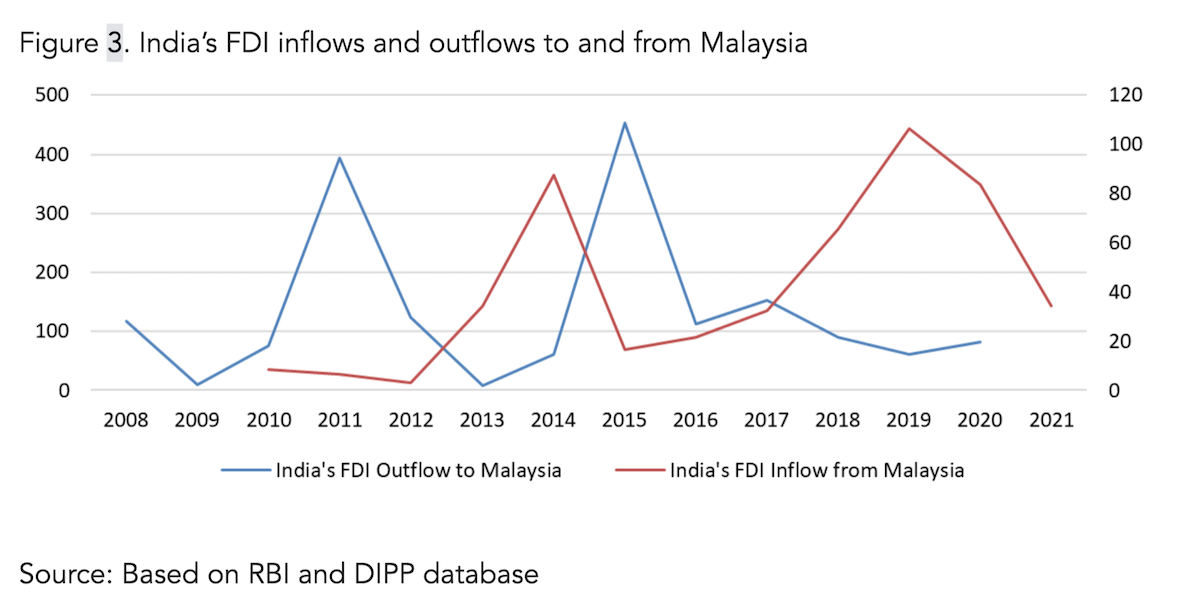

Among Asean, beside Singapore, India’s investment relation with Malaysia is one of the longest-standing commercial links. Indian industry has been associated for three decades with the transformation of Malaysia from an exporter of primary products into an industrialised and tech-based economy. Though there is no steady flow of bilateral investment between India and Malaysia, cumulative investment has grown steadily. For instance, Malaysia’s FDI is close to US$1 billion (US$906 million since 2000 till 2020) in India whereas India’s FDI is about US$1.7 billion (2008-2020) in Malaysia (figure 3).

Despite the favourable account of Indian investments in Malaysia, Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA) said Indian investors could still increase their footprints in the Malaysian economy. With the recent engagement with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) through the signing of MoUs, the exchange of business communities offers more opportunities and attracts quality investment proposals. Given the AIFTA and MICECA, the current scale of FDIs between them may be scaled up with investments in new business areas, such as digital economy, climate and environment, energy, health, among others.

