Written by Lee Min Hui,Calvin Cheng Kah Weng, Shazana Agha and Anis Farid

With contributions from Prof Datuk Dr Norma Mansor, Dr Teoh Ai Hua and Sofea Azahar, May 2024

About the contributors

Lee Min Hui is a senior analyst in the Social Policy and National Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic & International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. Her research interests centre around issues of social inclusivity, primarily gender equality, welfare, care economy, aging, labour protections, urban poverty and planning. She holds a MA in Public Policy from King’s College London and a BA in Global in International and Global Studies from Monash University Malaysia.

Calvin Cheng is a fellow in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic & International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. His research interests span issues in applied economics, centring around jobs, social protection, economic development and the design of social transfer programmes. He holds a MSc in Public Policy from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and a BEcon in Economics and Econometrics from Monash University in Clayton.

Shazana Agha is currently head of research at Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO), a Malaysian non-profit organisation working to advance gender equality and end violence against women. Currently, she is a co-principal researcher for a research study focused on enhancing the resilience of care workers in Malaysia. She is also a strong advocate for a wide range of issues affecting women and girls in Malaysia. Shazana graduated from Monash University and holds a Master of Arts (Gender Studies) from University of Malaya.

Anis Farid is research project manager at Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO), overseeing the RE:CARE Project looking into building the resilience of the care workforce and infrastructure in Malaysia for future crisis-preparedness. In her current role, she is focused on women’s economic empowerment and the importance of recognising and addressing care work, both paid and unpaid. Anis holds a BA in Psychology from McGill University and a MSc in Social Policy from the London School of Economics.

Prof Datuk Dr Norma Mansor has been the director of the Social Wellbeing Research Centre since 2013. She has served as an adviser and consultant to various organisations, including the United Nations Development Programme, World Bank, International Labour Organisation, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, European Union, Asian Development Bank and numerous Malaysian public agencies. She is also the author of numerous books and journal articles on public and social policy, aging and social protection. She is a fellow of the Academy of Sciences Malaysia and president of the Malaysian Economic Association. She holds a PhD and a master’s from the University of Liverpool and a bachelor’s from Universiti Malaya.

Dr Teoh Ai Hua is a senior lecturer at the School of Applied Psychology, Social Work, and Policy, Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM). His research interests centre on public social services, professionalisation of social work, case management and care in the community. He also serves as the president of the Malaysian Association of Social Workers (MASW) and vice-president of the National Council on Welfare and Social Development Malaysia (MAKPEM). He holds a PhD in Social Work (UUM), an MA in Social Work Studies from the University of Kent at Canterbury and a bachelor’s in public administration from UUM.

Sofea Azahar is an analyst in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic & International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. Her research interests centre on development economics, with an emphasis on human capital development and the implications of educational inequality. She holds an MSc in Development Studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and a degree in Economics from the University of Essex.

Executive summary

- As Malaysia’s demographic transition deepens amid an aging society and a shrinking labour force, demand for care needs will surge, and its impacts will be felt most acutely by women who perform the bulk of unpaid care work. This creates an imperative for Malaysia to build a cradle-to-grave care economy that responds to care needs – encompassing child to elderly care and forms of specialised care like disabled or palliative care.

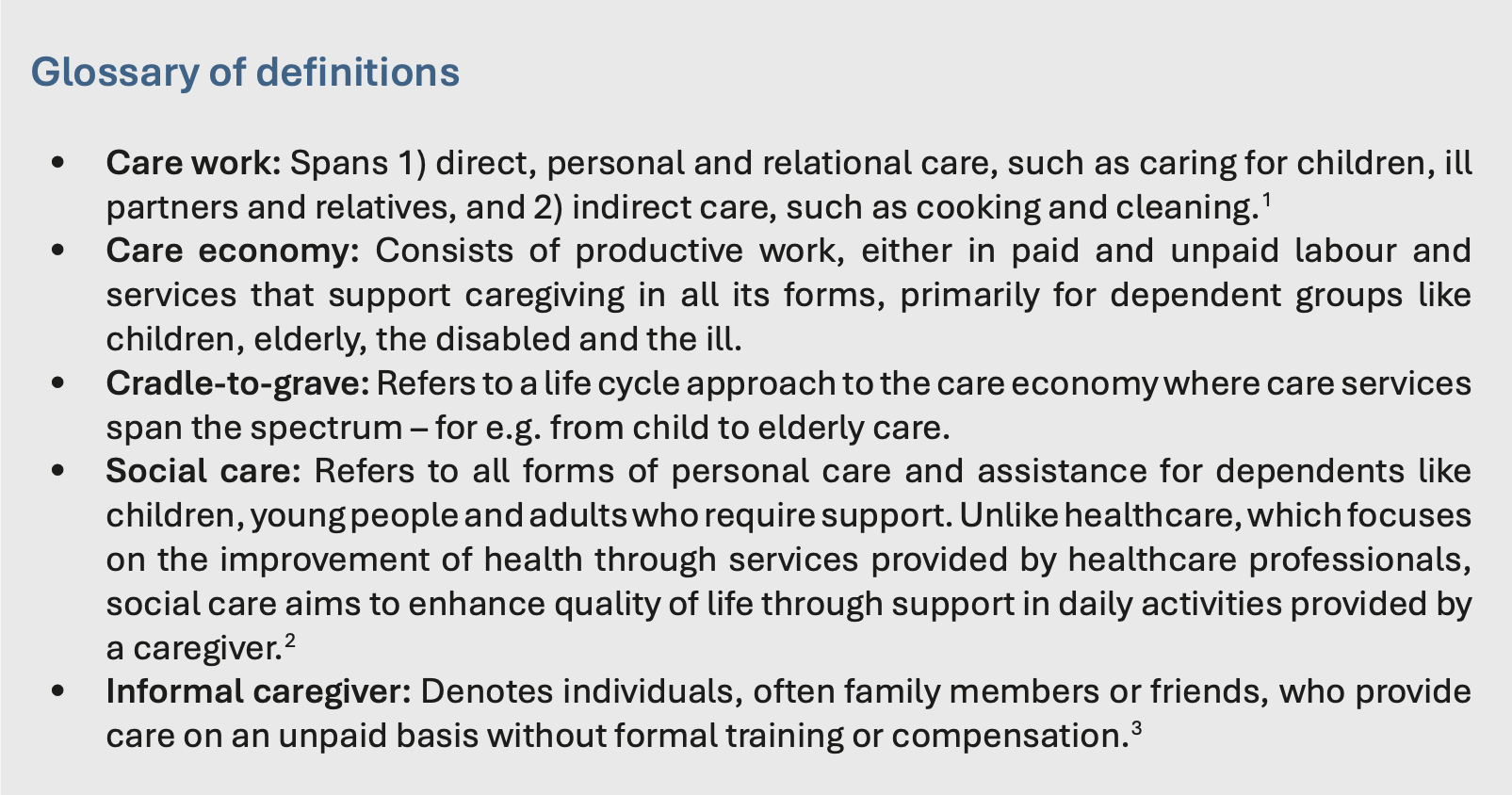

- The care economy is a potential driver of economic growth. If the unpaid care work produced in Malaysian homes every day could be valued in GDP figures, it would create about RM379 billion, accounting for a fifth of the service sector.

- By removing care constraints preventing participation in the labour force, Malaysia stands to enable 3.2 million workers to engage in paid employment and unlock 4.9 percentage points in GDP growth in 2022 alone.

- However, the formation of an equitable cradle-to-grave care economy in Malaysia is undermined by several factors, including: a heavy reliance on informal care with limited support for caregivers; an absence of social care from the country’s social protection framework; a lack of social care services that meet preferences; inadequate legislation governing the care economy and workforce; and the general perception that care is predominantly a “women’s issue”.

- To build an inclusive and equitable cradle-to-grave care economy, Malaysia will need to realise a far more inclusive approach, by reframing and revaluing care as a public good, adopting a life cycle approach to care, while also ensuring that all income groups have access to a baseline of social care.

- At this juncture, public investment and involvement to set the foundations of a cradle- to-grave care economy are necessary. This would entail pursuing four important policy directions, such as integrating social care into the social protection framework, investing in community-based care infrastructure and services, establishing policy roadmaps and corresponding governance structures, and instituting system-wide gender-sensitive and care-centred approaches.

1. Introduction and the case for care as a driver of economic growth

Investing in Malaysia’s care economy is among the nation’s most crucial policy priorities in the coming decade. Malaysia is already undergoing rapid demographic change, with projections indicating it will become an aging nation by 2030 as fertility rates decline.4 This demographic shift is set to increase the old-age dependency ratio while reducing the proportion of the population that is of working age.5 Concurrently, evolving family structures and a decline in multi-generational households are leading to more people living apart from their families.6

These socioeconomic and demographic shifts highlight a surge in care needs – which are set to grow in the coming decade as Malaysia navigates the transition into high-income economy.7 However, the current care infrastructure, both formal and informal, is inadequate in terms of affordability, accessibility and quality to meet this growing demand for care – creating a growing “care gap” that has far-reaching implications for the socioeconomic fabric.

If this growing care gap grows unchecked, it will be families, particularly women, who will bear the brunt of its consequences.8 Without greater investment in the care economy, care responsibilities will continue to fall largely on families and informal caregivers. This situation will exacerbate the already high unpaid care and domestic work burdens for women in Malaysia.9

In the short term, this means women reallocating time from formal employment to caregiving, leading to reduced work participation and intensity.10 Over the long term, it risks hindering human capital accumulation and labour productivity growth, while setting back years of progress on improving women’s economic outcomes. As such, care is a strategic issue, central to the question of nation-building, economic development and social inclusion.

Indeed, most care work is currently provided informally by families, primarily women. In a week, women spend at least 10 more hours on care work than men.11 This care and domestic work is typically not remunerated, excluded from GDP calculations and does not come with the attendant social and labour protections afforded to a full-time worker in paid employment.

