Malaysia’s progressive wage policy

A guide to policy design considerations for effective implementation

by Calvin Cheng and Kevin Zhang, March 2024.

About the contributors

Calvin Cheng is a fellow in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. His research interests span issues in applied economics, centring around jobs, social protection, economic development and the design of social transfer programmes. He holds a MSc in Public Policy from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and a B.Econ in Economics and Econometrics from Monash University in Clayton.

Kevin Zhang is an associate senior research officer at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore and conducts Southeast Asian research, focusing on labour market, politics, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. He has a Masters of Comparative Politics from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and a bachelor’s degree from the National University of Singapore.

Executive summary

- Malaysia’s proposed Progressive Wage Policy (PWP) is a structured wage incentive programme inspired by Singapore’s Progressive Wage Policy. It is a voluntary programme targeted at micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), with the objective of boosting wage growth, productivity and skills development.

- As the PWP transitions to nationwide implementation after the end of the pilot in September 2024, crucial decisions regarding key design aspects of the PWP will need to be made, particularly as the white paper leaves out important details on how some aspects will be operationalised in practice.

- These important design considerations include whether the PWP should remain voluntary after the pilot phase ends. While a voluntary PWP could make it easier for small businesses to adapt in the short term, in the long term it may work to constraint the programme’s impacts on wages and productivity.

- Similarly, policymakers will need to decide on how inclusive coverage will be. In its current form, we estimate that the PWP will leave out most workers in Malaysia. When implemented nationwide, this will create significant trade-offs between its inclusiveness, effectiveness and overall costs.

- Looking at the post-pilot phase, policymakers should implement a gradual transition to mandatory compliance and expanded coverage, drawing from Singapore’s model. This could mean extending mandatory compliance on a sector-by-sector basis, while adopting a phased approach to expanding eligibility conditions across a more diverse range of workers and firms.

- Additionally, the PWP should be integrated closely with existing education and skills training institutions, including by establishing occupation-specific skill progression pathways using HRD Corp’s knowledge base. Likewise, greater integration between the PWP and TVET pathways and programmes like Academy in Industry (AiI) will improve its impacts and streamline implementation.

1. Overview of Malaysia’s Progressive Wage Policy

The Progressive Wage Policy (PWP) was proposed with the tabling of the Progressive Wage Policy White Paper in Parliament on 30 November 2023.¹ Inspired by Singapore’s Progressive Wage Model (see Box A for an overview), Malaysia’s PWP aims to support its transition into a high-income nation by boosting wages, productivity and skills development. Targeted at micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), this voluntary programme encourages firms to increase their employee’s salaries through a structured wage incentive system.²

Under the PWP, participating firms receive a monthly incentive of up to RM200 per entry-level employee and up to RM300 for those in higher positions – contingent upon those employees receiving wage increases in line with PWP salary guidelines and completing approved skills training programmes.³ The PWP currently only covers full-time workers in MSMEs earning under RM5,000 per month. For workers on a service contract, the contract duration must be at least 3 years to qualify.

These salary guidelines will be decided by a special working committee comprising the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR) and other relevant institutions.4 These guidelines will be updated annually and will vary across economic sectors and Malaysian Standard Classification of Occupations (MASCO) job category. Unlike the statutory minimum wage, PWP in its current form uses monetary incentives to encourage participation, with no penalties for non-participation.

The white paper and Ministry of Economy press releases indicate that the PWP will be piloted from June 2024 to September 2024, starting with 1,000 companies that have opted in.5 If rolled out nationally, this will be a significant addition to Malaysia’s labour market landscape, potentially having a transformative impact on wage growth, human capital and labour mobility.

Nonetheless, as the PWP transitions from the pilot stage to broader nationwide implementation, it becomes essential for policymakers to make important decisions regarding the PWP’s design, including whether it should be eventually made mandatory, and how broad the PWP’s coverage should be. At the same time, the PWP as proposed in the white paper leaves out crucial details on how it will be implemented and operationalised in practice. This policy brief addresses these information gaps, analysing the policy design options available to policymakers, and outlining policy recommendations to maximise its long-term impacts.

Box A. Overview and comparison of Singapore’s Progressive Wage Model

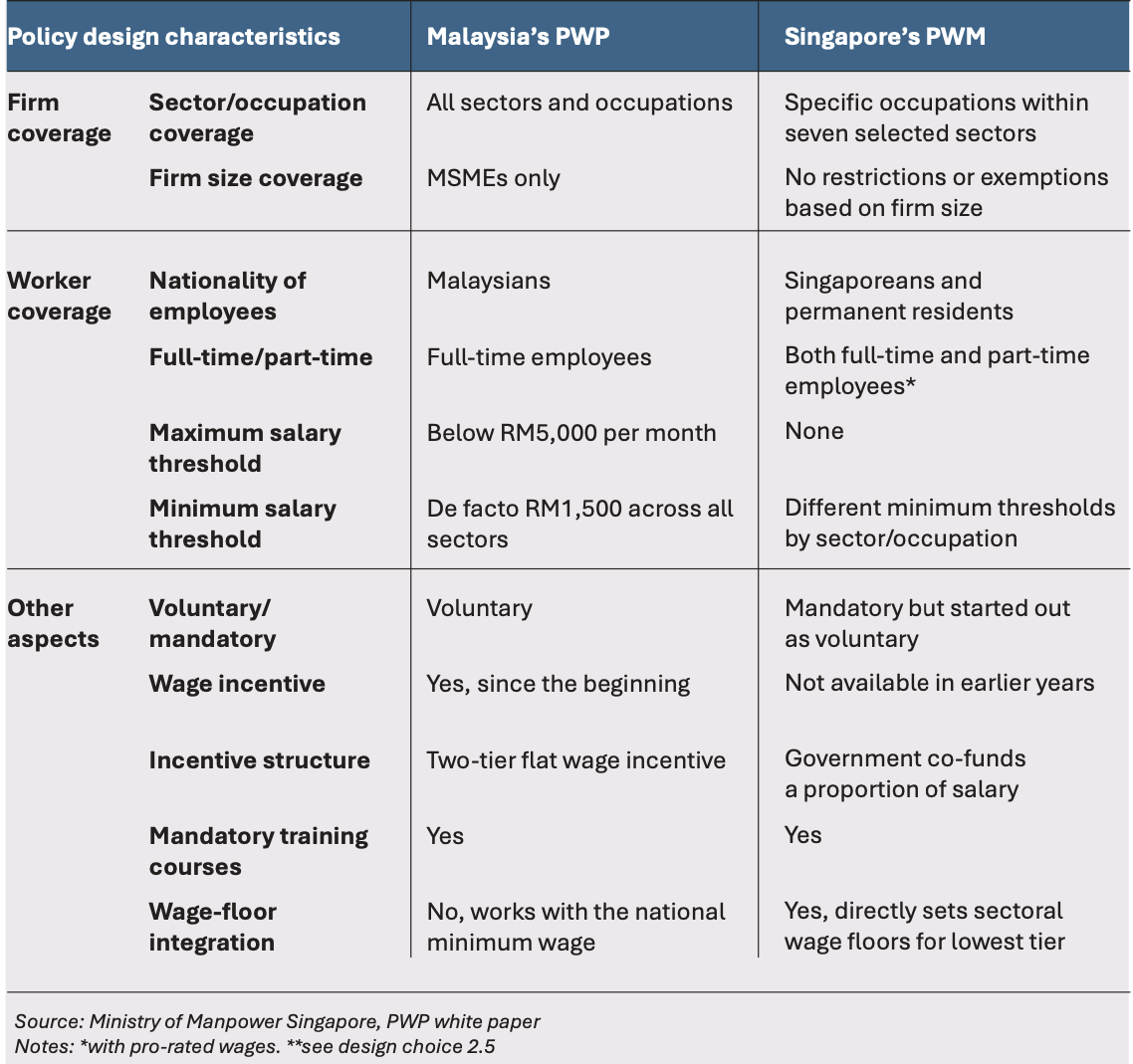

Singapore’s Progressive Wage Model was launched in 2014, in response to the challenge of rising income inequality and slow wage growth among lower-income workers during the early 2000s.6 At first glance, Malaysia’s PWP shares similar objectives of wage growth, increasing productivity and human capital accumulation. However, despite similar naming conventions and common objectives, there are substantial differences between the Malaysian and Singaporean versions of the policy (see Table 1). This is due to differing legislative and institutional environments, as well as different policy design approaches (see Section 2).

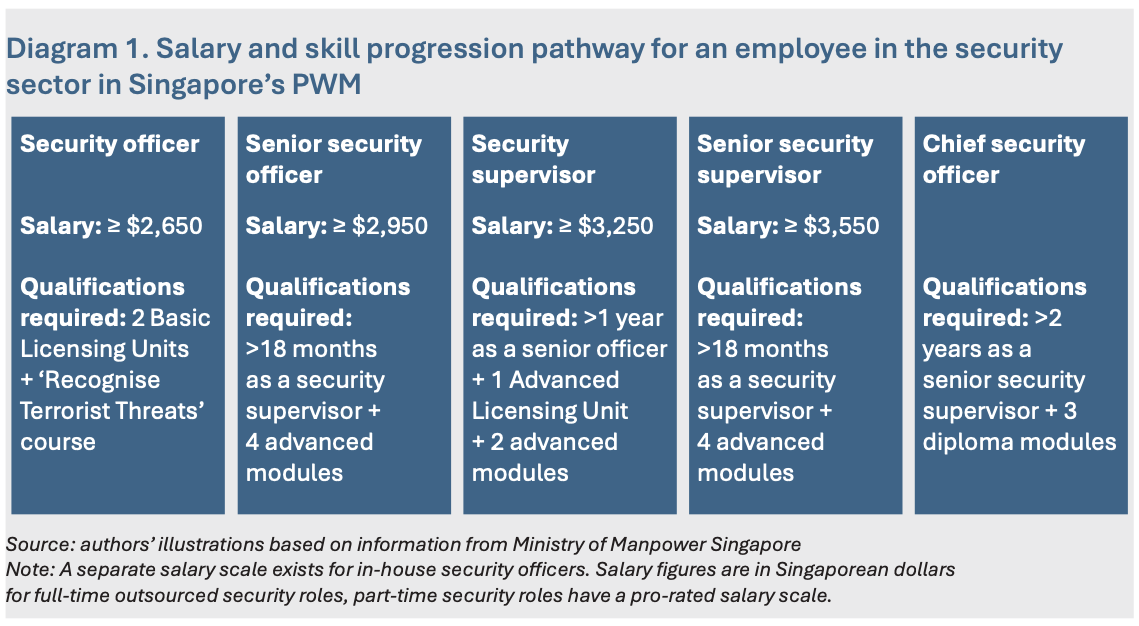

A key design difference is that Singapore’s model currently requires mandatory compliance for all firms within the seven sectors, while Malaysia’s approach is voluntary, covering all sectors but restricts eligibility to MSMEs.7 At its launch, Singapore’s PWM initially only targeted the cleaning sector but over the years, it has gradually expanded to include sectors, such as security, landscape, retail and food services. This sector-specific strategy is integrated with career progression ladders for each occupation (see Diagram 1), establishing wage floors at each tier based on employees’ experience, along with required training qualifications. Likewise, there are also differences in worker and firm eligibility, with Singapore’s PWM covering all firms regardless of size, as well as both full-time and part-time workers (see Table 1).

Moreover, from an institutional perspective, another major difference is that Singapore does not have a statutory minimum wage. Instead, Singapore’s PWM sets starting wages for each covered sector and occupation through its PWM framework. As compliance is mandatory, the starting wages for the lowest tier in each sector effectively act as a de facto sectoral wage floor. This contrasts with Malaysia’s PWP, which works on top of the RM1,500 national minimum wage.

Table 1: Key design aspects of progressive wage policies in Malaysia and Singapore

2. Understanding PWP policy design choices and challenges

Policy design matters because even small design decisions can have significant impacts on incentive structures and ultimately, how well a policy works in practice. This section explores the different policy design options available for the PWP and highlights the implications and challenges of these decisions. This section aims to lay out a list of design considerations, setting the stage for specific policy recommendations in Section 3.

Design consideration 2.1: should participation be voluntary or mandatory?

A voluntary system will be less disruptive and make it easier for small businesses to adapt in the short term. Currently, Malaysia’s PWP allows employers to opt-in voluntarily, in contrast with the mandatory participation in Singapore’s Progressive Wage Model (PWM). This aims to reduce compliance burdens for firms, particularly for microenterprises already contending with the recent minimum wage increases.8 This approach has the benefit of allowing for a more gradual adaptation process for firms, mitigating any broader general equilibrium impact on employment and/or inflation, as well as making it easier to evaluate the pilot by limiting the number of participating firms.

But in the long term, a voluntary PWP may limit its wage and productivity impacts. Singapore’s experience with its PWM indicated that firm participation rates were low until the scheme was made mandatory, suggesting that Malaysia’s PWP is likely to face a similar challenge.9 Firms will be reluctant to incur to the upfront costs of wage increases and training without clear immediate returns. Further, without sufficient subsidies, the financial burden could render participating firms less competitive in the short term.

This could create a collective action problem, trapping firms in a status quo that hinders higher productivity and wages. A voluntary approach could also lead to a self-selection bias where only well- resourced, higher-productivity MSMEs will opt in, while workers in lower-productivity MSMEs or sectors are left out. This may exacerbate existing power imbalances between employers and workers, especially in the context of Malaysia where collective bargaining is limited.1011 Overall, a voluntary PWP will offer flexibility and reduce compliance burdens on firms but also poses risks of low participation and higher inequality.

Design consideration 2.2: who/which workers and firms will be covered?

PWP’s current coverage could exclude most workers in Malaysia. The PWP pilot phase only targets full-time employees – leaving part-time, informal workers and other non-standard workers (such as those with a contract for service under three years) outside its coverage. This contrasts with Singapore’s PWM, which includes full-time and part-time employees. Likewise, Malaysia’s PWP only includes MSMEs, compared with Singapore’s PWM, which includes firms of all sizes.

This combination of firm and worker eligibility will have a significant impact on the inclusiveness of Malaysia’s PWP. Notably, less than half of all workers in Malaysia are employed by MSMEs.12 While the white paper notes that two-thirds of the workforce falls below the RM5,000 maximum participation threshold – our back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that adding further eligibility conditions like, including only MSMEs13 and full-time workers, will bring coverage down to less than 31% of workers.14 The voluntary nature in the current iteration of the PWP will further reduce this proportion significantly. Further assuming a 50% participation rate among MSMEs and making simplifying assumptions on the distribution of employment and selection effects, means that only 1 in 5 workers is included in PWP.

Coverage choice and by extension, inclusiveness of PWP, will have significant effects on programme impacts, costs and implementation. Generally, choosing to cover a higher proportion of workers will mean greater programme impacts on raising wages, productivity and skills. This will also mitigate risks of widening divisions between more and less secure forms of employment as well as between MSMEs and larger firms – both of which are real risks of targeting policy on specific subgroups (discussed further in policy recommendation 3.2). However, greater coverage and inclusiveness also carry important considerations. Broadening the PWP’s scope to cover a higher proportion of worker types could increase administrative complexity, raise costs and make it harder to implement and enforce, especially if institutional capacity or fiscal commitments are limited.

Design consideration 2.3: how should PWP work with existing skills training ecosystem?

The ability of PWP to drive greater human capital development and productivity depends on the efficacy of Malaysia’s existing skills training ecosystem. Currently, a large gap exists between workers’ demand for skills training (97% of Malaysian employees report wanting skills training) and actual provision (only 36% report receiving it).15 This disparity highlights an opportunity for PWP to bridge this gap by incentivising employers to offer greater support in the training and development of their employees. However, the current levy system – which revolves around the Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF) collected from registered companies and then disbursed as training grants – faces numerous challenges.

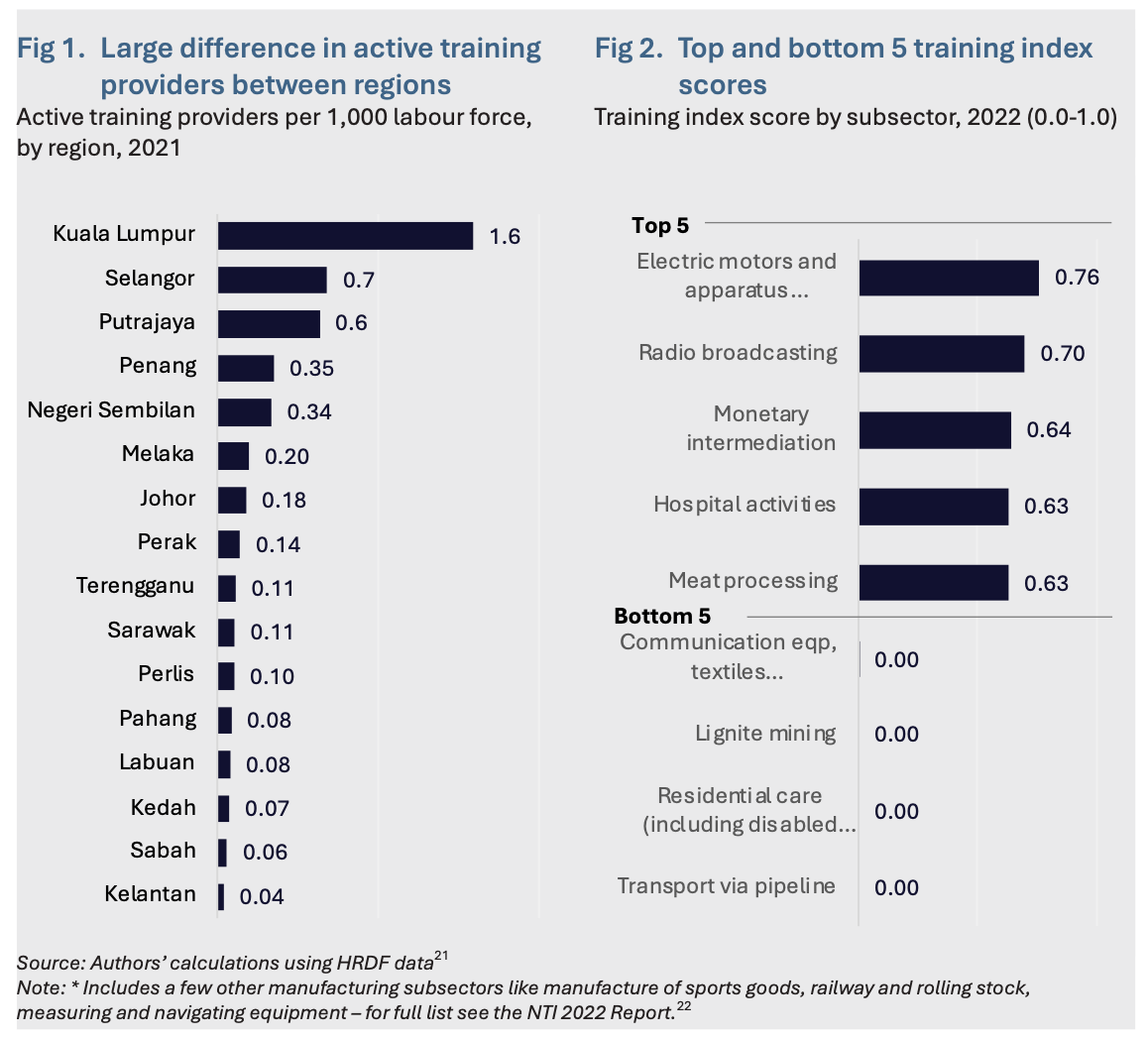

Malaysia’s existing skills training ecosystem faces supply-side, demand-side and governance challenges. On the supply side, the density of training providers and availability of programmes vary significantly by region. For instance, HRD Corp data indicates that in Kuala Lumpur, there are about 1.6 active training providers per 1,000 labour force, whereas Kelantan only has 0.04 per 1,000 (Figure 1). This, alongside reported limitations16 in the quality of specialised training providers, contributes to huge differences17 in the percentage of employees who receive training by sub-sector (Figure 2) and consequently the utilisation of the HRDF levy across industries.18

On the demand side, other barriers include a low levy balance for many MSMEs (a weakness of the current levy system) and information gaps regarding the availability of training courses.19 Additionally, many workers cite high workload and time constraints as obstacles to accessing training programmes, underscoring the need for greater employer support. Finally, PWP’s success will depend on addressing governance issues within the HRD Corp-driven skills ecosystem, including past incidents of misappropriation, mismanagement and fraud related to training credits.20

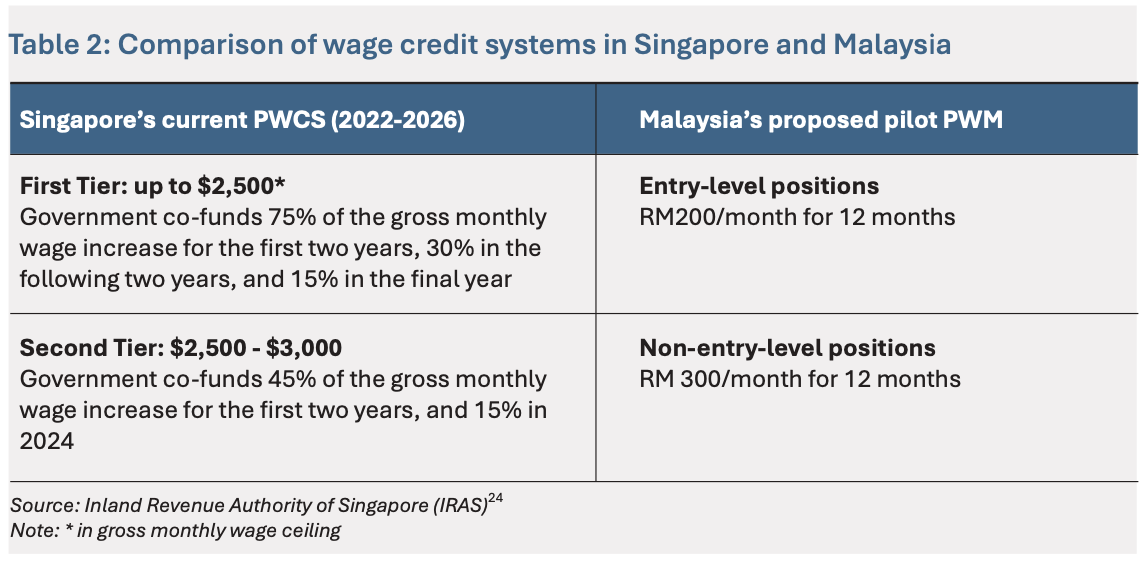

Design consideration 2.4: how should the wage subsidy/incentive system work?

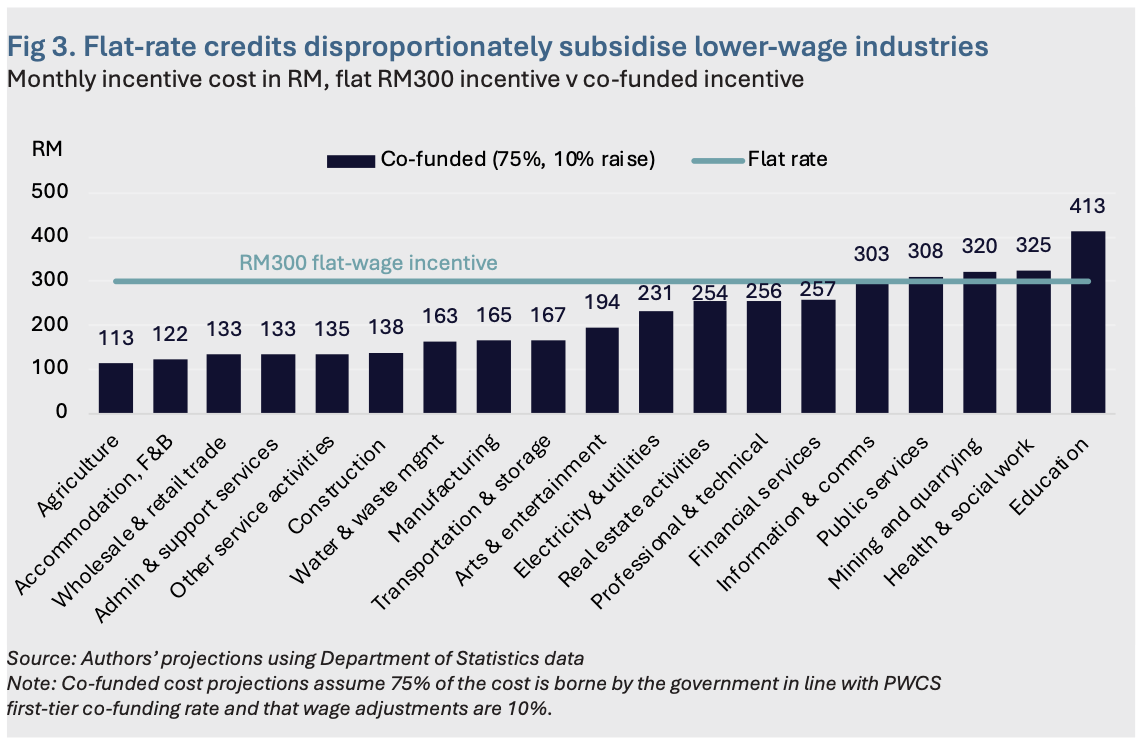

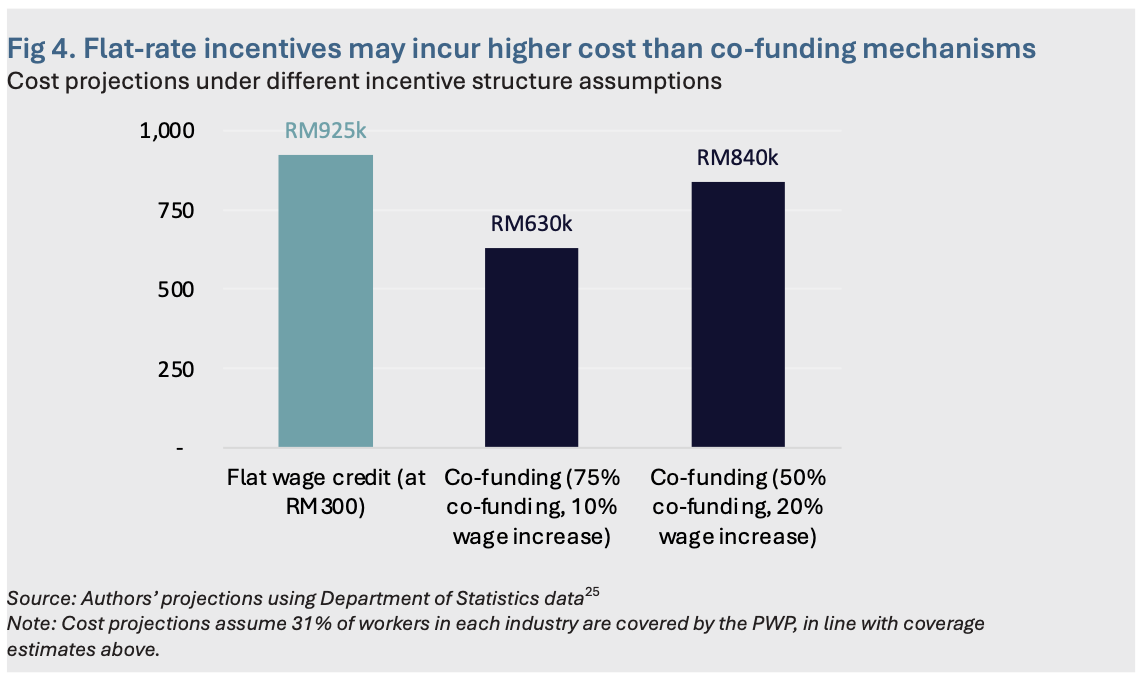

Malaysia’s flat-wage incentive is easier to implement but would also subsidise lower-wage sectors more heavily. A flat-wage-incentive system requires less administrative capacity and is simpler for small businesses to comply with. However, evaluated against a backdrop of large differences between wages across regions and industries in Malaysia, a flat incentive could result in the incentive being overly generous for some firms and insufficient for others (Figure 3). This disproportionately benefits lower- wage sectors over higher-wage sectors and could compress wage differentials between industries, occupations and skill levels. Although this approach might reduce wage inequality in the short term, subsidising lower-wage, lower-productivity sectors more heavily relative to higher-productivity sectors could distort market incentives for productivity improvement, in turn undermining longer-term structural transformation and economic growth.

A tiered co-funding model like Singapore’s will involve greater administrative complexity but could offer a more flexible approach. A co-funding model would be harder to implement but could align incentives more closely with the varying wage levels across different sectors and regions. Additionally, depending on the suggested wage guidelines and amount of co-funding, a flat incentive approach may also entail higher outlays compared with a co-funding mechanism (Figure 4). As such, the choice of which wage credit modality to use for Malaysia’s PWP in the future will depends on its long-term policy priorities.

Design consideration 2.5: how will PWP salary increase guidelines align with skill progression pathways?

Singapore’s PWM suggests that aligning salary increase guidelines with tailored skill pathways for each occupational tier could improve career progression clarity. Singapore sets detailed requirements for training programmes in each sector and each occupational tier, tailored to the skill requirements in different industries (see Diagram 1 for an example).26 For instance, under the Singaporean model, a security officer will need to complete four advanced security-related modules, and have at least 18 months’ experience, before being considered for progression to a senior security officer position. Aligning wage progression with an occupation-specific skills acquisition pathway offers workers a better understanding of what types of training will advance their productivity and career, instead of arbitrarily selecting courses just to meet the training criteria.

Currently, there is no indication that the salary increase guidelines in Malaysia’s PWP will be aligned to a skill progression pathway. While there is mention of a working committee that will produce an annual wage guide for each industry, the white paper stops short of detailing the implementation of skills progression pathways.27 This raises important considerations about how required skills training will align with the wage-increment ladder. Foregoing occupation-specific skill progression and career pathways will certainly simplify programme administration and ease the PWP’s implementation across all economic sectors. However, clearly defined skills progression is crucial for structuring the types of skill training appropriate for each sector and job role.

Design consideration 2.6: potential effects on labour costs and other unintended negative effects

Implementation of PWP could lead to a rise in labour costs, which, in turn, could have knock- on effects on the economy. Standard economic theory suggests that firms can respond to potential cost increases by adjusting on several different margins.28 This is especially important if the PWP- mandated wage increases are not compensated by corresponding productivity gains. They could either reduce their labour demand (and thus employment) – which will be more likely in cost-sensitive goods- producing industries facing greater price competition from abroad.

Alternatively, they could absorb cost increases by reducing profit margins or by increasing prices. Fortunately, empirical evidence from the minimum wage literature indicates that broadly, labour demand elasticities are modest, with firms tending to respond by increasing prices and reducing profit margins rather than by cutting employment.29 Nonetheless, this can vary tremendously across sectors, with goods-producing sectors more likely to be affected. While the scenario analysis in the white paper predicts modest price impacts (only about half a percentage point increase in inflation)30 , this analysis does not estimate labour demand elasticities nor does it consider differential impacts across sectors and firms.

These risks may raise a few important considerations for the implementation of Malaysia’s PWP. The first is the potential risk of knock-on impacts on more cost-sensitive sectors, particularly in lower- cost manufacturing sub-sectors that cannot easily substitute labour-saving technologies. The second is that there may be a short-term trade-off between the size and breadth of PWP and the potential risks of unintended economic consequences on employment and/or prices. Consequently, policymakers should ensure the PWP’s design mitigates these risks while accommodating sector-specific needs. Additionally, it is essential to put into perspective how the long-term benefits in productivity, wages and worker welfare would outweigh these short-term risks.

3. Policy recommendations

3.1 Make a phased transition from voluntary to mandatory participation

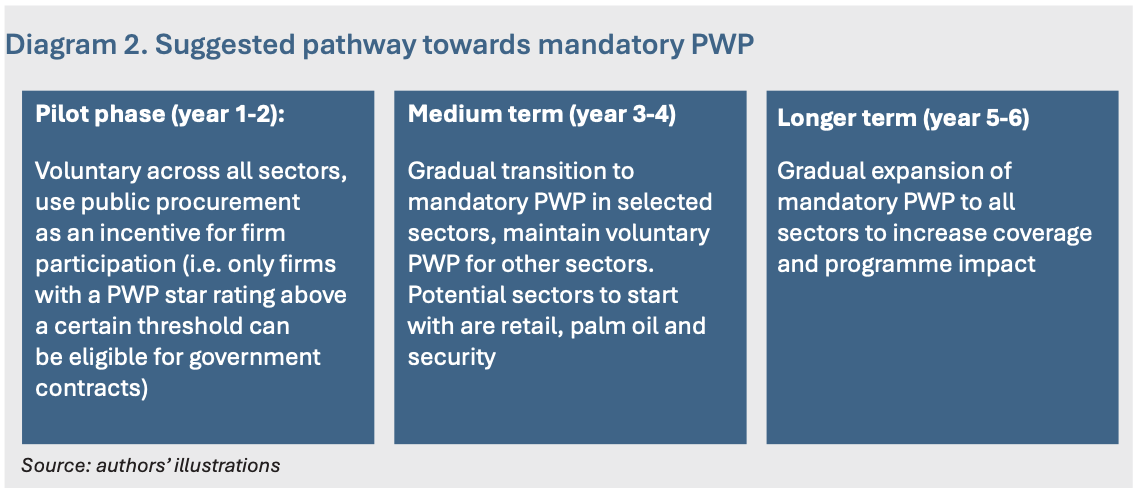

This gradual transition towards a mandatory PWP will strengthen its ability to increase wages and skills development, while mitigating the potentially disruptive effects it could have on MSMEs. On this front, Malaysian policymakers can use Singapore’s sectoral transition to mandatory compliance as a case study.31 In its first year of implementation for the cleaning sector in 2014, Singapore’s PWM was voluntary, with mandatory compliance gradually phased in.

While most firms were exempted from the PWM’s mandatory salary requirements in the first year of implementation, compliance with the wage guide was required for firms seeking to tender for or were already awarded public-sector contracts.32 This gradual phase-in approach allowed firms to adapt to the salary requirements as they explored other avenues to reduce costs and increase revenue, while maintaining incentives for firms to eventually comply with PWM standards. This allowed policymakers to learn from the gradual rollout, allowing them to refine its policy design before it was expanded nationwide.

As such, Malaysia’s PWP could outline a phased transition plan, using a sector-specific approach towards the expansion of mandatory compliance (Diagram 2). In the shorter term during the pilot phase, policymakers should use access to public contracts as an incentive towards participation – for example, by requiring firms to retain a minimum “Progressive Wage Employers” star rating as outlined in the white paper.33 In the medium to longer term, Malaysian policymakers could start by implementing mandatory PWP for selected lower-wage priority sectors and occupations, such as frontline retail and hospitality, security and palm oil sectors. Considering that GLCs and government agencies have significant presence in retail, hospitality and palm oil production, using public contracts as a tool could play an outsized role in expanding mandatory PWP in these sectors.

3.2 Gradually broaden the PWP’s coverage of workers and firms

Broadening PWP coverage will boost its impacts on wages, productivity and skills, while reducing disparities between more- and less-secure forms of employment (see design choice 2.2). In the long term, excluding informal and part-time workers from wage and skill development opportunities could result in a widening productivity gap and make it harder for these workers to move into full-time positions.

At the same time, it is important to recognise that there remains a significant share of low-wage and entry-level positions even within larger firms and multinational corporations, underpinning the need for equal coverage of workers in the same occupation regardless of firm size. To this end, policymakers should adopt a phased approach to broadening coverage in tandem with the transition towards mandatory participation (outlined in recommendation 3.1). This will allow gradual extension of PWP to cover more workers, allow firms time to adapt and enable continuous policy refinement based on tripartite feedback.

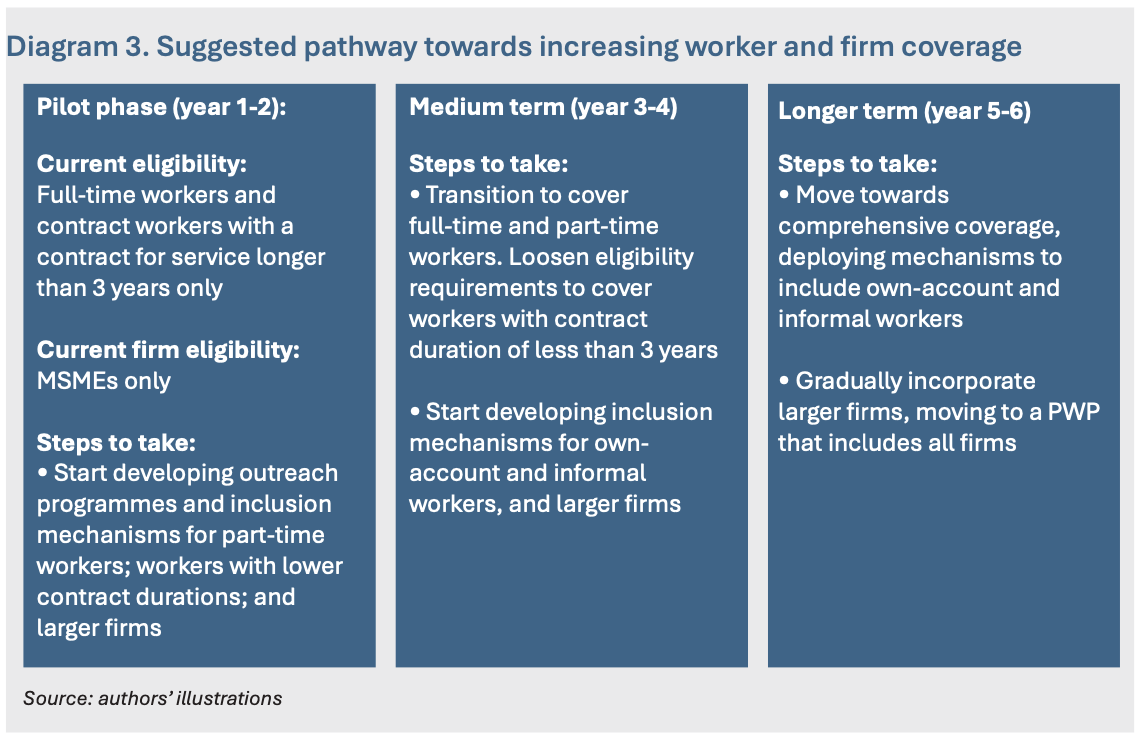

This phased approach would mean widening the eligibility conditions for PWP participation. In the pilot phase, policymakers should start developing outreach programmes and inclusion mechanisms towards eventually comprehensive coverage of workers with shorter contract duration below three years (for workers bound under a contract for service) and part-time workers (Diagram 3). In the medium term, policymakers could begin a transition to cover both full-time and part-time workers in line with Singapore’s model, while gradually loosening contract eligibility conditions to less than three years.

At the same time, policymakers should start developing steps to include other own-account and informal workers and broaden firm coverage to larger firms. In the longer term, PWP can move towards comprehensive coverage across more diverse worker types and all firms regardless of size. This may entail special PWP programmes for self-employed and gig workers that offer direct subsidies for training and skills development.

3.3 Ensure PWP is accompanied by ongoing efforts to strengthen labour-market institutions and standards

In the implementation of PWP, policymakers need to ensure that this does not detract from ongoing efforts to strengthen labour market institutions and standards. Recent discussions that position the current voluntary version of PWP (see design choice 2.1 and policy recommendation 3.1) as a potential substitute for the mandatory minimum wage raise concerns about the weakening of labour protections for the country’s most vulnerable workers.34 Such a shift could threaten to reverse years of progress towards a higher-wage, higher-productivity economic equilibrium and could affect both wage growth and Malaysia’s long-term growth prospects.35

On this front, policy messaging and communication should clearly outline that PWP will not affect the continued existence of a mandatory wage floor that is enforced for all firm sizes and sectors. Similarly, there is a need to assure stakeholders that the introduction of PWP will not affect the biennial minimum wage review process mandated through the National Wages Consultative Council as established by the 2011 National Wages Consultative Council Act (Act 732). The statutory wage floor should remain an independent standard set with recommendations from the council, with the PWP only guiding additional wage progression above the mandatory wage floor.

3.4 Establish greater integration with existing skills policies and institutions

The PWP white paper does not detail how the programme will be integrated with the existing skills training ecosystem, educational pathways or active labour market policies. Strengthening these links will increase its effectiveness and streamline implementation.

- Establishing a PWP skill progression pathway via HRD Corp: Policymakers should leverage on HRD Corp’s existing data and expertise to pinpoint sector-specific skill requirements and outline well- defined skill and career progression pathways. These pathways should detail the necessary skill acquisition and training for each sector and occupation, aligned with the PWP salary increase guidelines (see Design consideration 2.5 and Diagram 1). This would ensure that PWP-mandated wage increases are aligned with skills attainment for each level. Greater integration with HRD Corp courses, including its Micro-credential Initiative, will ensure that there is a clear skills progression that aligns with industry demand and provides workers with verifiable qualifications that signal their skill levels.

- Integration with TVET, AiI and alternative higher-education pathways: Closer integration between the proposed PWP and existing institutions in the alternative higher-education system, such as TVET and AiI, can help align early career training with the PWP’s goals. This could entail aligning the TVET/ AiI curriculum with the skill requirements and progression pathways identified for each industry. Similarly, this could include a system where skills and certifications obtained through TVET/AiI are credited within the PWP framework, as in the Recognition of Prior Experiential Learning (RPEL) programme.36

3.5 Strengthen existing skills development and training ecosystem

As outlined in Design consideration 2.4, a crucial aspect of maximising PWP’s ability to meet its goals lies in enhancing the accessibility, quality and governance of the existing skills development and training ecosystem. On the former, access to the existing skills training ecosystem could be improved by reducing financial/information barriers to Skim Bantuan Latihan (SBL) participation and broadening access beyond HRDF-registered employers, such as through expanding existing SCOPE/e-LATiH programmes. Additionally, this could entail increasing the allowable training cost and/or available training grants for sectors for which training programmes tend to be expensive, or for firms/sectors where levy balances are low, such as due to the recent 2021 expansion of the PSMB Act 2001.37

Further, improving the quality and relevance of training could come from increasing the trainer pool while expanding training options. Policymakers could accelerate the Train-the-Trainers programmes (and HRD-TDF)38, allowing more foreign trainers by relaxing SBL-approval requirements and expanding options for on-the-job training support. Lastly, there is a need to address long-standing governance issues within the HRD Corp ecosystem, including past misappropriation of funds and “training credit scams”.39 This can entail learning from Singapore’s experience in deploying fraud analytics to address incidents related to false training claims.40

3.6 Reduce compliance and documentation burden for small firms and microenterprises to boost participation

One concern with the PWP framework is that there may be high compliance and administrative burdens for the smallest and least capable firms. This could increase their operational costs and discourage their participation in PWP. To this end, policymakers could simplify reporting and compliance procedures, making it easier to report and receive verification for employees’ wage increases and skills training attended. This could include using standardised mobile-friendly platforms, such as through the planned PADU app.

Additionally, policymakers could implement a compliance-assistance programme specifically for microenterprises. This would provide the necessary technical and monetary support to help bridge gaps microenterprises face related to compliance and reporting.

3.7 Ensure pilot programme is useful for policy refinement and impact evaluation

It is important to ensure that the PWP’s pilot is fruitful and productive. The pilot phase is a critical opportunity to test, learn and adapt PWP to ensure its effectiveness and sustainability when rolled out on a larger scale – and as such it needs to provide valid information about the impacts, benefits and weaknesses of the proposed PWP. As such, policymakers should take relevant steps to make the pilot programme’s evaluation internally and externally valid.

From an internal validity standpoint, policymakers need to ensure that the experimental design of the pilot programme is rigorous to accurately link observed impacts on PWP. This will involve effective randomisation, building comparable control groups and implementing rigorous monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. In terms of external validity, the pilot programme needs to include a diverse and representative sample of firms – encompassing different sizes, sectors and regions. The current strategy of choosing 1,000 firms voluntarily will create challenges in ensuring that the results of the pilot are generalisable to the broader economy and limit the ability of policymakers to draw actionable insights into PWP’s impact.

- Conclusion

Malaysia’s PWP presents an innovative approach to improving wages, productivity and skills development, which will become increasingly urgent as it navigates a transition towards a high-income economy. As the policy moves from its pilot to wider national implementation, careful consideration must be given to its policy design choices, particularly surrounding voluntary versus mandatory participation, coverage and inclusivity, and its integration with wider skills development ecosystems. In the longer term, broadening worker and firm coverage, and gradually transitioning towards a mandatory approach could increase the programme’s impacts.

Endnotes

- Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf - The Star. (2023, 14 December). Towards a progressive wage policy.

https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/12/14/towards-a-progressive-wage-policy - Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf - Ibid.

- Choy, N.Y., & Tay, C. (2023, 30 November). Progressive wage to cover those with RM1,500- RM4,999 monthly salary, MNCs, GLCs exempted, White Paper proposes. The Edge Malaysia.

https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/692117 - Poh, J. (2007). Workfare: The fourth pillar of social security in Singapore, Ethos Working Paper number 3. Available at

https://knowledge.csc.gov.sg/ethos-issue-03/ - Ministry of Manpower Singapore. What is PWM?

https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/what-is-pwm - Tay, C. (2023, 11 December). The State of the Nation: Progressive Wage Policy: What we know and don’t know so far. The Edge Malaysia.

https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/692668 - Sapari, Z. (2019, 9 December). My Real Champions. Labourbeat.

https://www.labourbeat.org/opinions/zainal-sapari-my-real-champions/ - Ng, Y.H. (2023, 20 January) A labour agenda for Malaysia. New Mandala.

https://www.newmandala.org/a-labour-agenda-for-malaysia/ - Muthusamy, N. & Wikstrom, E. (2022). Wages as Power: Models of Institutionalised Wage Bargaining and Implications for Malaysia. Khazanah Research Institute.

https://www.krinstitute.org/assets/contentMS/img/template/editor/WORKING%20PAPER%20–%20IWBs_vFinal2.pdf - The Star. (2023, 27 July). Malaysia’s MSME GDP surges 11.6% in 2022 to RM580.4bil -DOSM.

https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2023/07/27/malaysia039s-msme-gdp-surges-116-in-2022-to-rm5804bil–dosm - HR Asia. (2023, 2 November). Improvements in labour market by Malaysian SMEs: SME CEO Forum 2023.

https://hr.asia/hr-asia/improvements-in-labour-market-by-malaysian-smes-sme-ceo-forum-2023/#:~:text=The%20SMEs%20employ%20a%20total,Malaysia%20is%20provided%20b%20SMEs - This estimate is calculated by multiplying the fraction of MSME employment in 2022 (48.2% –from DOSM SME statistics) with the average proportion of full-time workers in 2022 (97.9% – from Labour Force Survey data) and number of workers with a monthly salary of below RM5,000 (66.6% – figure from the PWP white paper)

- (2022). 97% of Malaysians are interested in learning and development opportunities, but only 36% received them: workmonitor.

https://www.randstad.com.my/hr-trends/workforce-trends/malaysians-interested-in-learning-and-development-opportunities/ - Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF). (2019). Industrial insights report Issue: 1/2019.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/1.-HRDF_Insights_Report_Issue01_2019.pdf - Human Resources Development Corporation (HRD Corp). (2021). Industrial insights report: Issue 3/2021.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/8.-HRD-Corp_Insights_Report_ Issue03_2021.pdf - HRD Corp. (2022). Industry training participation report: 2021 edition.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/HRDCorp_Industry_Training_Participation_Report_2021.pdf - HRD Corp. (2023). National Training Index report 2022

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/download/57307/?tmstv=1694162353 - (2022). 97% of Malaysians are interested in learning and development opportunities, but only 36% received them: workmonitor.

https://www.randstad.com.my/hr-trends/workforce-trends/malaysians-interested-in-learning-and-development-opportunities/ - HRD Corp. (2021). Training Supply in Malaysia. 1/2021.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/13_2021_Industrial_Intelligence_Report.pdf - HRD Corp. (2023). National Training Index report 2022

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/download/57307/?tmstv=1694162353 - Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Progressive Wage Credit Scheme (PWCS).

https://www.iras.gov.sg/schemes/disbursement-schemes/progressive-wage-credit-scheme - Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Progressive Wage Credit Scheme (PWCS).

https://www.iras.gov.sg/schemes/disbursement-schemes/progressive-wage-credit-scheme - Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (2023). Salaries and Wages Survey Report 2022.

https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/salaries-and-wages-survey-report-2022 - Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Occupational Progressive Wages for administrators and drivers.

https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/occupational-pws-for-administrators-and-drivers - Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf - Devicienti, F. & Fanfani, B. (2021, July). Firms’ Margins of Adjustment to Wage Growth: The Case of Italian Collective Bargaining. IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Discussion Paper No. 14532.

https://docs.iza.org/dp14532.pdf - Harasztosi, P. & Lindner, A. (2019). Who Pays for the Minimum Wage? American Economic Review, 109 (8): 2693-2727. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20171445; Dube, A., Lester, T. W., & Reich, M. (2010). Minimum wage effects across state borders: estimates using contiguous counties. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 945–964.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40985804 - Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf - Yuen, S. (2018). Parliament: Progressive wage models can be extended to more sectors, says Sam Tan. The Straits Times.

https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-progressive-wage-models-can-be-extended-to-more-sectors-sam-tan - Ministry of Manpower Singapore. What is PWM?

https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/what-is-pwm - Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf - The Star. (2023, 30 November). No minimum wage order following progressive wages, says Economy Minister.

https://www.thestartv.com/v/no-minimum-wage-order-following-progressive-wages-says-economy-minister

Syazmeena, E. (2023). PSM leader raises concerns over Rafizi’s PWP proposal. Focus Malaysia.

https://focusmalaysia.my/psm-leader-raises-concerns-over-rafizis-pwp-proposal/ - Cheng, C. (2023). Post-Covid-19 recovery and the quest for ‘good jobs. In M.H. Lee & A. Mahadi (Eds.), Where do we go workwise? Malaysia’s Labour landscape (pp.31-52). TalentCorp.

https://www.isis.org.my/2023/11/01/post-covid-19-recovery-and-quest-for-good-jobs/ - HRD Corp. Recognition of Prior Experiential Learning (RPEL).

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/rpel - HRD Corp. Pembangunan Sumber Manusia Berhad Act 2001.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/psmb-act-2001 - HRD Corp. HRD Corp Trainers’ Development Framework (HRD-TDF) Implementation Guideline.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Guidelines_of_HRD-TDF_2022.pdf - Aiman, A. (2018,10 November). No more 30% pool fund in HRDF. Free Malaysia Today.

https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2018/11/10/no-more-30-pool-fund-in-hrdf/ - Mahfar, R. (2022, 30 June). More work needs to be done on HRD Corp’s micro-credential initiative. The Malaysian Reserve.

https://themalaysianreserve.com/2022/06/30/more-work-needs-to-be-done-on-hrd-corps-micro-credential-initiative/

References

Aiman, A. (2018, 10 November). No more 30% pool fund in HRDF. Free Malaysia Today.

https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2018/11/10/no-more-30-pool-fund-in-hrdf/

Cheng, C. (2023). Post-Covid-19 recovery and the quest for ‘good jobs. In M.H. Lee & A. Mahadi (Eds.), Where do we go workwise? Malaysia’s Labour landscape (pp.31-52). TalentCorp.

https://www.isis.org.my/2023/11/01/post-covid-19-recovery-and-quest-for-good-jobs/

Choy, N.Y., & Tay, C. (2023, 30 November). Progressive wage to cover those with RM1,500-RM4,999 monthly salary, MNCs, GLCs exempted, White Paper proposes. The Edge Malaysia.

https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/692117

Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (2023). Salaries and Wages Survey Report 2022.

https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/salaries-and-wages-survey-report-2022

Devicienti, F. & Fanfani, B. (July 2021). Firms’ Margins of Adjustment to Wage Growth: The Case of Italian Collective Bargaining. IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Discussion Paper No. 14532.

https://docs.iza.org/dp14532.pdf

Dube, A., Lester, T. W., & Reich, M. (2010). Minimum wage effects across state borders: estimates using contiguous counties. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 945–964.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40985804

Harasztosi, P. & Lindner, A. (2019). Who Pays for the Minimum Wage? American Economic Review, 109 (8): 2693-2727. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20171445

HR Asia. (2 November 2023). Improvements in labour market by Malaysian SMEs: SME CEO Forum 2023.

https://hr.asia/hr-asia/improvements-in-labour-market-by-malaysian-smes-sme-ceo-forum-2023/#:~:text=The%20SMEs%20employ%20a%20total,Malaysia%20is%20provided%20by%20SMEs

Human Resources Development Corporation (HRD Corp). (2021). Industrial insights report: Issue 3/2021.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/8.-HRD-Corp_Insights_Report_Issue03_2021.pdf

HRD Corp. (2022). Industry training participation report: 2021 edition.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/HRDCorp_Industry_Training_Participation_Report_2021.pdf

HRD Corp. (2021). Training Supply in Malaysia. No. 1/2021.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/13_2021_Industrial_Intelligence_Report.pdf

HRD Corp. (2023). National Training Index report 2022

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/download/57307/?tmstv=1694162353

HRD Corp. HRD Corp Trainers’ Development Framework (HRD-TDF) Implementation Guideline.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Guidelines_of_HRD-TDF_2022.pdf

HRD Corp. Pembangunan Sumber Manusia Berhad Act 2001.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/psmb-act-2001

HRD Corp. Recognition of Prior Experiential Learning (RPEL).

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/rpel

Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF). (2019). Industrial insights report. Issue: 1/2019.

https://hrdcorp.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/1.-HRDF_Insights_Report_Issue01_2019.pdf

Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Occupational Progressive Wages for administrators and drivers.

https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/occupational-pws-for-administrators-and-drivers

Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. Progressive Wage Credit Scheme (PWCS).

https://www.iras.gov.sg/schemes/disbursement-schemes/progressive-wage-credit-scheme

Kementerian Ekonomi. (2023). Kertas Putih Cadangan Dasar Gaji Progresif.

https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/sites/default/files/2023-11/Kertas_Putih_Cadangan_Dasar_Gaji_Progresif.pdf

Mahfar, R. (2022, 30 June). More work needs to be done on HRD Corp’s micro-credential initiative. The Malaysian Reserve.

https://themalaysianreserve.com/2022/06/30/more-work-needs-to-be-done-on-hrd-corps-micro-credential-initiative/

Ministry of Manpower Singapore. What is PWM?

https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/progressive-wage-model/what-is-pwm

Muthusamy, N. & Wikstrom, E. (2022). Wages as Power: Models of Institutionalised Wage Bargaining and Implications for Malaysia. Khazanah Research Institute.

https://www.krinstitute.org/assets/contentMS/img/template/editor/WORKING%20PAPER%20–%20IWBs_vFinal2.pdf

Ng, Y.H. (2023, 20 January) A labour agenda for Malaysia. New Mandala.

https://www.newmandala.org/a-labour-agenda-for-malaysia/

Poh, J. (2007). Workfare: The fourth pillar of social security in Singapore, Ethos Working Paper number 3.

https://knowledge.csc.gov.sg/ethos-issue-03/

Randstad. (2022). 97% of Malaysians are interested in learning and development opportunities, but only 36% received them: workmonitor.

https://www.randstad.com.my/hr-trends/workforce-trends/malaysians-interested-in-learning-and-development-opportunities/

Sapari, Z. (2019, 19 December). My Real Champions. Labourbeat.

https://www.labourbeat.org/opinions/zainal-sapari-my-real-champions/

Syazmeena, E. (2023). PSM leader raises concerns over Rafizi’s PWP proposal. Focus Malaysia.

https://focusmalaysia.my/psm-leader-raises-concerns-over-rafizis-pwp-proposal/

Tay, C. (2023, 11 December). The State of the Nation: Progressive Wage Policy: What we know and don’t know so far. The Edge Malaysia.

https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/692668

The Star. (2023, 14 December). Towards a progressive wage policy.

https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/12/14/towards-a-progressive-wage-policy

The Star. (2023, 27 July). Malaysia’s MSME GDP surges 11.6% in 2022 to RM580.4bil -DOSM.

https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2023/07/27/malaysia039s-msme-gdp-surges-116-in-2022-to-rm5804bil–dosm

The Star. (2023, 30 November). No minimum wage order following progressive wages, says Economy Minister.

https://www.thestartv.com/v/no-minimum-wage-order-following-progressive-wages-says-economy-minister;

Yuen, S. (2018). Parliament: Progressive wage models can be extended to more sectors, says Sam Tan. The Straits Times.

https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-progressive-wage-models-can-be-extended-to-more-sectors-sam-tan