Regional value chains

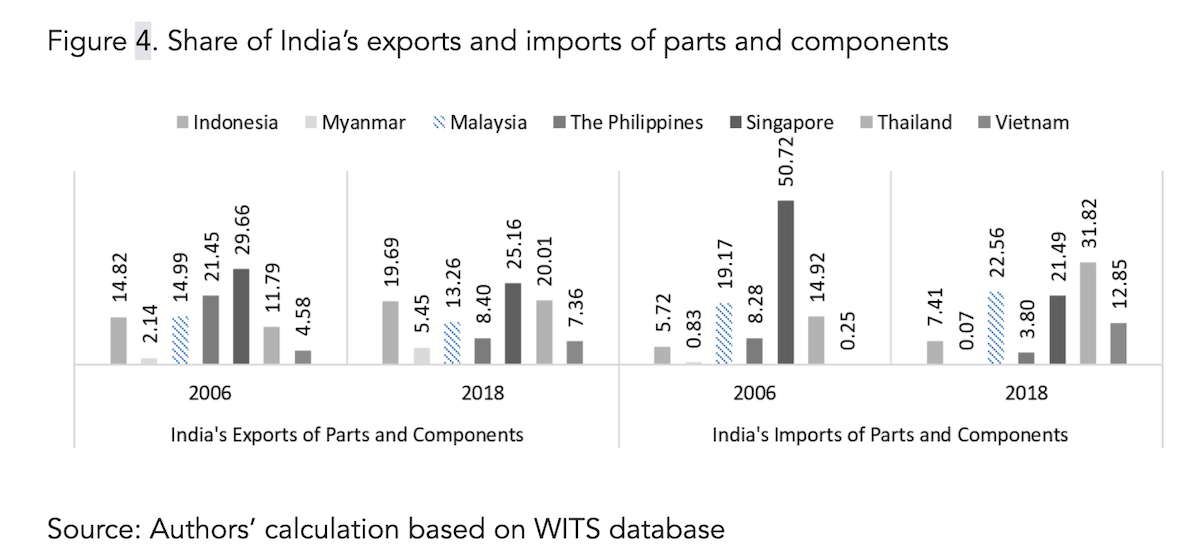

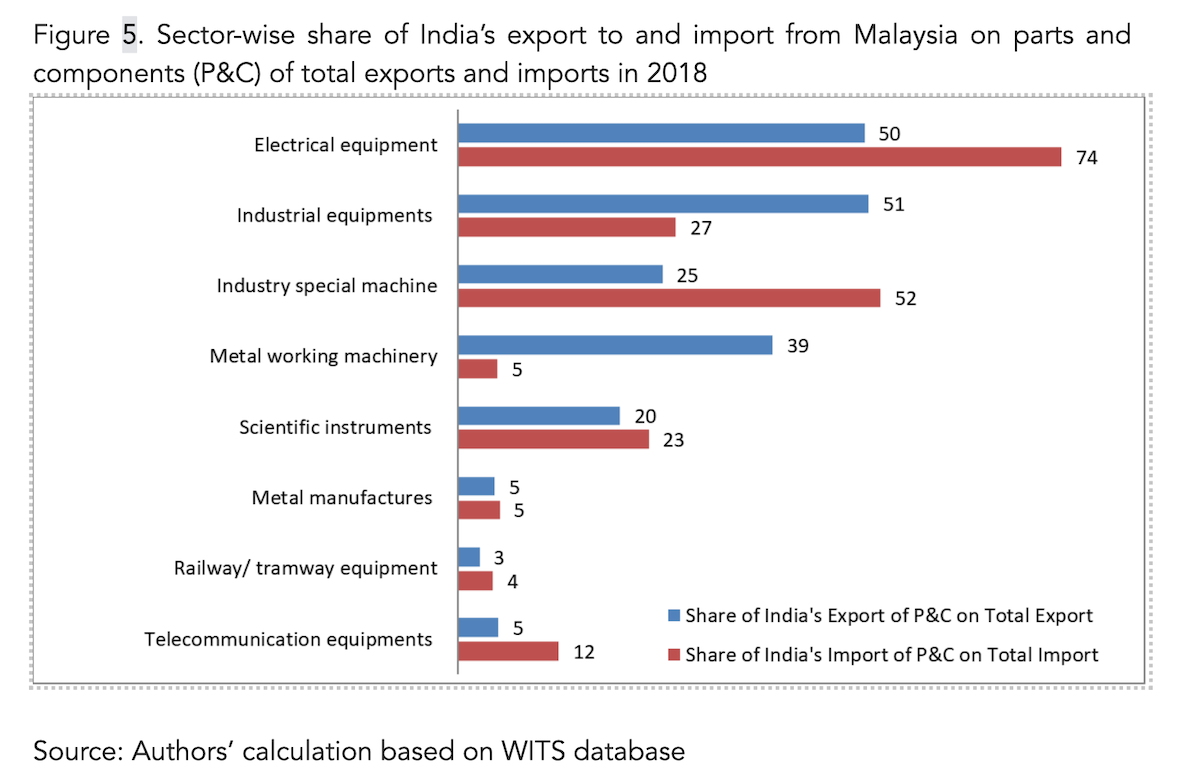

Among Asean countries, the share of India’s exports of parts and components (PC) to Malaysia is about 14% in 2018 to total India’s total exports of PC to Asean. On the other hand, the share of India’s imports of PC from Malaysia is about 23% in 2018 of total imports from Asean (figure 4). In terms of sectoral composition, most of the parts and components traded between India and Malaysia are electrical equipment, industrial equipment, metal working machinery, scientific instruments and telecommunications (figure 5).

A deeper and liberalised trade in goods and global value chain (GVC) linkages generates services trade and pushes up the integration to a higher level. India and Malaysia are yet to unlock the services trade potentials, except tourism.

Easing trade procedures

India is the fastest growing economy and has developed a comparative advantage in services, particularly IT services. India is presently attempting to foster manufacturing development and linkages to global value chains through the “Make in India” programme. About 25% of India’s global trade has been conducted with Southeast and East Asia. With Indo-Pacific in prominence along with a simultaneous rise in trade restrictiveness across countries, both India and Malaysia should strengthen the economic and investment relations by easing the burdens of non-tariff measures (NTMs), mutual recognition and harmonisation of standards, process simplification, e-trade and transparency.

Malaysia and India should utilise the synergy that exists between manufacturing and services trade. Malaysia has a trade surplus in goods and has a stronghold in electrical, electronics and machinery in addition to being a major supplier of palm oil to India, whereas India has a stronghold in services sectors in the areas of logistics, finance, IT and business professionals. Both should promote the areas which offer maximum gains.