Using standard methods of approximating the market value of domestic work,12 our analysis indicates that if the unpaid care work produced in Malaysian homes every day were valued in national GDP figures, this would create about RM379 billion in economic value.13 In fact, unpaid care and domestic work would account for about a fifth of the service sector alongside market services (Figure 1). As a standalone services subsector, it would form the largest sector after manufacturing if valued in GDP (Figure 2).

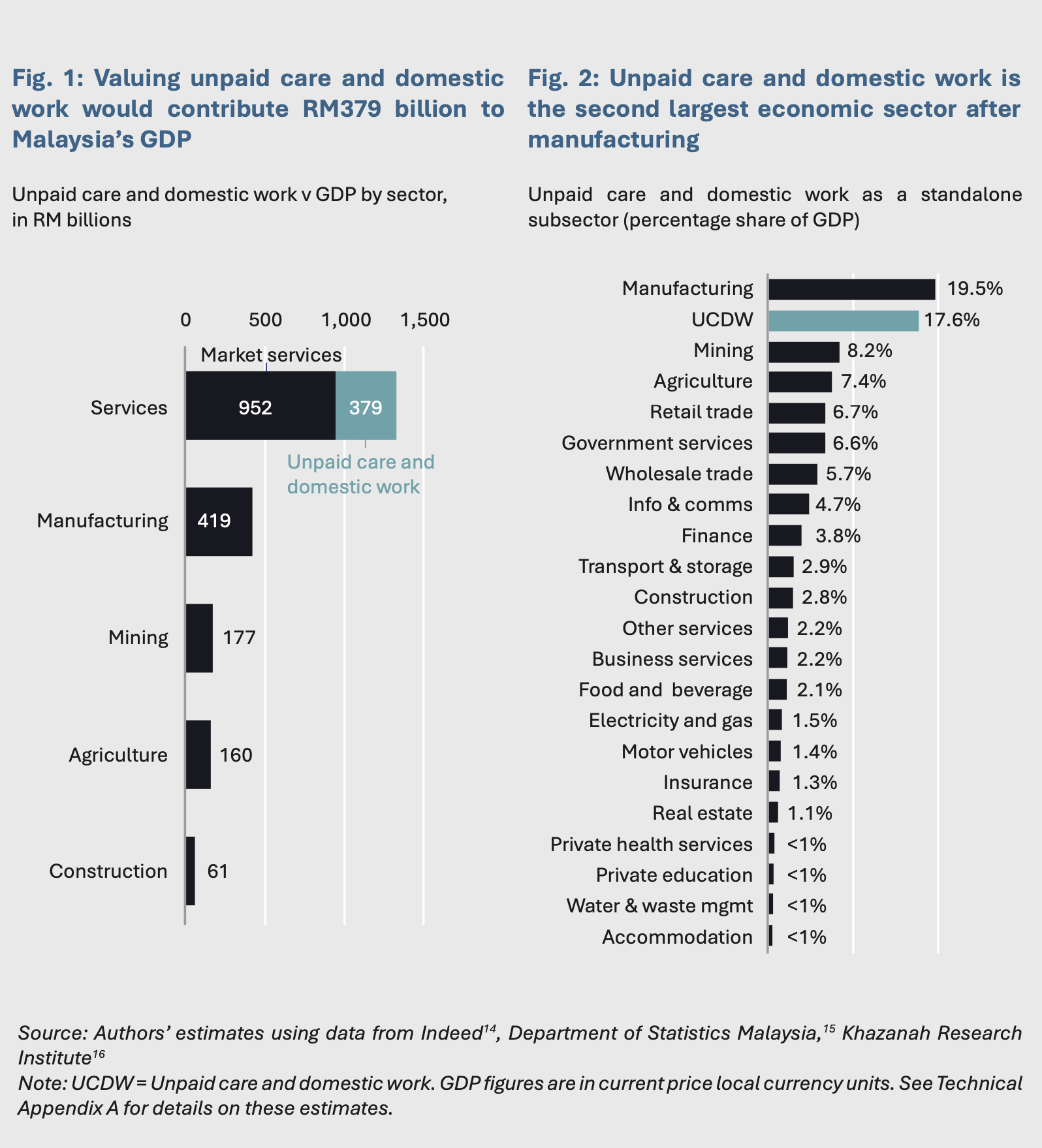

These figures underscore the potential gains from valuing care work, not least for Malaysians who want to work but are unable to because of family and care duties. In 2022, more than 3.1 million people remained outside the labour force due to family obligations and housework and a further 21,100 remained in part-time employment for the same reason.17 Together, this represents about 3.2 million Malaysians who were forced to reduce work hours or drop out of the labour force because of domestic work obligations, of whom 98% are women (Figure 3).

We estimate that the direct effect of potential market gains from fully enabling 3.2 million workers, both on the margins to participate in paid employment or go from part-time to full-time, is about RM77.2 billion in economic value per year.18 This adds about 4.9 percentage points in GDP terms for 2022 alone (Figure 4). Additionally, as most of these 3.2 million workers are women, this is projected to increase women’s labour force participation from 56% in 2022 to about 83% – effectively closing the gaps in workforce participation between women and men, and beyond Malaysia’s current target of 60%. These estimates represent the potential of removing the constraints to work because of care and domestic obligations, restoring freedom and choice for millions of workers to engage in market employment.

These estimates do not factor in short-term labour market frictions and/or changes to labour force structure, nor do they model the welfare impacts that could arise from shifting home production to market services. Additionally, it also focuses solely on direct impacts and excludes the knock-on benefits of stronger labour market attachment and potential human capital development.

Yet, these preliminary estimates paint a conclusive picture: in the absence of any policy change in public investment in care, Malaysia stands to lose out on significant gains in both economic growth and gender equality. Furthermore, Malaysia will continue to contend with a growing care gap, in turn perpetuating barriers to self-determination and limiting choices for millions of Malaysians who are forced to make their labour supply decisions based on their care responsibilities.

At this juncture, the imperative for greater public investment in Malaysia’s care economy has never been clearer, not least because care work, both paid and unpaid, enables all other forms of work in modern society.20 Care work creates benefits that accrue not just to the direct users of care, such as households, families and dependents, but also creates wide-ranging positive externalities that benefit the broader economy and society. Greater provision of care, thus, increases growth and productivity while promoting greater equity.21 Expanding public investment in closing care gaps would enable millions of Malaysians and their families to make the choice of shaping their desired socioeconomic outcomes. As such, Malaysia stands to benefit from building a cradle-to-grave care economy, recognising and responding to care needs across the spectrum, from child to elderly care.

2. Policy gaps

Care must be recognised as a strategic issue central not only to daily life but to social wellbeing and national development. To do so, various policy gaps must be addressed to ensure solutions respond directly to the realities faced by women and families. This section presents an assessment of existing policy gaps in the current approach to social care, especially as it relates to the two primary care needs – child and elderly care.

2.1 Heavy reliance on informal care arrangements

Care work is primarily undertaken informally in Malaysia, often going unpaid or underpaid, and is carried out primarily by women family members. This is true for both elderly and childcare.

When it comes to elderly care, the high costs of engaging formal care services coupled with normative views on filial piety leave families and communities almost entirely responsible for the care.22 Malaysia’s strategies for elderly care provision emphasise the role of familial care through encouraging adult children to care for elderly family members. Public investment in social care in Malaysia focuses primarily on direct service provision through institutional care, restricted to those who are poverty-stricken, alongside grants for civil society.23

Elderly care is, thus, propped up by informal caregivers, with some reliance on formal care for healthcare needs.24 Looking closer, most informal caregivers were women aged 36-59.25 This indicates that informal caregivers continue to provide care well into old age. Despite intergenerational support in Malaysia remaining strong,26 this model is increasingly being strained by urban migration, financial challenges and inadequate housing.27

As Malaysia ages, care needs will not only grow but also become more complex, because of the elderly requiring more specialised forms of care in line with their health status. The majority of elderly carers in the National Health and Morbidity Survey suffer from at least one illness and have little to no adequate training to cater to complex care needs.28

Similarly, for childcare, close to 99% of children aged three and under were cared for informally by family members, including grandparents, unregistered childcare centres, and/or other informal care arrangements in 2018.29 The percentage of children in the formal care sector remains relatively small, with 2019 data indicating that enrolment rates for children aged 0-3 and 4-6 years old in formal childcare centres and preschools falling short of government targets.30

This reliance on informal caregiving may prove unsustainable over the long run, with Malaysia’s care burden across the spectrum set to increase.31 This is especially the case as caregivers age while the number of family members that can be relied on for care decrease, and as urbanisation and housing circumstances erode multi-family living. If Malaysia is to continue relying on informal caregivers as the backbone of the care economy, this will require more targeted public support, especially because the costs of care are borne by informal caregivers through lost earnings, pensions and diminished career progression.32

2.2 Absence of social care from social protection framework

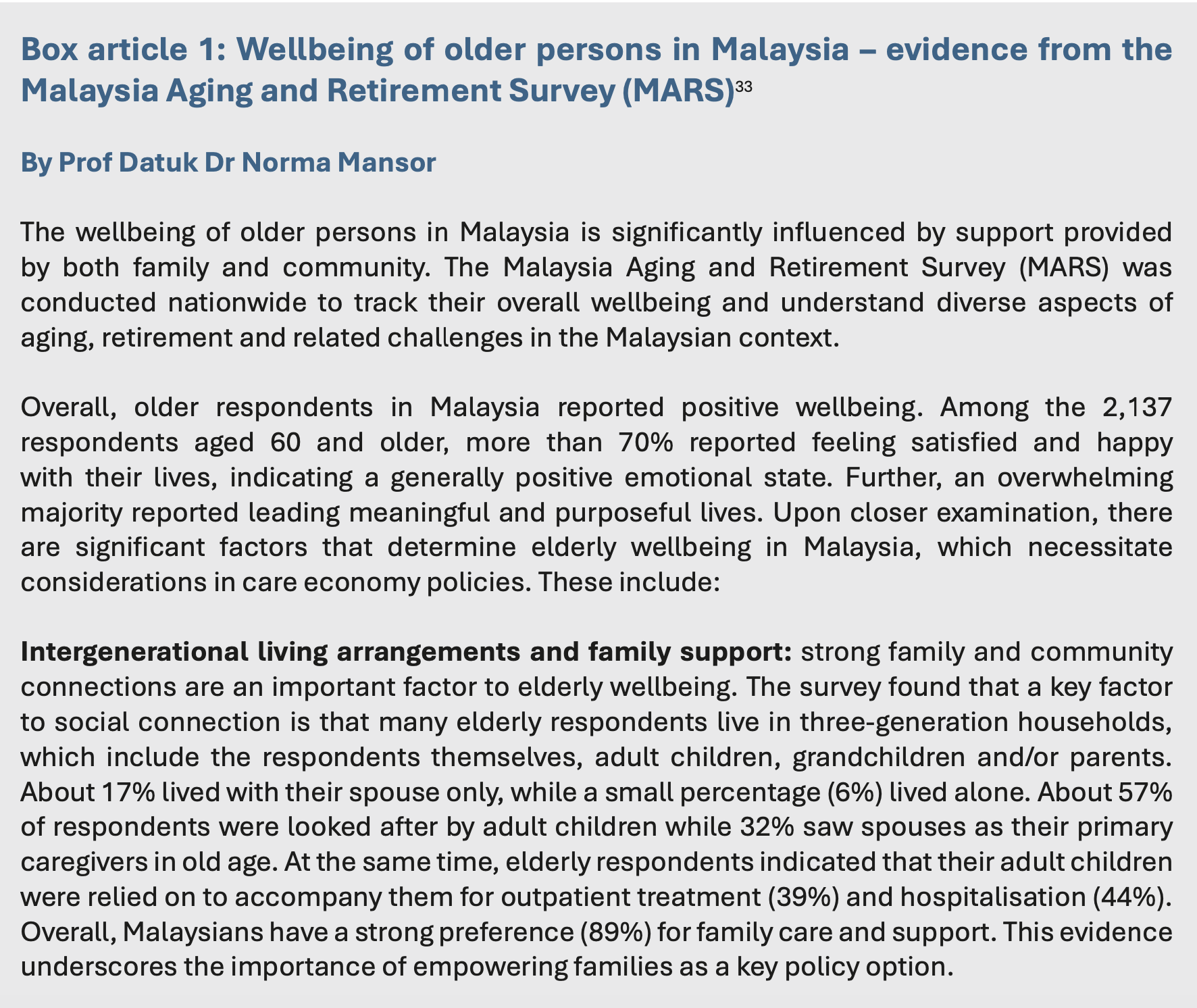

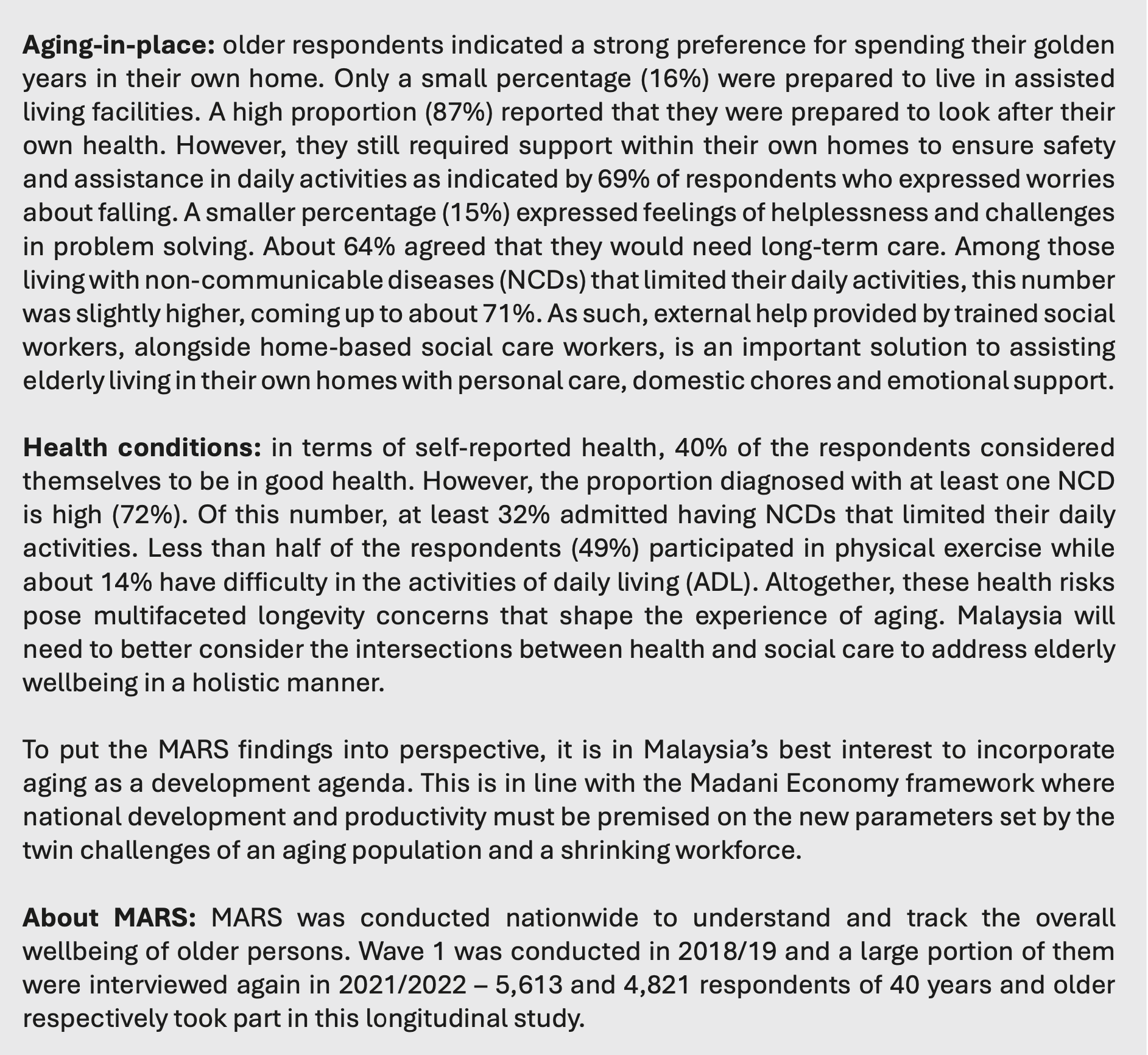

There exists a social care gap in Malaysia’s social protection framework. Currently, the framework can be organised into three pillars: (1) social safety nets aimed at poverty eradication; (2) social insurance for income replacement; and (3) labour market policies (Figure 5).34

Respectively, these serve protective, preventive and promotive functions. The current framework revolves around formal employment, with both transfer and social insurance mechanisms tailored around an income-tested, needs-based model that determines who does and does not receive support, including non-financial healthcare support for the elderly through the public health system.35 However, while the tax-funded healthcare system provides relatively affordable and efficient medical care for the elderly, it notably lacks coverage for social care.36 This absence of social care means that low-income women and families will often not have access to a baseline of care, as even public social care services are low in coverage.

Malaysia has since made headway in recognising unpaid care work by extending social safety nets to housewives through the i-Suri and i-Sayang under the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) and the Housewives’ Social Security Scheme under the Social Security Organisation (Socso). The i-Suri and i-Sayang initiatives offer housewives and women heads of household monetary incentives based on their contributions and allows husbands to transfer a portion of EPF contributions to their wife’s account respectively. Meanwhile, the Housewives’ Social Security Scheme insures housewives from injury or invalidity. However, these initiatives do not fully compensate informal caregivers for losses incurred from unemployment and reduced income – with the exception of the i-Sayang, which was recently expanded to include househusbands – targets only women, limiting the possibility of men taking on the role of informal caregivers.37

Moving forward, integrating social care as a fourth pillar in the social protection framework is important to meet the growing demand for care services in Malaysia equitably (Figure 5). In fact, factoring social care into social protection could serve all three functions of being protective, preventive and promotive. By bridging social protection with access to expanded social care services, it could ensure basic care needs are met and, if effective, could eventually promote the economic opportunities of informal caregivers by facilitating their entry or re-entry into the labour market.

2.3 Lack of diversity and depth of social care services to meet care preferences

There is a need for broader configurations of social care for children and the elderly in Malaysia that are in line with the care preferences and working arrangements of different families.

Malaysia’s elderly indicate a strong cultural preference for aging-in-place, in their own homes and communities. This is at odds with the public social care services that are available – currently, elderly public care services in Malaysia are focused on institutional care designed to serve only extremely vulnerable elderly individuals who lack family support or financial resources.40 There are also public support services and temporary respite care available for when family caregivers are unavailable41 but the number of beneficiaries of these programmes is small. Overall, public social care services are focused on providing care to the elderly, on an individual basis, and is less focused on addressing long-term caregiving systematically.42 As such, there is a mismatch between care preferences of the elderly and available public social care services.

Private care services offer a wider configuration of care services beyond institutional care that can certainly respond to this demand. However, given that elderly care is resource-intensive in nature, private social care services are accessible only to those who can afford them, making coverage both low and uneven.43 Establishing a wide range of care infrastructure that not only responds to care needs but is also affordable and accessible is of crucial importance.

Meanwhile, for childcare, there is also a mismatch between the demands of parents with available services. Only one in 10 registered childcare centres is listed as “workplace childcare centre”,44 despite parents continuously ranking workplace childcare centres as their most preferred childcare arrangement.45 The majority of workplace childcare centres are placed in public sector institutions and multinational corporations,46 which render them inaccessible to nearly half of all Malaysian workers.47 While the government has made many attempts to encourage the establishment of workplace childcare arrangements by providing incentives like tax reliefs, this has not led to a significant increase in the number of workplace childcare centres. Employers cite resources and cost as main barriers, making it a difficult commitment for SMEs.48

2.4 Gaps in legislation governing care and professionalisation of care workforce

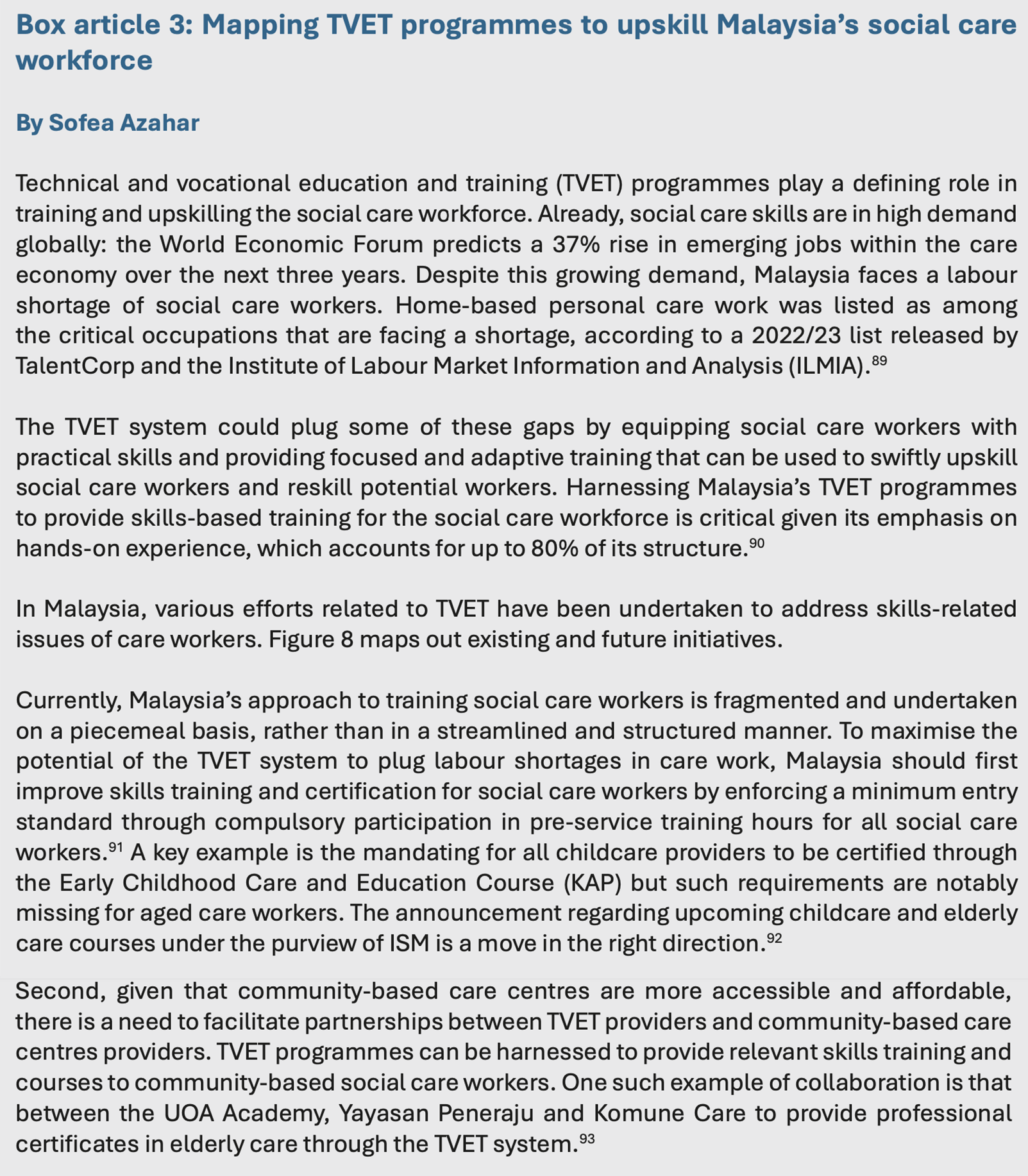

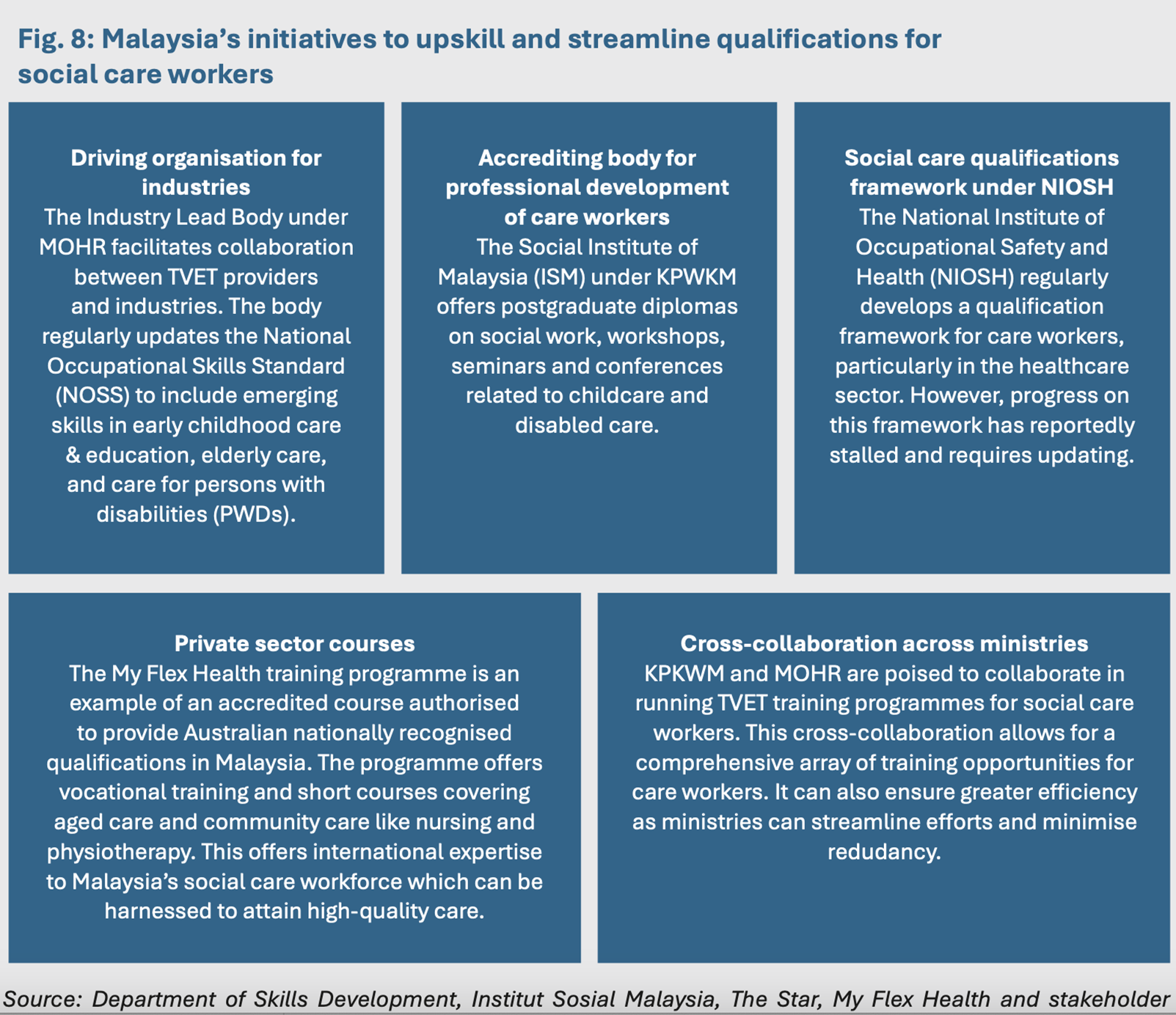

Malaysia lacks consolidated legislation and policy on the care economy as well as regulatory frameworks to sustain a highly qualified social care workforce in the long term. These gaps in legislation and policy need to be addressed to build the necessary foundations of a care economy and ensure a well-trained workforce to meet care needs.

For one, there are existing legislations relevant to the care economy – but they are distributed and fragmented across various acts and policies. The three most relevant legislations regulating the provision of care services are the Childcare Centre Act 1984, Care Centres Act 1993 and Private Aged Healthcare Facilities and Services 2018. These are regulatory frameworks that posit minimum standards of care covering issues, such as registration, licensing, control as well as inspection of care centres – which are essential in governing the quality of formal care centres.

Malaysia has also outlined policy roadmaps, specifically for the elderly through national-level blueprints like the National Policy for Older Persons 2011 under KPWKM and the National Health Policy for Older Persons 2008 under the Ministry of Health (KKM). These contain strategies towards addressing elderly wellbeing. The Senior Citizens Bill and the Social Work Profession Bill, which are currently being drafted, will also be relevant.

Meanwhile, when it comes to childcare, regulatory standards are primarily guided by international principles stemming from the Convention on the Rights of Child (CRC). Taken together, the existing legislations and policies in place lack a cradle-to-grave approach that recognises care needs across the life cycle. To formalise Malaysia’s commitment to building a cradle-to-grave care economy, the country needs streamlined legislations and strategies to address the care economy in the aggregate, outlining strategies for state involvement and investment, as well as regulatory frameworks that are applicable across public and private social care services.

Further, legislation or policies to professionalise social care work are inconsistent. Childcare policies that support care workers through building networks, facilitating skills training and peer support are also notably missing.49 This is particularly important because social care workers are generally seen as engaging in low-skilled work. They report being underpaid, overworked, with limited options for career progression50 – which undermine labour supply for the care workforce.

Professionalising social care work means regulating and registering social care workers, raising and streamlining formal qualifications, providing opportunities for training, and outlining the terms and conditions of social care work clearly under the Skills Development Department (JPK) in the Department of Social Welfare (JKM).51 This would go a long way towards valuing social care work and recognising it as a profession in its own right. In this regard, the Social Work Profession Bill, aimed at professionalising social work, is a good example of legislative action and a first step that should also be adopted for social care workers.52

2.5 Perception of social care as a predominantly ‘women’s issue’

While the government recognises social care as an issue of national interest, this has been typically approached from a narrowly defined gendered outlook, with KPWKM as the sole ministry to implement care-related policies.53 Here, care is tied up with pervasive gender and filial norms, resulting in relatively modest levels of public investment because social care is seen as first and foremost, the responsibility of the individual and family.54 However, approaching social care primarily as a women’s issue undermines the fact that to build a viable cradle-to-grave care economy that is a source of growth for Malaysia, it needs to be addressed from a multisectoral approach that spans various ministries.55

3. Establishing a vision of a cradle-to-grave care economy for Malaysia

At this juncture when Malaysia is designing policies to build its care economy, it is of critical importance that the country determines how comprehensive or expansive its care economy should be. This section maps out a vision for the care economy, by making aspirational comparisons with other countries, and highlighting key guiding principles for the formulation of an equitable cradle-to-grave care economy.

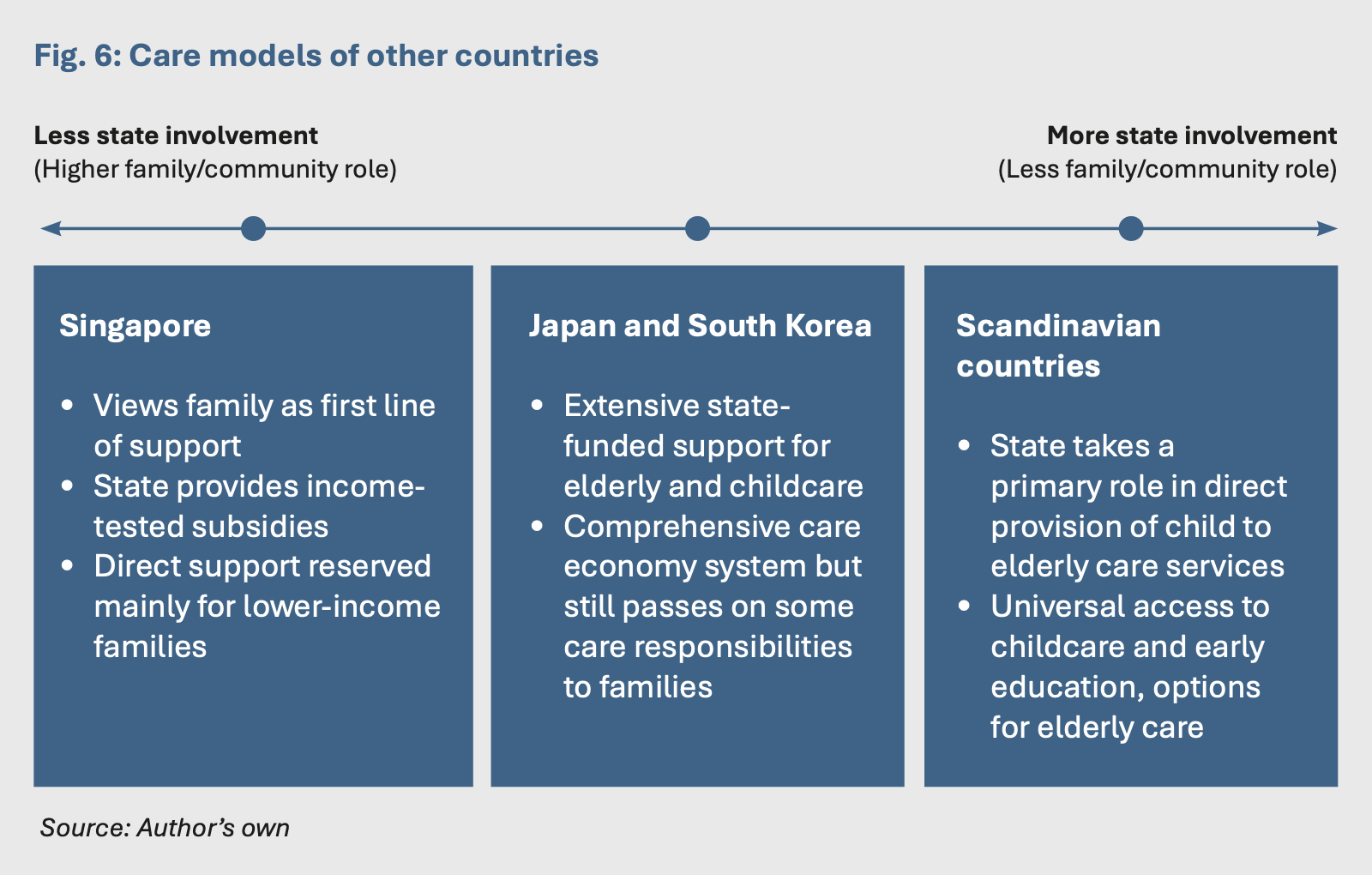

First off, benchmarking against countries that have similar cultural and societal norms is an important step as it allows us to take stock of the mix of policy tools available. Countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore have placed similar cultural emphasis on the role of families in providing care. Despite that, these countries have built robust care economies with various levels of state involvement.

Both Japan and South Korea’s approach combines several policy tools to ensure care: social protection schemes to support the elderly coupled with either public or subsidised services, while maintaining emphasis on family support and community involvement.56 Both have in place comprehensive social safety nets for the elderly and public care services,57 alongside a thriving private care industry.58 Meanwhile, Singapore continues to maintain family as the first line of support, especially for elderly care,59 where benefits are primarily targeted at low-income groups. These care models employ a range of policy tools like subsidies, direct provision of services and social protection through long-term care insurance (LTCI).

The Scandinavian care models are based on the principles of universalism. Here, social care services are widely available and accessible, designed to be gender-sensitive, are utilised by all socioeconomic classes and run by municipalities.60 This model represents the most comprehensive provision of a baseline of care.

As such, these care models serve as useful points of reference for Malaysia in designing the accessibility and equitability of its care economy. Figure 6 outlines where these three countries stand in terms of state involvement in social care vis-à-vis family/community with Scandinavian countries representing the highest level of state involvement as direct service providers, and Singapore at the other end with higher involvement by family and community. While these represent high-income countries whose care models remain largely aspirational for a middle-income country like Malaysia, policy lessons from these countries indicate the need for less developed countries to scale up such benefits over time, starting with less generous and means-tested benefit packages and expanding them as financing becomes more accessible.61

3.1 Approaching care as public good

As Malaysia ages, it is crucial that the approach to the care economy involves reframing social care as a public good to ensure affordability and accessibility by all income groups.

Malaysia’s care gaps are largely indicative of a longstanding public under-involvement and underinvestment in social care. These low levels of state involvement and investment in social care underline Malaysia’s approach to social welfare – with the government taking up what can largely be seen as a “residual role”.62 When compared to domains like healthcare and education, care-related social welfare services stand as one of the nation’s most inadequate support systems.63 Spending on health and education in Malaysia is already low for its level of development64 but it is still 1.5 times and twice higher than share of expenditure allocated for social care.

Social care has thus been relegated to three realms: privatised to the family through emphasis on informal caregiving, supported by the voluntary sector (i.e. civil society organisations), and increasingly, to the market. This low level of state involvement aligns with the government’s intended shift from playing a role as a “supplier and provider” to a “purchaser and regulator”.65

As a result, the care economy is developing more efficiently in the private sector, as evidenced by the general range of services available. However, while the private social care sector is a crucial pillar of the care economy, this alone will be insufficient to meet Malaysia’s growing care needs – nor is it widely accessible to low-income and vulnerable groups.66 The nature of care as an inherent public good means that market forces tend to underinvest and underprovide care in equilibrium. A total reliance on the monetisation of social care is far from a comprehensive or equitable solution towards addressing care gaps.

To approach care as a public good, stronger public involvement and investment is crucial. This also does not imply that the private sector would be crowded out – but rather that public investment could present opportunities as it could set the foundations for greater private investment while growing different target markets for private care services.

3.2 Applying a life cycle approach to care economy

A life cycle approach recognises the various risks and vulnerabilities that individuals face throughout their life span.67 Applying the life cycle approach to care allows for the consideration of diverse social care needs as existing on a spectrum, spanning child to elderly care – and not excluding specialised care like disabled or palliative care required throughout or during specific periods of a person’s lifetime. This is what is meant by building a cradle-to-grave care economy.

The life cycle approach facilitates a more inclusive conception of social care needs. Child and elderly care are often considered separately in policy and practice because of the marked differences in needs: childcare requires an educational component, while elderly care brings with it healthcare requirements. Further, disabled care needs are commonly seen as separate from the mainstream spectrum of care, given the specialised skills it requires.

However, integrating all care needs under the umbrella of the care economy allows for a holistic approach responsive to dependents’ needs across their lifetime. For example, children require care well into adolescence, beyond the age groups of 0-3 (care centres) and 4-6 years (preschool), as outlined in Malaysia’s early childcare and education model. When it comes to the elderly, they will often require care on a day-to-day basis, beyond the point of illness or hospitalisation. Disabled care needs intersect across childhood and adulthood, with risks increasing with old age. As such, a life cycle approach recognises these needs and aims to offer a spectrum of services or support.

3.3 Offering all Malaysians accessible baseline of care

To ensure the care economy is equitable across all groups, there needs to be an accessible minimum baseline of care. However, the primary targets should be low-income groups who often face several unmet social needs simultaneously.68 What this ensures is that even in times of crisis, social care needs are still met, without which would expose vulnerable families to further risk. In practice, this should represent a social protection floor that enables all families to access social care when they require it.

4. Policy recommendations

The vision of an equitable cradle-to-grave care economy requires setting important policy reforms – spanning social protection, legislation and governance, and gender-sensitive policymaking. To that end, Malaysia’s approach to the care economy should follow four policy directions:

1. Integrating social care into the social protection framework

2. Investing in community-based care infrastructure and services

3. Establishing policy and governance for social care

4. Instituting system-wide gender-sensitive and care-centred approaches

POLICY DIRECTION 1: Integrating social care into Malaysia’s social protection

framework

4.1 Establishing primary caregiver support through social protection

Given that care is largely performed informally, an important public investment in social care involves providing protection for primary caregivers, especially those with long-term care responsibilities. Informal caregivers can be supported through a range of social assistance measures, including cash transfers, cash-for-care benefits, family allowance or pension credits targeted specifically at informal caregivers. This is crucial as most caregivers are unpaid and accrue health and socioeconomic costs, while potentially having more than one dependent to care for or other mitigating circumstances like disability or being the sole caregiver. Using transfers to offset the loss of income from engaging in caregiving activities instead of paid work will prevent further deprivation of low-income caregivers and tangibly recognise the value of care in society as a productive activity.69 Refocusing policy on caregivers instead of only care recipients represents a person-centred approach that recognises the costs of caregiving and seeks to redress it.

A policy example of compensating caregivers includes Singapore’s monthly Home Caregiving Grant (HCG), which ensures financial support for households with the elderly, especially those with moderate to severe disabilities.70 Singapore’s care model provides direct support for low-income families, be it social care services or financial assistance, while encouraging voluntary contributions through the Central Provident Fund (CPF). Singapore also allocated in 2019 a top-up through the CPF to enhance the retirement savings of low-income individuals.71 Altogether, the HCG and CPF top-up initiatives are important measures that could also be considered by Malaysia’s Employees Provident Fund (EPF).

More broadly, supporting Malaysia’s primary caregivers through social protection could encompass a two-pronged strategy, including:

- Instituting caregivers’ allowance: this allowance could be means-tested and provided depending on the intensity of care needs (i.e. disability), serving to compensate partially or fully informal caregivers who provide full-time care. In practice, this could be similar to cash-for-care benefits, helping to improve the welfare of caregivers while reducing the disparities between those performing paid and unpaid work. It could also enable them to afford care, allowing them to seek paid employment.

- Enhancing retirement savings: extend EPF coverage for those who are full-time caregivers, or who are forced to leave work for caregiving responsibilities. Similar to programmes like i-Saraan, the government could incentivise voluntary contributions by offering matching contributions or top-ups to caregivers’ EPF.72

4.2 Bridge social protection with access to social services

In the long run, social protection measures like cash transfers and social insurance cannot replace affordable, accessible and quality social care services, especially when it comes to elderly care.73 The healthcare system, as it stands, is also neither adequate nor suitable to cater to everyday social care needs.74 In this regard, the government plays a crucial role in financing, regulating and, to an extent, providing social care services for low-income groups to prevent the reproduction of further inequalities. On this, Malaysia’s social protection framework must be expanded by bridging it with access to social services. This could form a social protection floor or baseline of care for all Malaysians.

A viable mechanism that can help achieve this is long-term care insurance (LTCI) – a key health agenda that countries with aging populations have established. Taking the example of Japan and South Korea, their LTCI programmes bridge the link between social transfers and social services by allowing access to different types of care, such as home, visiting, institutional and community care, with eligibility for all citizens over 65.75 These LTCI programmes are cross-subsidised, funded by taxes, social insurance and co-payments – with subsidies for low-income groups.76

For Malaysia, early financing is necessary because it allows the service-delivery system a buffer period to adapt and build up before demand for resources grows, especially as the current care infrastructure is lacking.77 While Japan’s and South Korea’s care models are largely aspirational, policy lessons from these countries indicate that it would be better to start with less-generous benefits and restricted schemes before scaling up over time.78 This may be useful for the case of childcare as well, taking on a tripartite funding model that spreads the cost across employers, parents and government.

POLICY DIRECTION 2: Investing in community-based care infrastructure and

services

4.3 Diversifying social care support services to be more flexible and respond to different needs

For Malaysia’s care economy to respond effectively to social care needs, it will require a wider and more accessible range and depth of services than are currently available. The care economy should essentially allow recipients to choose the type of care they want to receive. To fill this gap, community-based and home-based models are an important care configuration as they provide care and support within the communities that they live and interact in – places that “people call home” – which could serve to be more affordable and accessible in the long run.79

For the elderly, community-based and home-based care promotes aging-in-place and independence in ways that institutional care lacks. Diversifying how these social care services are provided is key, hence services should include arrangements like adult daycare, home visits, community activities and programmes, and respite care. This is important as primary caregivers can only work and flourish if they have access to adequate formal care support that are flexible and tailored to their needs.

Malaysia already has a community-and home-based care model in place for persons with disabilities (PWDs) under the purview of the Disabled Development Department (JPPWD) placed in JKM.80 The next step would be to expand this existing model to the elderly while facilitating uptake and support within vulnerable communities.

At the same time, Malaysia will have to consider integrating its social and health care systems. The latest Health White Paper offers key opportunities for such a move as it outlines a transition towards “person-centred care and bringing care nearer to the community” and moving services like transitional care out of the hospital to the community level.81 This offers the opportunity to move beyond medically-oriented care to include social care services required beyond the point of illness.

Community-based care may also be feasible and attractive options for working parents in the absence of workplace childcare. These can connect and integrate parents to a wider network of relatives, friends and neighbours. At the same time, employers also play an important role in recognising and supporting the care responsibilities of their employees. Companies within a common area should be incentivised to pool resources and funding to set up childcare centres as another mode of community-based care. Providing corporate guidance, training and skills to empower companies to do this will be key. Childcare centres also need to have extended hours to cover the full workday and be flexible enough to accommodate irregular work shifts.

Community and home-based social care centres will ultimately require more collaboration across all government levels, from federal to state to local government. Implementation, monitoring and regulation must be decentralised to the district level. Improving implementation and governance structures should go hand in hand with diversifying the services provided in the care economy in ways that are flexible and convenient to the communities it aims to serve.

POLICY DIRECTION 3: Establishing policy and governance for social care

4.4 Outlining legislation, policies and roadmaps for the care economy

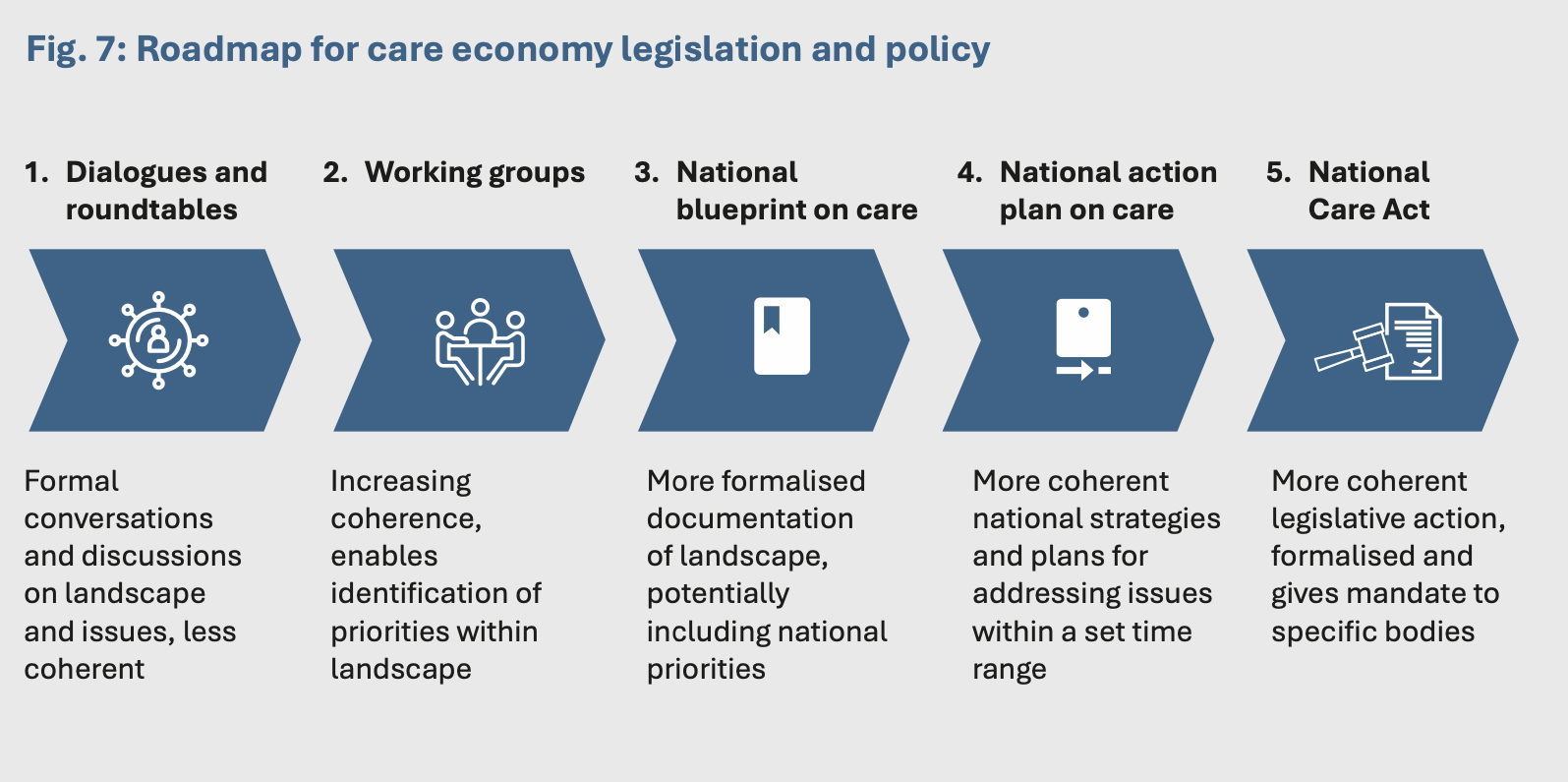

While the concept of a care economy is featured in the Madani Economy framework, Malaysia has yet to outline tangible steps towards developing it. Legislation, policies and governance frameworks that outline a more systemic approach to the care economy are necessary. Figure 7 identifies a five-point road map to set the legislative and policy foundations for a cradle-to-grave care economy.

Based on Figure 7, the preliminary steps would be to strengthen institutional coordination and collaboration through multi-stakeholder dialogues, roundtables and working groups. In other countries, formalising structures for collaboration and engagement across stakeholders has led towards the identification of priorities and ultimately, more concrete outcomes, such as those illustrated from steps 3 through 5. For example, in Argentina, the creation of an inter-ministerial commission on care in 2020 brought together 12 agencies to plan and formulate social care policies.82 Similarly, in Nepal, an inter-ministerial National Steering Committee on Decent Employment and Care Economy (NSC), situated under the National Planning Commission, was established to develop policies and grow investments in the care economy.83

Malaysia’s care economy would benefit from developing a national care blueprint and a formal policy document, such as those outlined in steps 3 through 5. These, however, are incremental changes that are built over time, demonstrating a strengthening commitment to developing the care economy.

A blueprint, as outlined in step 3, offers the simplest way of formalising this commitment. While the Ministry of Economy is currently working on a National Aging Blueprint,84 Malaysia’s care economy landscape would benefit from a blueprint for the overall care economy that encompasses aspects of both paid and unpaid care from a life cycle perspective. With a national care blueprint, a better understanding of the current landscape and existing gaps could be mapped out while also prescribing the overarching perspectives of how the care economy should be shaped.

Step 4, a national action plan (NAP), would build off this foundation. A NAP for care would articulate strategies to approach the care economy. A NAP would be more concrete than a blueprint and is often used to articulate priorities and actions that countries have committed to.85 An example from Indonesia is relevant here: the country’s Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Children Protection (KPPA) is currently leading the development of a National Action Plan on the Care Economy, which will be included in its Long-Term National Development Plan 2025- 2045.86 Malaysia could benefit from this type of policy document in the medium term and it would go a long way towards formally recognising social care as a strategic issue, and integrating it into wider development plans.

Finally, step 5 is a National Care Act, the most coherent legislative action where a mandate can be assigned to a particular ministry or group of ministries, with clearly outlined definitions, minimum standards, and regulatory and monitoring responsibilities. A key example is Uruguay’s Care Act, adopted in 2015 to avert what was feared to be a care crisis.87 Under the act, all children, persons with disabilities and elderly persons were given the right to access care.88 Ideally, this is what Malaysia should aspire to.

4.5 Recognise, professionalise and regulate the social care workforce

Concurrent to a national strategy, legislative action will also need to address the professionalisation of social care workers to sustain and streamline the quality of care. There is already legislation in motion that could serve as an example: the Social Work Profession Bill aimed at professionalising social work in Malaysia, which has yet to be tabled in Parliament. However, even if passed, the bill is likely to benefit only social workers and it will not impact all forms of social care workers across the public and private sector.

As such, social care workers will require separate legislation aimed at professionalising the workforce. Professionalisation of social care workers needs to be formalised in national policy documents – such as through blueprints, plans and acts related to care. This is crucial to systematically enable the growth of the formal care sector – which would be hampered if it is otherwise unable to attract and build a qualified workforce in sufficient numbers. Once the Social Work Profession Bill is passed, this should pave the way for a similar act targeted at social care workers to raise formal and paid care work to a professional level.

At the baseline, legislations to professionalise social care work must include the following components, including: (1) standardising and improving education and training to grow the skills needed for a qualified care workforce, (2) outlining the terms and conditions of social care work, (3) professionalising care workers in line with the status of professional workers i.e. healthcare workers (for elderly or disabled carers) and/or school teachers (for childcare workers), (4) offering employment protections to social care workers through social protection, and (5), instituting regular monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for quality.

4.6 Instituting a multisectoral approach to the care economy

Currently, progress on the care economy is spearheaded by KPWKM, given that care is seen primarily as a women’s and welfare issue. However, the task of building a robust cradle-to-grave care economy is best-served by multisectoral collaboration, with involvement of various ministries, agencies and levels of government. This is critical as coordination across sectors could remove barriers to implementation, promote scale-up and maximise the impact that a single entity would not have the capacity to perform.94

As such, the care economy needs to be the shared responsibility of multiple other ministries, as key stakeholders whose active participation and response are integral. This includes: the Ministry of Economy to recognise and value the contribution of care to national GDP and facilitate the growth of an industry of social care services; Ministry of Human Resources to oversee the skills training and employment conditions of social care workers; Ministry of Health to better integrate the health and social care towards playing a preventative health role; and Ministry of Education where early childcare and education is concerned.

To this end, an inter-ministerial committee is needed to coordinate cross-cutting responsibilities and streamline action towards the common goal of building a cradle-to-grave care economy that responds to Malaysians’ social care needs.

POLICY DIRECTION 3: Instituting system-wide gender-sensitive and care-

centred approaches

4.7 Collect, publish and integrate data on unpaid care work and the care economy

Building the foundations of a care economy requires recognising care work more formally and “making visible” what is normally conducted in the private realm of the home. To do this, data and statistics on unpaid home production and care work must be collected and made publicly available. Not only will this outline the urgent need for policy attention, but it will also be useful to drive evidence-based policymaking – an important task needed to justify significant public investments in the care economy. In this regard, Malaysia stands to benefit from taking on a nationwide time-use survey (TUS) to measure unpaid care work.95 However, a TUS may be costly and resource-intensive. As such, it may be more feasible for Malaysia to start by harnessing the household and labour force survey under the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) to collect data on unpaid care work and make this publicly accessible,96 although this would not be a perfect substitute for a TUS.

4.8 Mainstreaming gender-sensitive policymaking

Malaysia’s policies related to social care will need to be more gender-sensitive. At the baseline, being gender-sensitive in the context of care means recognising and responding to the underlying reality that men and women experience the need for care and its attendant policies differently. For example, women tend to live on average 4.5 years longer than men.97 They are also far more likely to be responsible for providing care for other family members well into old age98 and tend to have less savings. Their care needs and ability to access care differ from men’s and, as such, long-term care policies need to respond to these differences.

Additionally, it is often women who are overrepresented in the social care workforce – not only do they work in a context where care is undervalued, they are also concentrated in lower status, poorly paid or unpaid roles, which increase their socioeconomic vulnerability.99 As such, policies must recognise the inherently gendered elements of social care work and create conditions that value care. This approach should also be intersectional to respond effectively to diverse situations.

Gender-sensitivity needs to be complemented by a recognition that these experiences are further shaped by concrete circumstances like socioeconomic status, disability, migrant status, or race, for example. To make policymaking more gender-sensitive, intersectional considerations need to be systematically mainstreamed across all levels of government and in policy design.

Malaysia has made headway on this front, by disseminating the responsibility for gender equality across ministries through the establishment of gender focal teams (GFTs). Moving forward, building on the GFTs to mainstream gender and care considerations will be a key first step. However, establishing key priorities and success indicators for GFTs centred on care is key, while also training GFT experts and reporting on this progress across ministries – without which it would be difficult to measure effectiveness. Once these are in place, KPWKM should consider instituting mechanisms for accountability to ensure gender-sensitive goals are met.

5. Conclusion

The care economy is, at its core, an issue strategic to Malaysia’s development, not only because it stands to drive economic growth but also because it is critical to both the wellbeing and welfare of everyday Malaysians. It would play a key role in improving gender equality outcomes by providing concrete support to families and enable women to pursue economic opportunities. In total, Malaysia stands to benefit by investing in the care economy.

But the challenge lies in building a cradle-to-grave care economy that responds to the care needs of all groups amid rapid demographic change – while also ensuring that it is equitable and widely accessible. As such, it is of crucial importance that Malaysia shapes a vision of the care economy that is inclusive and comprehensive by reframing care as a public good, adopting a life cycle approach to social care and ensuring all Malaysians can access a minimum baseline of care.

Unlike most policy areas, social care is a domain that is particularly complex because it is closely associated with gendered and cultural norms. As of yet, Malaysia also does not have the foundations to ensure a thriving care economy, let alone one that spans from cradle-to-grave. This is where the country will have to pursue wide-ranging policy reforms, covering social protection, legislation and governance, community-based care infrastructure and services, as well as centring a gender-sensitive approach to policymaking. In all, these would be important policy directions, promising gains that would impact not only the care economy but the nation as a whole.

Endnotes

- OECD (n.d.). Quick guide to what and how – Entry points to recognise, reduce and redistribute.

- Contact. (n.d.). What is social care?

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Being a caregiver.

- National Population and Family Development Board Malaysia. (2017). Ageing phenomenon in Malaysia towards 2030.

- Hamdan et al, 2018. Aging workforce: A challenge for Malaysia. Journal of Administrative Science.

- National Population and Family Development Board Malaysia. (n.d.). Understanding Malaysian Families of Today.

- The World Bank. (2020). A silver lining: Productive and inclusive aging for Malaysia.

- Khalid, Haniza. (2023). Investing in the care economy: Opportunities for Malaysia. United Nations Development Programme.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- United Nations Women. (2018). Facts and figures: Economic empowerment.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- Argentina Ministry of Economy. (2021). The Value of Care: A Strategic Economic Sector A Measurement of Unpaid Care and Domestic Work in the Argentine GDP.

- See Technical Appendix A for more details and estimates.

- Indeed. (2023). Housekeeper Salaries in Malaysia.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2023). Quarterly national account – gross domestic product, fourth quarter 2022.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2023). Labour force survey report 2022; Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2023). Salaries and Wages Survey Report 2022.

- See Technical Appendix B for further details.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2023). Labour force survey report 2022; Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2023). Salaries and Wages Survey Report 2022.

- Argentina Ministry of Economy. (2021). The value of care: A strategic economic sector.

- Ramos, M. B., and Oguzhan, C. L. (2022). Female labour force participation and the care economy in Asia and the Pacific. UNESCAP Policy Brief.

- Abdul Ghani, N. et al. (2022). Knowledge, practice and needs of family caregiver in the care of older people: A review. International Journal of Care Scholars, 5(3), 70-78.

- Anuar, N.H. et al. (2019). Informal Caregiving of senior parents in Malaysia: Issues and counselling needs. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 5(6), 408-420.

- Z., Goh. et al. (2013). The formal and informal long-term caregiving for the elderly: The Malaysian experience. Asian Social Science, 9(4), 174-184.

- Kong, Y. et al. (2021). Factors associated with informal caregiving and its effects on health, work, and social activities of adult informal caregivers in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019. BMC Public Health, 21(1033).

- Malaysia Population Research Hub. (n.d.). Future Families of Malaysia.

- Alavi, K. (2014). Intergenerational relationships between aging parents and their adult children in Malaysia. In Torres, A.T. and Samson, L.L (Eds.), Aging in Asia-Pacific: Balancing the state and the family. Philippine Social Science Council.

- Kong, Y. et al. (2021). Factors associated with informal caregiving and its effects on health, work, and social activities of adult informal caregivers in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019. BMC Public Health, 21(1033).

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- Dhamotharan, M., and Foong, L. Towards the development of a Malaysian quality early childhood care and education: Policies, legislation and regulation. Millennia Comms.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- UNECE. (2019). The challenging role of informal carers. Policy brief.

- Malaysia Ageing and Retirement Survey Wave 2 (2021–2022): Survey Report. (2023).

- Rabi, A. et al. (2019). Longevity risk and social old-age protection in Malaysia: Situation analysis and options for reform. Social Wellbeing Research Centre.

- KWSP. (2016). Social Protection Insight.

- Yunus, R.M. et al. (2023). In search for a sustainable and equitable long-term care for Malaysia. Journal of Aging Social Policy, 35(6), 743-755.

- Lee, M.H. (2023). Caring for an aging Malaysia beyond gender and filial norms. ISIS Malaysia.

- Mansor, N. & Rabi, A. (2023). National Social Wellbeig Blueprint. Social Wellbeing Research Centre.

- Bank Negara Malaysia. (2020). Economic and Monetary Review.

- The World Bank. (2020). A silver lining: Productive and inclusive aging for Malaysia.

- Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat. (n.d.). Warga Emas.

- Hamdy, M.S. and Yusuf, M.M. (2018). Review on public long-term care services for older people in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Science, Health and Technology, 2, 35-39.

- The World Bank. (2020). A silver lining: Productive and inclusive aging for Malaysia.

- Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat. (n.d.). Senarai taska berdaftar.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat. (n.d.). Senarai taska berdaftar.

- Yap, B. How private and SME businesses can thrive under the Malaysia MADANI roadmap.

- Bunyan, J. (2018). Why aren’t childcare centres common in the workplace? Bosses explain. The Malay Mail.

- Ahmed, Tanima; Devercelli, Amanda; Glinskaya, Elena; Nasir, Rudaba; Rawlings, Laura B. (2023). Addressing care to accelerate equality. World Bank Group Gender Thematic Policy Notes Series. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Aziz, NAA. et al. (2021). Issues in operating childcare centers in Malaysia. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(3), 993-1000.

- Hayes, L. et al. (2019). Professionalisation at work in adult social care. Report to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Adult Social Care. Project report. GMB trade union.

- Note: It is important to note that while social workers include social care workers, not all care workers are considered social workers. As such, the Social Work Profession Bill will benefit only social workers, and not all social care workers.

- UNDP. (2015). Study to support the development of national policies and programmes to increase and retain participation of women in the labour force: Key findings and recommendations.

- Doling, J. and Omar, R. (2002). The welfare state system in Malaysia. Journal of Societal and Social Policy, 1(1), 33-47

- UNDP. Study to support the development of national policies and programmes to increase and retain participation of women in the labour force: Key findings and recommendations.

- Peng, I. (2017). Social policies and the care economy in Japan and South Korea: Taking stock of the opportunities and challenges for women’s economic empowerment. Commission on the Status of Women Sixty-first Session.

- Ibid.

- Rhee, J.C. et al. (2015). Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: Comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy, 119, 1319-1329.

- Gubhaju, B. and Chan, A. (2016). Helping across generations: Families in Singapore. CARE research brief.

- Antonnen, A. (2005). Empowering social policy: The role of social care services in modern welfare states. In Kangas, O. and Palme, J. (Eds.). Social Policy and Economic Development in the Nordic Countries. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Rhee, J.C. et al. (2015). Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: Comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy. 1319-1329.

- Ashray, F. (2018). Social welfare services in Malaysia: The role of government. Asian Association for Public Administration Annual Conference.

- Ibid.

- World Bank. (2020). Malaysia Human Capital Index 2020.

- The World Bank. (2020). A silver lining: Productive and inclusive aging for Malaysia.

- Antonnen, A. (2005). Empowering social policy: The role of social care services in modern welfare states. In Kangas, O. and Palme, J. (Eds.). Social Policy and Economic Development in the Nordic Countries. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Social protection. (n.d.). What is social protection?

- Kreuter, M.W. et al. (2021). How do social needs cluster among low-income individuals? Population Health Management, 24(3).

- Keefe, J. et al. Financial payments for family carers: Policy approaches and debates. In Martin-Matthews, A. & Philips , J.(EDs.), Ageing at the intersection of work and home life: Blurring the boundaries (pp. 185-206). New York: Lawrence Eribaum.

- Hingorani, S. (2019). Commentary: Caregivers are getting some support but deserve more care. Channel News Asia.

- Hingorani, S. (2019). Commentary: Caregivers are getting some support but deserve more care. Channel News Asia.

- KWSP. (n.d.). Retirement savings for self‑employed members.

- UNRISD. (2010). Why care matters for social development.

- Yunus, R.M. et al. (2023). In search for a sustainable and equitable long-term care for Malaysia. Journal of Aging Social Policy, 35(6), 743-755.

- Li, S. and Shi, X. (2021). A comparative study of long-term care insurance systems in Japan and Korea. Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Mental Health and Humanities Education (ICMHHE 2021).

- Yunus, R.M. et al. (2023). In search for a sustainable and equitable long-term care for Malaysia. Journal of Aging Social Policy, 35(6), 743-755.

- Rhee, J.C. et al. (2015). Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: Comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy. 1319-1329.

- Rhee, J.C. et al. (2015). Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: Comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy. 1319-1329.

- Thomas, C. (2021). Community-first social care: Care in places people call home. IPPR.

- Program Pemulihan Dalam Komuniti. 2017. Community-based rehabilitation program (CBR).

- Ministry of Health, Malaysia. (2023). Health White Paper for Malaysia.

- Ministry of Economy Argentina. (2021). The value of care: A strategic economic sector.

- The Asia Foundation. (2022). Toward a Resilient Care Ecosystem in Asia and the Pacific Toward a Resilient Care Ecosystem in Asia and the Pacific Promising Practices, Lessons Learned, and Pathways for Action on Decent Care Work.

- Ainin Wan Salleh. (2023). “Govt coming up with national ageing blueprint, says deputy minister”, Free Malaysia Today.

- The Danish Institute for Human Rights & International Corporate Accountability Roundtable. (2017). National Action Plans on Business and Human Rights.

- International Labour Organization. (2023, Argentine September 22). Indonesia identifies seven strategic issues for its Road Map and Action Plan on Care Economy [Press release].

- International Labour Organization. (2018, August 27). How a new law in Uruguay boosted care services while breaking gender stereotypes. [Feature].

- UN Women. (2017, February 28). In Uruguay, care law catalyses change, ushering services and breaking stereotypes.

- MOHE & Talentcorp. (2023). Critical Occupations List (MyCOL) 2022/2023: Sectors deep dive for the Malaysia National Skills Registry (MyNSR).

- Azahar, S. (2022). Policy Brief: Strengthening TVET capabilities in Malaysia.

- Hemmings, N., Oung, C. & Schlepper, L. (2022). New Horizons: What can England learn from the professionalization of workers in other countries?.

- Hairom, N. (2023). Kursus penjagaan kanak-kanak, orang tua bermula awal tahun depan. Sinar Harian.

- Lee, Y.X. (2023). UOA Academy, Yayasan Peneraju and Komune Care collaborate to offer professional certificate in elderly care through TVET. [online] UOA Academy.

- Simasiku, T. (2022). Multisectoral approaches to nurturing care programmes: A case study of opportunities and challenges in Zambia. Early Childhood Development Network.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to care: Gender inequality, unpaid care work and time use survey.

- UN ESCAP. (2022). How to invest in the care economy: A primer.

- New Straits Times. (2022, September 28). Malaysia’s average life expectancy declines.

- Kong, Y. et al. (2021). Factors associated with informal caregiving and its effects on health, work, and social activities of adult informal caregivers in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019. BMC Public Health, 21(1033).

- WHO. (n.d.). Value gender and equity in the global health workforce.

- Argentina Ministry of Economy. (2021). The Value of Care: A Strategic Economic Sector A Measurement of Unpaid Care and Domestic Work in the Argentine GDP.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2022). Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2022.

- Indeed. (2023). Housekeeper Salaries in Malaysia.

- SalaryExpert. (2023). Domestic Maid Salary in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.