There is a need to promote sectoral and issue-based cooperation, such as information and communication technology (ICT), energy, research and development (R&D), health, digital technology, e-commerce, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and GVC participation to maximise the trade and economic potential. Reducing tariffs and removing items from exclusion and sensitive lists for those products that are supporting regional value chain processes would also help. There is a need for reforms in NTMs and maintain consistency in standards to help firms to engage in regional value chain. Harmonisation of standards and convergence of testing and certification requirements would help the traders to ease the complex trade procedures.

For example, signing of the mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) in higher education, tourism industries, electrical and machinery industries and pharmaceuticals will pave the way for higher trade, investment and value chains. This will also further deepen the Asean-India relations in the fourth decade.

There are several opportunities in connectivity projects, such as development of ports and shipping, coastal management, construction of harbours. India-Malaysia partnership in the maritime sector will add momentum to the Indo-Pacific cooperation. Synergies should be explored between manufacturing and services trade to strengthen value chain linkages in areas like computer and related services, and various professional services, which are not undermined by regulatory barriers in the form of immigration, recognition and standard-related restrictions on the mobility of its service providers or by data protection-related challenges to IT-enabled service exports.

Finally, India and Malaysia are partners in the AIFTA in goods, services and investment. Both have also signed and implemented a bilateral CECA. Both are also partners in the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). India-Malaysia trade relations, therefore, have multidimensional potentials. When the world is passing through economic and political uncertainties, deepening Asean-India regional partnership offers high dividends, economic and otherwise. The India-Malaysia partnership stands high on its own. It is now time to unlock these ever-changing multidimensional potentials for speeding up economic prosperity.

Prof Prabir De is based at the Centre for Maritime Economy and Connectivity and Coordinator of the Asean-India Centre and Assoc Prof Durairaj Kumarasamy is head at Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies