Economics, Trade, and Regional Integration: Calvin Cheng, Hanson Chong, Jaideep Singh and Qarrem Kassim

Climate, Environment and Energy: Ahmad Afandi, Dhana Raj Markandu, Kieran Li Nair and Zayana Zaikariah

October 2024

Snapshot

The key initiatives announced as part of Budget 2025 across critical economic, social and environmental policy areas are listed below. More in-depth analysis of each initiative is provided in subsequent sections, accessible through the corresponding hyperlinks.

Fiscal policy and taxes

- Fiscal consolidation: Budget 2025 continues “soft-fiscal tightening”, prioritising revenue growth to reduce the deficit, aiming for a 3.8% deficit-to-GDP in 2025.

- Tax measures: expansion of the sales and service tax (SST) to luxury goods and services. Introduction of a 2% dividend tax on income above RM100,000.

- Development expenditure: shrinking as a share of GDP over the past two years, with concerns over the sustainability of development investments.

Subsidies and social protection

- Targeted subsidies: removal of RON95 petrol subsidies for the top 15% income group.

- Cash transfers: expansion of cash-assistance programmes (e.g., Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah), with a focus on the Sumbangan Asas Rahmah top-up programme.

- Social protection: incremental improvements to pension and social insurance coverage, but gaps remain for informal workers.

Industrial development and competitiveness

- New Investment Incentive Framework: targeted, performance-oriented incentives to promote high-impact investments.

- Electronics and semiconductors: new investments in hard and soft infrastructure for the electrical and electronics sector, including RM1.2 billion mobilised from Khazanah.

- MSME financing: RM40 billion for MSME-related loans and credit guarantees, with a focus on infrastructure, digitalisation and sustainability.

Work, education and training

- Progressive Wage Policy: full implementation in 2025 with RM200 million allocation but concerns over scalability.

- Education: major investments in preschool education and teacher training. Increased funding for skills development through TVET.

- Higher minimum wage: increased to RM1,700, aligned with labour reforms but regional disparities pose challenges.

Energy transition and low carbon development

- National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR): focus on renewable energy and decarbonisation, with RM305.9 million allocation.

- Carbon tax: introduction by 2026 for high-emitting sectors (e.g., steel, energy) to support low-carbon technologies.

- Solar energy: extension of Net Energy Metering (NEM) programme to promote rooftop solar installation.

Climate and disaster-risk management

- Disaster-risk management: RM13 billion allocated for flood mitigation, infrastructure maintenance and geological-risk management.

- Ecological Fiscal Transfer (EFT): increased funding for biodiversity conservation at RM250 million.

- Marine conservation: RM3.3 million to improve marine ecosystem management.

- Overview of Budget 2025

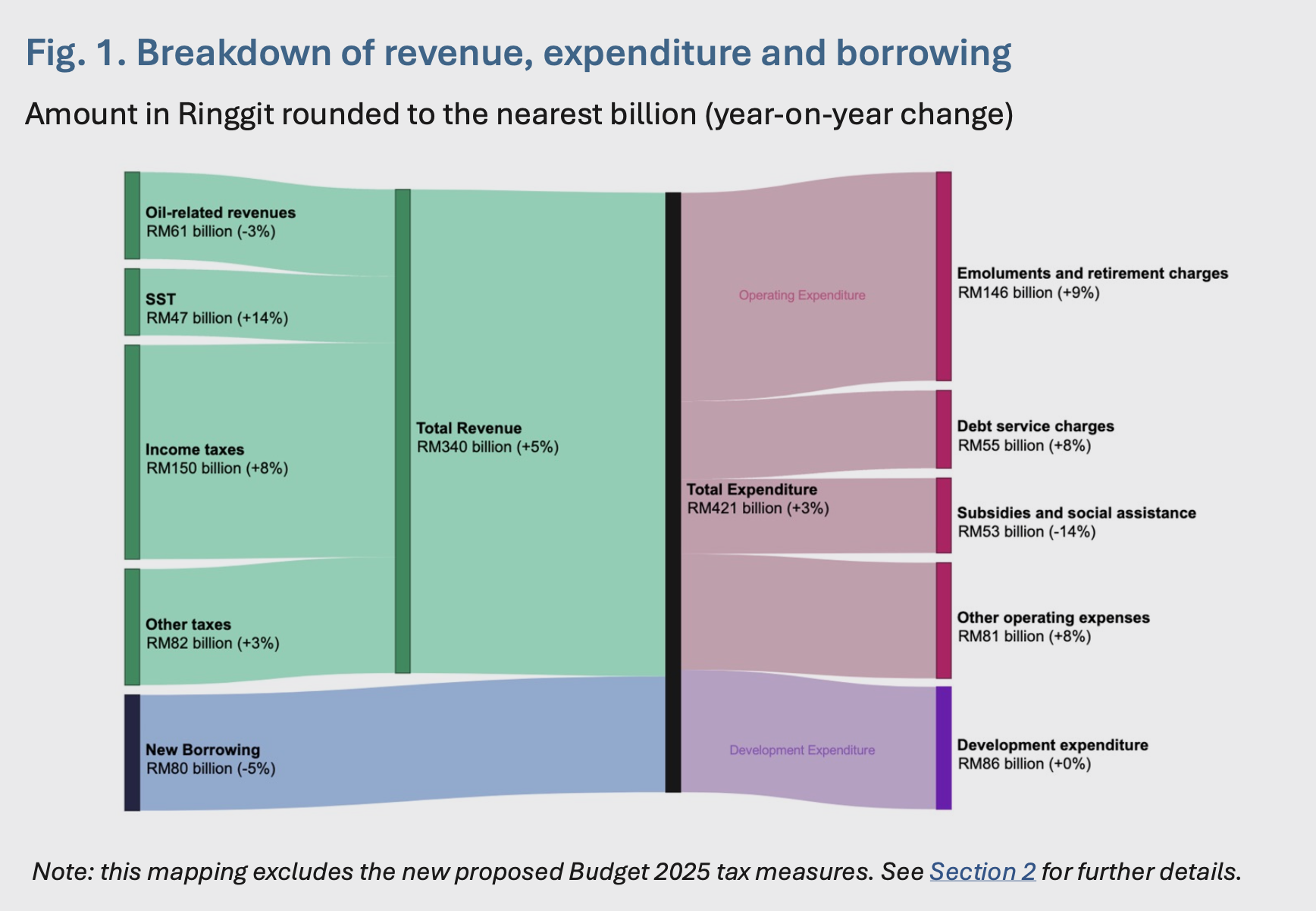

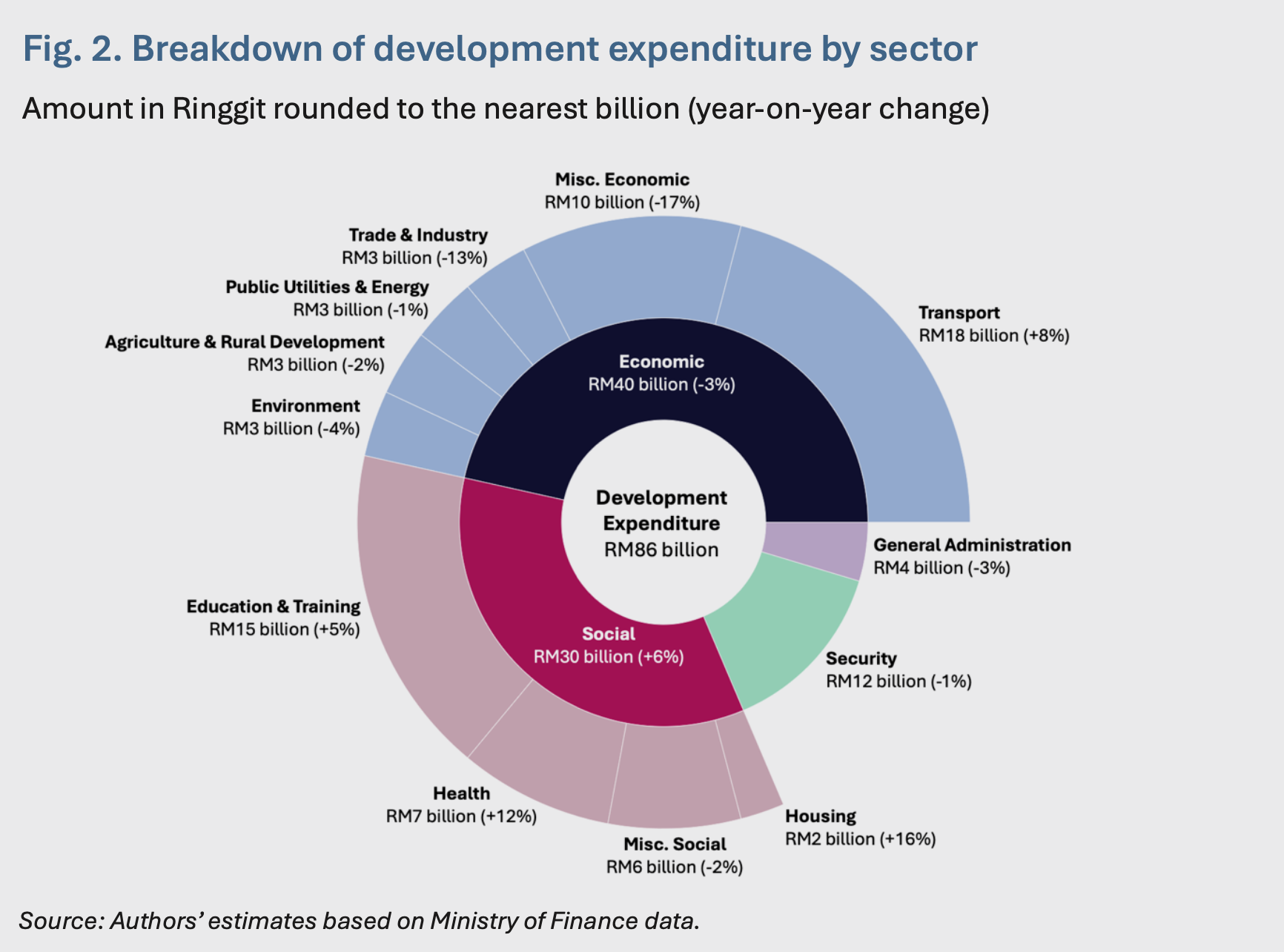

On 18 October, Prime Minister and Finance Minister Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim unveiled Budget 2025, centred on the theme of “Reinvigorating the economy, driving reforms, and prospering the rakyat”. The third MADANI budget, Budget 2025 had a total expenditure allocation of RM421 billion (3% year-on-year change), split between RM334 billion in operating expenditure (+4%) RM86 development expenditure (+0%) (see Fig. 1.). This is expected to be funded by RM340 billion in total revenue (+5%) and RM80 billion in new borrowing (-5%). Development spending remains about RM10 billion lower than 2023 and has decreased in relative terms over the past two years. Transport, education, and health make up the most significant non-security development expenditure items (see Fig. 2.). Ministry allocations also suggest that funding for certain ministries has been increased in line with Malaysia’s ASEAN chairmanship in 2025. [see section 2 on fiscal policy]

Several key points shape the policy direction of this budget. Revenue reforms are progressing but remain limited in scope, with SST basket expansion and a proposed new dividend tax [see section 3]. Subsidy reforms focus primarily on RON95, with limited changes overall. The introduction of a New Investment Incentive Framework (NIFF) should stimulate high-value activities, though allocations for NIMP 2030 are modest [see sections 4 and 5]. The upward revision of the minimum wage and full enforcement of the Progressive Wage Policy in 2025 signals the government’s commitment to incremental wage and labour markets reforms [see section 6]. On climate action, allocations for environmental and climate-related agencies have steadily increased, with Budget 205 outlining a commitment to implementing carbon pricing in high-emission sectors [see section 7]. The budget also reflects higher allocations for the Ecological Fiscal Transfer (EFT) initiative, while energy transition initiatives are broadly aligned with the National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR). Several incentives outlined in Budget 2025 could serve as precursors to the expected tabling of a law on Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage (CCUS) by year-end [see section 7].

2. Fiscal policy and new tax measures

Fiscal consolidation and expenditure

Budget 2025 introduces a negative fiscal impulse despite nominal spending increases. While the Budget 2025 allocates a record total expenditure of RM421 billion (a modest 3% increase from 2024), the continued reduction in the fiscal deficit from efforts to improve the federal government’s structural balance introduces a negative fiscal impulse. In other words, while Budget 2025 modestly expands nominal spending, aggregate fiscal support is tightening relative to the previous year as the government prioritises revenue growth over expanding total spending.

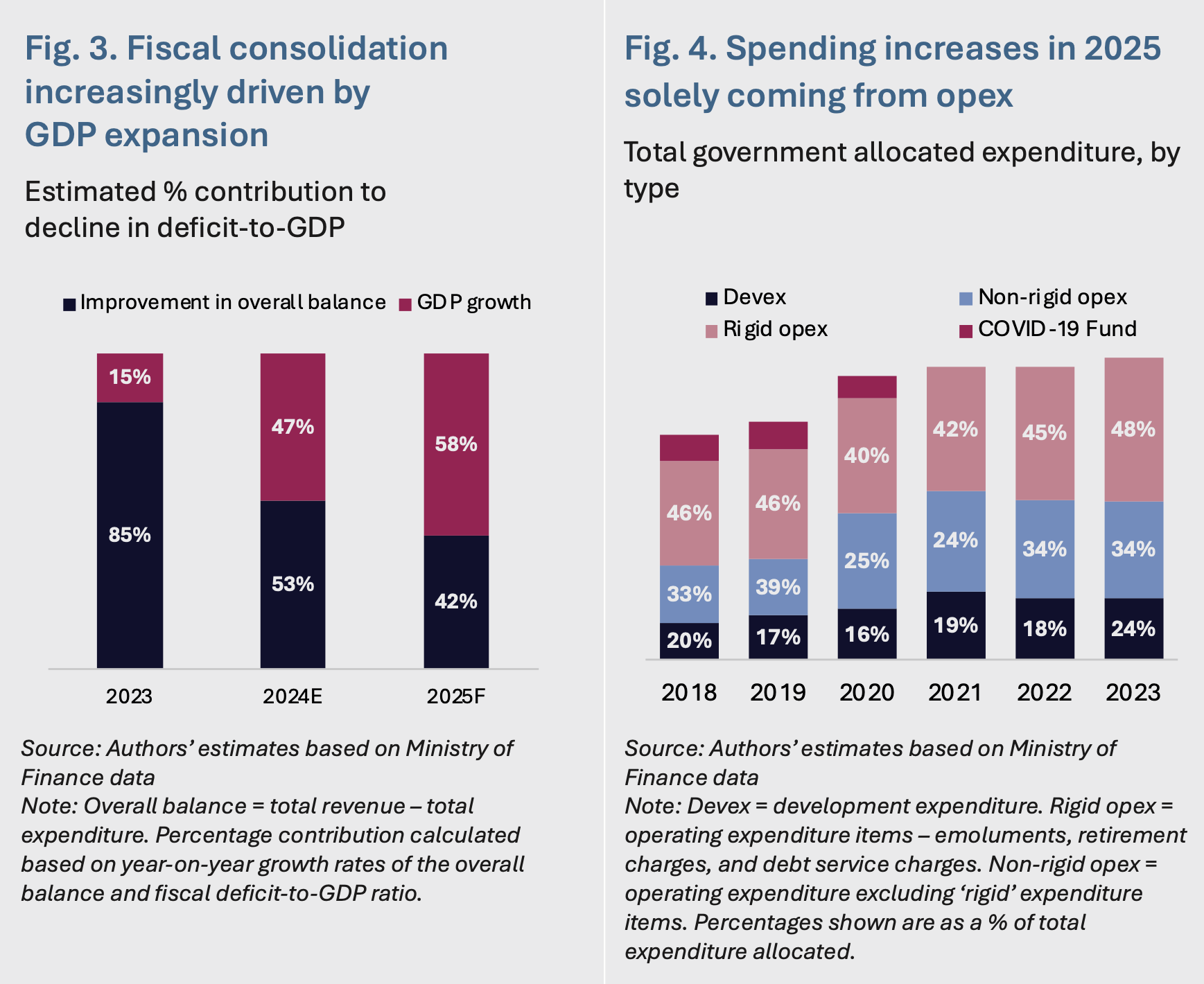

Fiscal consolidation progressing steadily through a “soft-fiscal tightening” approach but success hinges on continued above-average GDP growth (Fig. 3). Budget 2025 marks the third consecutive year in which the government approached consolidation through higher revenue growth while maintaining positive but modest spending increases. While this has made sustained progress in reducing deficit-to-GDP, our analysis suggests that the progress has been increasingly driven by GDP expansion rather than operating balance improvements (Fig. 3). In 2025, we estimate that only 40% of the decline in fiscal deficit-to-GDP is driven by improvements in the operating balance through revenue and expenditure measures.

This could mean that if the trajectory of above-average GDP growth falters, the pace of consolidation will fall short of targets set under the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 3.0% deficit-to-GDP by 2026-2028. As such, we assess that aggressive revenue measures could become necessary in the medium term ahead of the 2028 deadline.

The budget’s spending increase is driven entirely by higher operating expenditure, while development expenditure continues to shrink as a share for the second consecutive year. The rise in operating expenditure (opex) is largely attributed to growing emoluments and retirement charges, offset slightly by savings from reduced subsidy spending. “Rigid” spending, comprising of emoluments, retirement costs and debt-service obligations, now accounts for nearly 48% of total expenditure, up 8 percentage points since 2022, partly because of the planned implementation of the Public Service Remuneration System (SSPA). In contrast, development expenditure (devex), encompassing crucial investments in health, education and economic development, has continued to fall as a proportion of total spending since 2023 (Fig. 4). Ongoing fiscal consolidation could further constrain productive development spending, hindering the government’s ability to balance fiscal prudence with the bold investments necessary to achieve its strategic priorities under the Madani Economy Framework and other key initiatives.

Revenue and taxation

In Budget 2025, key proposed tax measures focus on broadening the SST basket and introducing limited dividend taxation. The proposals will expand the SST to cover a wider range of goods and services. This includes “luxury” food items and services, while “essential” food items remain SST-exempt. A 2% tax is also proposed to be imposed on dividend income for individuals earning more than RM100,000 from dividends. The budget also includes an expansion of tax reliefs in various categories, such as medical expenses, childcare, elderly care and sports activities. Excise duties on sugar-sweetened beverages will be increased, ostensibly to align with public health priorities, along with changes to export duties for crude palm oil to encourage downstream-processing activities.

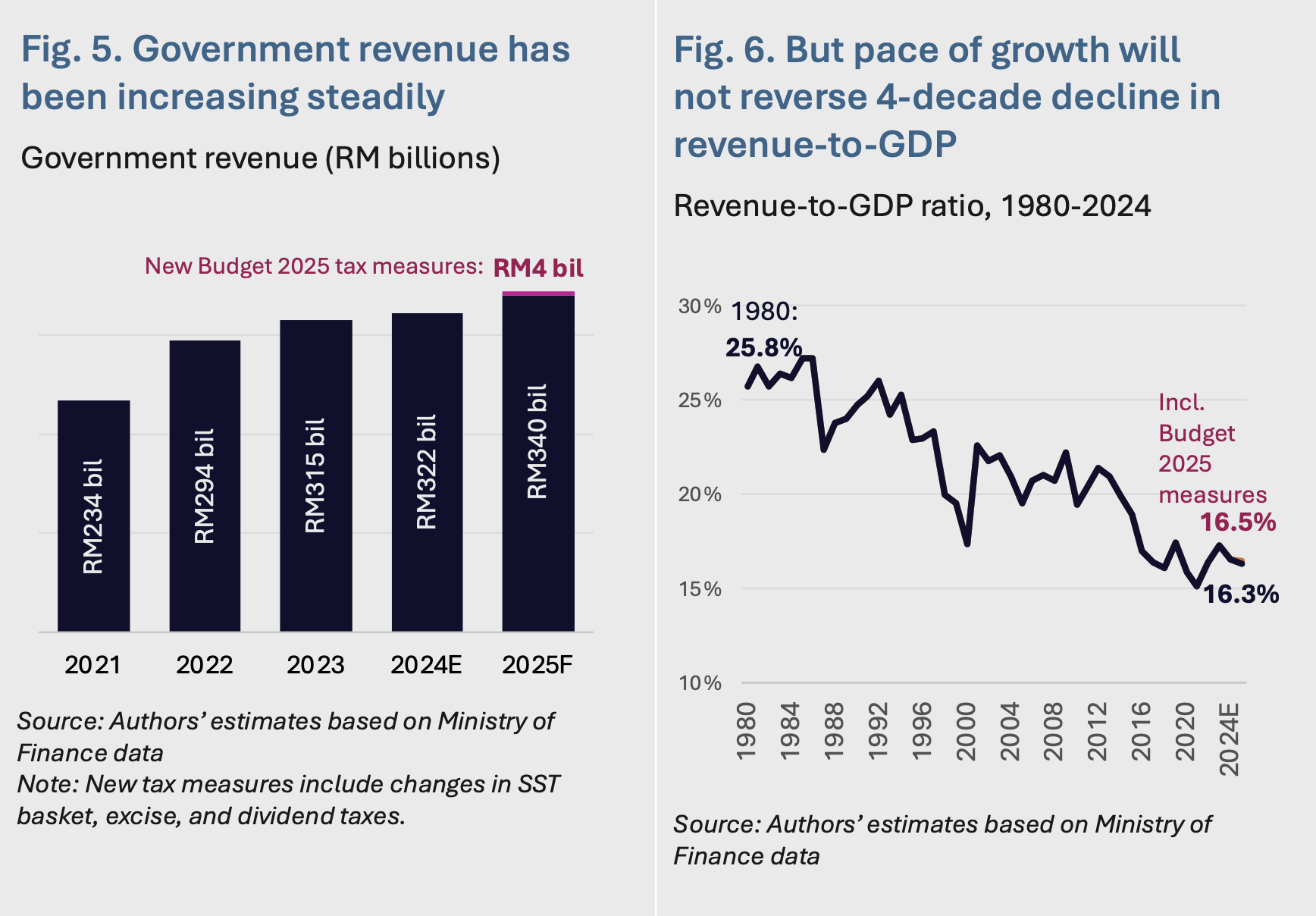

Government revenue projected to grow in 2024 and 2025 from greater collection of income taxes and higher SST revenue. Changes to the SST tax rate in 2024 and broadening of the SST basket in 2025 have increased indirect tax collection, while stronger economic activity has improved corporate and personal income tax receipts. Government revenue is projected to increase by RM17 billion in 2025 with a projected additional RM4.4 billion if proposed new tax measures in Budget 2025 are passed (Fig. 5).

Nonetheless, the current pace of revenue growth is still insufficient to reverse multi-decade erosion of the tax base (Fig. 6). Despite the introduction of new tax measures in 2024 and 2025, the long-term decline in the revenue-to-GDP ratio is expected to continue. In 2025, revenue-to-GDP ratios are estimated to be still at near four-decade lows even after accounting for RM4.4 billion expected to be generated by the new tax measures. Without more comprehensive tax reforms soon, we assess Malaysia’s tax base will continue to erode and revenue-to-GDP will continue to fall. This could place greater pressure on the government’s capacity to fund its policy priorities in the medium to longer term.

The limited dividend tax is a step towards more progressive capital taxation but unlikely to yield significant long-term revenue or meaningfully tax high-net-worth individuals. The proposed 2% tax on individual dividends exceeding RM100,000 – assuming a typical 4% dividend yield – requires an investment portfolio of about RM2.5 million to trigger the tax and would only generate RM2,000 in additional revenue per taxpayer at this lower limit. This high threshold for taxation, combined with the fact that high-net-worth individuals could easily circumvent it through portfolio diversification and wealth management strategies, dilutes the effectiveness of this measure towards both revenue and equity goals.

The SST is quickly approaching its limits in terms of basket expansion, rate and single-stage nature. Incremental adjustments to the SST design over the past two years by increasing the tax rate (2024) and expanding the basket of goods it covers (2025) have increased indirect revenue significantly. However, it may be reaching its current limits. As a single-stage tax, the SST inherently faces a natural ceiling in its revenue-generating capacity compared with multi-stage systems like a value-added tax (VAT). An SST basket expansion also risks eroding consumer demand as it would begin to cover goods and services deemed essentials, while further SST rate increases are already approaching levels that could suppress consumption and put upward pressure on prices. As such, in the medium term, the reintroduction of a VAT-style tax would offer a broader and more efficient revenue base by capturing value added at each stage of the production chain.

Laying the groundwork for tax reforms requires intensified and broader structural efforts. While initiatives, such as mandated e-invoicing, the rollout of a taxpayer identification number (TIN) and enhanced tax compliance enforcement are important steps towards modernising the tax system, these efforts must be expanded to build the necessary infrastructure for future wealth and capital gains taxation. This includes developing robust valuation mechanisms for assets and improving data collection on capital income. In the longer term, more comprehensive reforms – such as broader wealth or capital gains taxes – will be essential to share the tax burden with the top percentiles of wealth owners and ensure long-term revenue sustainability in line with the stated intention of Budget 2025. Without deeper and bolder reforms, current measures might risk being more symbolic than substantive in addressing wealth inequality and progressing on the equitable taxation of wealth.

3. Subsidies and social transfers

Targeted subsidies and RON95

Budget 2025 maintains the incremental shift away from broad-based blanket subsidies by moving to targeted subsidies for RON95 petrol, though the pace remains modest. Budget 2025 introduces plans to implement targeted subsidies by mid-2025, with the speech suggesting that the “top 15%” will no longer able to access subsidised RON95 petrol. Our back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that this would save about RM4 billion – similar to the amount saved from the diesel subsidy changes this year. However, this move stops short of a full subsidy removal, which could have realised fiscal savings of an estimated RM12 billion.

Nonetheless, the implementation of targeted subsidies for RON95 will face substantial challenges, particularly in real-time verification and preventing abuse. Statements from the Economy Ministry suggest that a two-tiered price system would be used and that identification of the “top 15%” will include non-income criteria like locality (proxy means testing) though the exact mechanism has not been finalised. We assess that the implementation of this mechanism could be complex and prone to leakages. This includes challenges related to real-time eligibility verification at the pump, along with risks of leakages through “proxy pumping” – where ineligible individuals leverage on intermediaries to access subsidised petrol. Without robust targeting and monitoring systems, this approach risks either generating lower-than-expected subsidy savings or creating significant exclusion errors.

In the medium term, policymakers could build on these efforts to outline a clear road map towards eventual float of RON95. This could entail gradual price adjustments through a managed float system to transition to a free float. Similarly, allowing phased exemptions like the removal of diesel subsidies combined with targeted transfers to low-income families through a “Budi Madani RON95” mechanism would help to support those most affected in the near term. Additionally, policymakers could strengthen the narrative around the redistribution of these savings for national development by earmarking a further portion of RON95 subsidy savings for investment in critical sectors, such as healthcare, education and social protection.

Cash transfers and social assistance

Budget 2025 continues expanding allocation to cash transfers and social-assistance programmes, representing some effort to redirect subsidy savings progressively. Allocations for cash-transfer programmes have grown from RM8 billion in 2023 to RM13 billion in 2025, signalling the government’s intent to reallocate subsidy savings into direct assistance. Flagship programmes like Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah (STR) and Sumbangan Asas Rahmah (SARA) top-up transfers are retained. There are increases in benefits for targeted cash aid provided by the Social Welfare Department (JKM), specifically for children and the elderly. These initiatives align with broader narratives around managing the rising cost of living and are complemented by the Budi Madani programmes, which aim to mitigate cost pressures in areas like diesel subsidies.

Transfer sizes for STR remains largely unchanged from previous years (Fig. 7). Instead, the expansion in social assistance is entirely directed towards the SARA top-up – a cash-like transfer restricted to essential goods at participating outlets. While this approach might ensure that funds are used for essential needs, it raises concerns about the flexibility and investment function of these transfers. By limiting household choices, the shift from cash to cash-like instruments could undermine the freedom of beneficiaries to spend and invest, reducing the effectiveness of these transfers as a poverty alleviation tool.

Current efforts also do not tackle legacy issues in social assistance programmes, such as high exclusion errors, work disincentives at income eligibility thresholds and fragmentation. The existing design of the STR programme will likely to continue to inherit large targeting errors – both exclusion and inclusion – from earlier iterations of national cash- transfer programmes (BSH, BR1M). Similarly, the core design of targeting income remains largely unchanged, preserving large work disincentives caused by high effective marginal tax rates at income thresholds of RM1,169 and RM2,500. These “benefit cliffs” can create work disincentives at the margin – something that is even more of a concern after the 2025 additions to the SARA programme that make these cliffs steeper at poverty line thresholds (Fig. 8). Additionally, the fragmentation between cash transfers administered by different ministries remains an issue. Consequently, reinvesting a larger portion of subsidy savings into improving the design, targeting accuracy and coordination of these programmes will improve welfare outcomes.

Social protection

Budget 2025 introduces incremental improvements to social-protection coverage, focusing on extending existing measures. On the pension front, the government has increased matching incentives for the i-Saraan voluntary retirement savings programme from 15% to 20%, encouraging informal workers to build retirement savings. Similarly, i-Suri, which targets housewives, maintains a 50% matching contribution incentive to enhance their financial security. Additionally, the budget introduces a phased mandatory EPF contribution for non-citizen employees, gradually bringing them into the formal pension system. On the social insurance side, the continuation of the Self-Employment Social Security Scheme (SKSPS) and Perlindungan Tenang microinsurance initiative aims to increase coverage to non-standard workers.

However, Budget 2025 does not introduce a comprehensive overhaul necessary to address coverage gaps posed by an ageing population and an expanding informal economy. The social-protection system remains primarily designed around formal employment, leaving millions of informal workers, including those engaged in home production, without adequate protection against risks, such as unemployment, illness or old age. Many initiatives in Budget 2025, such as i-Saraan and i-Suri, rely on voluntary contributions, which tend to attract a self-selection of individuals already more inclined to save or plan for retirement rather than supporting those most in need of protection. These programmes also still depend heavily on income generation from formal employment, which excludes informal workers and those performing unpaid care and domestic work.

Future efforts should focus on establishing a more integrated, inclusive social-protection system that can adapt to economic risks and demographic changes. This entails taking a life-cycle approach to social protection, ensuring adequate coverage from early childhood through to old age. Likewise, integrating STR/SARA with JKM child/elderly assistance into a broader social-protection framework could serve as the foundation for a national social pension and child benefit system in the medium term. Such integration should bridge social services with transfers, expanding investment in community-based care infrastructure and services. By investing in these areas, Malaysia’s social-protection system could comprehensively cover a wider range of vulnerable populations, including informal workers, caregivers and the elderly – enabling broader economic participation, improving economic growth and promoting social equity.

4. Industrial development and competitiveness

Budget 2025 strengthens the government’s strategic approach to promoting high-impact investments through the New Investment Incentive Framework (NIIF). Scheduled to be launched in early 2025, NIIF aims to review and streamline investment incentives to enhance economic complexity, high-skilled talent development and supply chain resilience. Coupled with an investment fund of RM1 billion, NIIF is crucial for translating the Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry’s (MITI) National Investment Aspirations into action. This represents a shift from past approaches of offering a broad range of incentives without regard for economic multipliers, domestic spillovers and sustainability.

NIIF, if implemented well, could be the missing piece in Malaysia’s industrial policy. While details remain limited, the budget speech suggests targeted incentives under NIIF for strategic sectors and less developed states. This lines up well with Action Plan E3.1 in the New Industrial Master Plan (NIMP) 2030 to evaluate investment parameters amid calls to review the Promotion of Investment Act 1986. An “outcome-based tax incentive package” for supply chain resilience is also proposed. These initiatives are a promising step towards developing an ecosystem of performance-linked incentives, a feature of successful industrial policy models worldwide. In this way, NIIF could encourage greater technology transfer as well as forward and backward linkages between local and multinational corporations, thereby maximising industrial upgrading and value addition. However, clarity is needed on NIIF’s alignment with related policies, such as NIMP 2030.

Spending on NIMP 2030 has been relatively modest, falling short of the RM8.2 billion commitment. Budget 2025 allocates RM200 million for the master plan through the NIMP Industrial Development and Strategic Co-Investment Funds to promote technology adoption and mobilise financing in priority sectors. This is only one-sixth of the average annual allocation of RM1.2 billion needed to fund NIMP 2030 over the next seven years, raising questions about the government’s ability and readiness to begin operationalising the long-term plan. Despite this, ancillary initiatives, such as RM100 million for training in NIMP 2030-linked activities (electric vehicles, aerospace and AI), have been announced to support implementation. Budget 2025 also upholds NIMP 2030’s ethos of crowding-in private investment, evident in Khazanah’s RM1.2 billion for semiconductor investments and talent development. Nevertheless, as NIMP 2030’s institutional structure becomes fully formed under the new Delivery Management Unit, accelerated funding will be needed to meet the master plan’s targets.

Budget 2025 stresses the importance of strengthening the electrical and electronics (E&E) ecosystem through a holistic focus on hard and soft infrastructure. Several projects are outlined, including the development of Kerian Integrated Green Industrial Park in Perak and the expansion of Kulim Hi-Tech Park within the northern semiconductor cluster (see Appendix A). Funding for specialist AI-themed higher education increased to RM50 million, supporting Universiti Sains Malaysia’s semiconductor R&D. For maximum impact, these initiatives must be accompanied by efforts to increase university-industry collaboration to ensure local engineering graduates are industry ready.

However, an important programme left out of Budget 2025 is the National Semiconductor Strategy (NSS). Introduced provisionally in May 2024, NSS outlines strategies to develop national front-end capabilities in the semiconductor industry while solidifying the country’s position in the back-end segment amid global geopolitical shifts. NSS calls for RM25 billion in fiscal support to increase sectoral R&D and talent development – critical areas for Malaysia to advance up the value chain. While the budget speech lists the NSS as a “policy lever” to realise Ekonomi Madani, it did not receive any budgetary allocation, leaving uncertainty about when this support will materialise. In the near future, the government should release the full NSS, along with a timeline for implementation and financing to provide policy clarity, given the industry’s significant contribution to trade, investment and output.

The government acknowledges Malaysia’s declining global economic competitiveness and aims to boost its ranking in line with Ekonomi Madani. In 2024, Malaysia dropped to 34th place in the World Competitiveness Ranking because of weaknesses in efficiency and business legislation. Budget 2025 tackles these challenges, outlining efforts to improve the ease-of-doing business, including launching the InvestMalaysia one-stop investor portal, consolidating overlapping promotion agencies and establishing a facilitation centre in Johor to streamline processes in the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone. Initiatives like these should continue to promote trade facilitation and a seamless end-to-end investment environment, synonymous with NIMP 2030’s enablers.

Finally, Budget 2025 boosts MITI’s opex by nearly 50% for two major events with potential spillovers – World Expo 2025 and Malaysia’s ASEAN chairmanship (Fig. 10). The World Expo in Osaka is expected to generate RM13 billion in exports and investments for hundreds of participating Malaysian companies. Malaysia’s chairmanship will allow it to lead key regional developments, including the ASEAN Community Vision 2045. Effective management of this chairmanship is essential to maximise opportunities for greater regional integration, higher intra-ASEAN trade and a more coordinated strategy for Global South engagement. A whole- of-government effort is needed for successful leadership and accordingly, the chairmanship appears as a line item in the estimated 2025 expenditures for MITI and 26 other ministries, chiefly Foreign Affairs (Fig. 10).

Overall, Budget 2025 demonstrates the Madani administration’s continued commitment to industrial development but increased funding and strategic alignment with existing frameworks are crucial. NIMP 2030’s centrality in industrial policy is reflected throughout the budget, seen in public infrastructure spending and private investment, particularly for the E&E sector. However, significantly more funding is needed to achieve long-term targets in value addition and high-skilled job creation – and this should include the timely implementation of the NSS. Further, NIIF is a welcome move towards targeted, outcome-oriented incentives but it must be aligned with NIMP 2030 to enhance industrial capacity and competitiveness. Lastly, Malaysia’s ASEAN chairmanship offers a timely opportunity for regional leadership but sustained efforts to drive integration and collaboration are needed beyond 2025 to maximise benefits.

5. MSMEs, entrepreneurship and innovation

Budget 2025 aims to recalibrate its policy focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which incentivises capacity building and lending as opposed to cash grants. Overall, RM40 billion is allocated for SME-related measures, which largely consist of loans, credit and financial guarantees. The figure is RM4 billion lower than in Budget 2024. Some big-ticket items, such as RM50 million for the digital matching grant and RM3.8 billion lending facility from Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) will continue to support the SME transition towards digitalisation and automation, with a focus on agri-food and sustainability. Tax incentives for purchasing equipment needed to implement e-invoicing will support the migration of MSMEs towards this system, laying the groundwork for future changes, such as the goods and services tax (GST).

The government continues to provide a slew of credit financing and guarantees with a total allocation of RM40 billion targeted at microenterprises and SMEs (MSMEs) through various agencies. Notably, the government maintains its credit guarantees for SME financing through SJPP, with RM20 billion to support lending activities. Moreover, nearly RM10 billion has been earmarked for MSME lending through TEKUN, BSN and Bank Pembangunan Malaysia (BPMB), with a focus on infrastructure, digitalisation, tourism, logistics and renewable energy, highlighting efforts to encourage MSME participation in these sectors. Compared with previous budgets, there is relatively more focus on credit guarantees and matching grants rather than direct grants for MSMEs, indicating a shift towards more efficient allocations for MSME development in line with a broader post-pandemic recovery.

The full stamp duty exemption on loan and financing for MSMEs and an increase in the micro-loan limit under the Micro Financing Scheme to RM100,000 is likely to support credit demand among smaller enterprises. MSME loan demand has been on an upward trend, with monthly loan applications from MSMEs increasing from 24,135 in 2022 to 29,126 in 2024, according to BNM data. Encouragingly, this expansion in lending facilities has been buoyed by stronger MSME GDP and export trends, which rose 5.0% and 4.5% respectively in 2023, making up 39.1% of total GDP and 12.2% of total exports. Nevertheless, these numbers remain below the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP) targets for MSMEs of 45% of GDP and 25% of total exports by 2025. In this vein, SME export empowerment measures, such as the Khazanah Mid- Tier Company Programme and the Exporter Sustainability Incentive by Exim Bank, may boost SME exports to developed markets, while a RM40 million matching grant to assist exporters in promoting local products in new Global South markets is likely to broaden the exposure of Malaysian products overseas. Nevertheless, further consultations with stakeholders might be necessary, particularly easing customs and paperwork requirements which are generally more onerous for them to comply with.

The proposed 2% tax on dividend income above RM100,000 might have mixed results for MSMEs and government revenue. From a revenue collection perspective, by targeting dividend income, it effectively closes a loophole where MSME owners typically prefer to earn income from company dividends as opposed to paying themselves a salary as they are currently not taxed. This, therefore, broadens the tax base and narrows the gap between wage and passive income earners. However, given that most MSME are substantially smaller compared with public-listed firms, most of the additional tax revenue is likely to come from a small fraction of individual shareholders who receive dividends of more than RM100,000 annually.

Nevertheless, this policy effectively creates double taxation for business owners, as they are taxed both at the corporate and individual income level. Similar systems exist in developed markets like France, Canada, the United States and Japan where some form of double taxation on investment income targets high net-worth individuals. While this may encourage investors to move funds to more dividend tax-friendly markets – especially withforeign income exempt until 2036 – it could also encourage owners to reinvest profits into their businesses rather than paying themselves a dividend, indirectly supporting balance-sheet growth. Ultimately, despite issues of double taxation, the policy helps to level the playing field between wage and dividend earners, echoing past statements by the Madani administration to create a more redistributive economy.

Lastly, the carbon-tax on steel and iron could have economic implications for sectors that utilise these resources intensively. While this tax is a step in the right direction in limiting carbon emissions and the promotion of emission-saving technologies, this could have inflationary impacts on downstream sectors. For MSMEs in these sectors, rising input costs could reduce profit margins or otherwise necessitate price increases, which might, in turn, slow growth in industries sensitive to price fluctuations, like construction. Nevertheless, due to major markets, such as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), Malaysian steel exporters may face more equitable conditions on the export side. On a positive note, this could drive the adoption of green steel technologies.

6. Work, education and training

Work and labour markets

Budget 2025 announces the full implementation of the Progressive Wage Policy (PWP) to be enforced in 2025, with an allocation of RM200 million. The PWP, first piloted in June, is designed to link wage increases to skills development and career progression, particularly targeting workers earning below RM5,000 a month in local companies (for a full summary see ISIS Malaysia’s PWP policy brief). It aims to address wage stagnation and improve labour market outcomes by encouraging employers to raise wages while incentivising skills development among the workforce.

The move to full implementation is encouraging but concerns remain. The RM200 million allocation to the PWP is relatively small. Our earlier estimates suggest that full implementation, with conservative coverage assumptions, suggests the PWP would could cost nearly RM925 million annually just in outlays – almost five times the current allocation. This limited funding raises concerns about the programme’s overall scalability and ability to create a meaningful impact on wage levels across various sectors in the long term. Moreover, implementing the full programme without public dissemination of the pilot results and/or announcement of adjustments to the design of the PWP creates further risks.

Policymakers could consider outlining multi-year timelines for PWP’s future to move the needle on wages and skills development. This should include a phased expansion of coverage across more worker and firm types and a gradual move towards mandatory compliance. Likewise, deepening integrating PWP with existing skills training and education programmes, including TVET, could further support its ability to raise wages, encourage skills development and labour mobility that ensure sustainable wage growth and streamline implementation.

Budget 2025 announces a further increase in the minimum wage to RM1,700, following the previous adjustment to RM1,500 in 2022. This continued push aligns with the government’s goal of progressing on labour market reforms and strengthening workers’ wages. Our estimates suggest that this figure represents approximately 60% of national median wages, which brings Malaysia’s wage floor in line with international guidelines for adequate minimum wage levels.

However, the benefits of a higher minimum wage could be limited without strengthening enforcement mechanisms. Stakeholder engagement with workers’ representatives suggests that non-compliance and wage theft remain issues in certain sectors and regions even before the minimum wage increase, in part because of limited enforcement capacity. Additionally, the single national wage floor may not account adequately for significant regional wage disparities. For example, back-of-the-envelope calculations using a 60% median wage benchmark suggest that Kuala Lumpur could require a minimum wage closer to RM2,500 – while the new RM1,700 wage might be too high for lower-cost regions. This mismatch could create compliance challenges and impact on employment elasticities in lower-wage areas.

Education and training

Allocations to the Education Ministry are directed at addressing the two largest pain points in the education system – unequal access to pre-primary education (Fig. 11) and teacher quality (Fig. 12) RM150 million has been earmarked for preschool education, an increase of more than 400% from the previous year. RM136 million has been allocated for teacher competency development programmes to reach the target of 96% of teacher trainees to achieve a minimum honours result in the bachelors of teaching programme.

TVET remains in the limelight with the largest ever allocation (Fig. 13) and the coordinated efforts of the Education, Higher Education and Human Resource Ministries. To support the National TVET Policy, RM238 million has been allocated to the Education Ministry for TVET. The Higher Education Ministry has set the target to increase the number of places for polytechnics and community colleges to produce TVET graduates to 129,000. Coupled with efforts to increase the economic complexity and attracting high-value investments, the demand for highly skilled labour is expected to grow. Thus, it is crucial to expand the proportion of highly skilled TVET graduates to align with industry needs (Fig. 14).

Expansion of skills development programmes is necessary to prepare workers for the future of work with disruptive technologies, such as generative AI, entering the scene. RM1.8 billion has been allocated to the Human Resources Ministry, representing a 24% increase from 2024 and the greatest increase for the ministry in a five-year period. Out of the RM800 million allocated for devex, RM500 million is for skills development. Another RM242 million has been allocated for labour and employment management, more than 600% increase from the previous year.

Scholarship and sponsorships have been expanded compared with 2024. RM502 million has been allocated to the Education Ministry and RM220 million to the Higher Education Ministry for scholarships and sponsorship programmes. Last year’s figure was RM21 million.

7. Climate, energy and environment

Introduction and overview

Budget 2025 continues to prioritise environment and climate action, with a particular focus on energy transition, biodiversity, environmental management and disaster-risk management. While many initiatives align with Malaysia’s environmental and climate policies, there is a noticeable shift towards the green economy, emphasising energy transition and leveraging on emerging technologies, such as renewable energy, low-carbon technologies, and carbon capture and storage (CCS). The government has introduced various fiscal incentives, including the Green Technology Financing Scheme (GTFS), NETR funding and continuation of Low Carbon Transition Facilities – in which government and private financial institutions support some of the schemes. The much-anticipated carbon pricing is expected to accelerate further this transition. Most energy and green transition initiatives will be funded by the private sector and financial institutions, while natural resource management and disaster-risk management will rely on public funding. About RM14.9 billion is allocated for key climate and environment initiatives under government expenditure, in which nearly 87% is earmarked for disaster-risk management, mostly on flood mitigation, infrastructure upgrade and drainage maintenance (Fig. 15).

The government’s allocation for environmental and climate-related agencies has steadily increased since 2021, with a slight rise in Budget 2025, reflecting a growing commitment to sustainability. Estimating the government’s total allocation for the environment and climate sector is difficult because of the cross-cutting nature of these issues and the absence of climate or environment budget tagging in Malaysia. Additionally, cabinet reshuffles and ministerial rebranding have complicated efforts to quantify and map these allocations. Nevertheless, official reports and data indicate a steady increase in funding for climate and environmental ministries since 2021 (Fig. 16). In Budget 2025, allocations for the Ministry of Energy Transition and Water Transformation (PETRA) and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) rose slightly, from RM7.13 billion in 2024 to RM7.22 billion. Although modest, this increase reflects a broader shift under the Madani administration, whichnotably raised allocations for these ministries between 2023 and 2024, hitting a record high. This trend highlights the growing commitment to addressing climate change and promoting environmental sustainability.

Since its announcement in the 12MP in 2021, the government has finally committed to implementing carbon pricing in high-emitting sectors but more information is needed on its design and implementation to gauge its effectiveness. By 2026, a carbon tax will be implemented in the steel and energy sectors to accelerate decarbonisation and adoption of low-carbon technologies. This aligns with Malaysia’s climate and energy policies, as carbon pricing is one of the catalytic initiatives under the National Climate Change Policy 2.0 and serves as a policy lever in the National Energy Transition Roadmap. The timing is also crucial, as it positions Malaysia to respond to the EU CBAM, set to take effect by 2026. Encouragingly, the carbon tax is expected to fund research into green technologies, rather than merely serving as a revenue-generating mechanism for the government. However, it remains unclear to what extent the carbon tax will function as a “first-best policy instrument” – providing strong market signals and sufficiently able to incentivise industries to adopt low-carbon technologies and innovations. Further details are desired – regarding the carbon price and its integration (if any) with an emission-trading scheme, which is stated as a potential scope under the Climate Change Bill.

Climate adaptation has yet to receive a specific focus and is embedded sporadically with indirect attribution across sectors, such as disaster-risk management, agriculture and conservation. While large allocations have been made for flood mitigation, infrastructure repairs and disaster aid, it is unclear to what extent climate components are considered and addressed under these initiatives. Another gap is related to a mismatch between policies and practice. In various plans and policies, including 12MP, National Physical Plan 4 and the recently launched National Climate Change Policy 2.0, the government has consistently recognised the importance of shifting from grey infrastructure towards more holistic approaches, such as nature-based solutions, resilience cities and integrated flood management that could provide co-benefits and address multiple climate hazards. However, yearly funding is still concentrated towards structural and heavy engineering solutions, which are often costly and economically inefficient, given the tight fiscal space. This indicates the legacy issues of the silo approach to disaster management. For instance, flooding is still viewed as the sole responsibility of the Department of Irrigation and Drainage, rather than adopting integrated, cross-sectoral solutions.

The government continues to map its budget with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), increasing allocations for 2025, though full SDG alignment remains unclear. Since 2022, the government has started the exercise of mapping the budget with SDGs for operating and development allocation. Based on official reports, all SDGs received an increased allocation in 2025, compared with 2024 with the biggest allocation under education (SDG 4) and notable rises in poverty eradication (SDG 1), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), and climate action (SDG 13). While the alignment shows positive trend, it remains unclear if the budget as a whole is SDG compliant in terms of considering the trade-offs across all SDG pillars, goals and targets. The government also maintained funding for the All-Party Parliamentary Groups on Sustainable Development Goals (APPGM-SDG) to support the localisation of SDGs. The RM20 million allocation reflects the commitment to the bipartisan SDG initiative, marking the sixth consecutive year of funding since 2020.

The 2025 Budget reflects a gradual improvement in Malaysia’s climate action and environmental policies. While there are some new initiatives, it remains largely a ‘business as usual’ approach, particularly in disaster risk and environmental management. On a positive note, the introduction of a carbon tax marks a significant step, even though the scope is currently limited and details are still forthcoming. This move sets a potential precedent for future policies that could price pollution and resources across sectors like natural resources, water, and biodiversity, encouraging behavioural changes in business and society. While Malaysia has been offering various financing instruments to attract investment for energy transition and the green economy, its climate priorities must extend beyond green branding to attract foreign direct investment and boost GDP. There is a need to view climate change and environmental challenges through a sustainable development lens, while recognising the risks to human rights, development gains, trade, productivity and public health. This will require the government to start prioritising more adaptation efforts.

Environmental and natural resources management

This section highlights key initiatives and highlights from the budget on three broad themes: biodiversity conservation, environmental and river management, and sustainable agriculture and commodities. The list of these initiatives is in Appendix B.

Biodiversity conservation

The annual budget continues to emphasise on the protection of natural assets, as reflected by the positive trend in allocation for the Ecological Fiscal Transfer (EFT), Malaysia’s flagship conservation initiative. Providing incentives for state governments to implement biodiversity conservation projects, the EFT allocation for 2025 was increased by RM50 million, from RM200 million to RM250 million, continuing the trend of consistent annual increases since its inception in 2019 (Fig. 17). Additionally, the government has introduced a performance- based criteria to address implementation challenges that has been associated with EFT, with 50% of the allocation now linked to state governments performance in implementation and expenditure. To enhance effectiveness, the ecological criteria still need to be clearly defined in terms of access and utilisation of these funds, and greater transparency in communicating the actual on-ground impact of these funds. Institutionalising the EFT within policy and legal frameworks remains essential for ensuring long-term effectiveness and continuity.

Despite this positive move and the continual increase in allocation, the amount is still unlikely to compensate fully state governments for the opportunity costs associated with land-based revenue. There is a need for greater emphasis in incentivising private capital allocation towards conservation through more innovative financing instruments. These could blended financing, exploration of high-quality biodiversity credits, nationwide payment for ecosystem services, all of which align with the objectives of the National Policy on Biological Diversity 2022-2030 (NPBD) and Malaysia Policy on Forestry 2021. Additionally, regulatory instruments such as biodiversity compensation and no net loss, that is already stated in the National Physical Plan 4, could create an enabling environment to stimulate supply and demand in conservation projects.

Other planned conservation allocations focused on forest restoration, enforcement and ecotourism. To complement forest-protection efforts, the government allocated RM90 million for forest restoration. However, more clarity is needed on prioritising specific regions, habitat types and reforestation activities. The government has also expanded the Community Rangers Programme to combat poaching and illegal activities in forested areas by increasing the number of rangers to 2,500 under the Biodiversity Protection and Patrolling Programme and Smart Patrol initiative. This includes the involvement of Malaysian Armed Forces and Royal Malaysian Police veterans, Orang Asli and community rangers in the permanent reserved forests within the Central Forest Spine.

Small emphasis was given on marine conservation, but a larger budget is needed to support critical marine ecosystems and coastal communities. A total of RM3.3 million is dedicated towards marine conservation to enhance the management of marine protected areas. While the inclusion of marine ecosystems is a positive step, the amount remains disproportionately small compared to terrestrial conservation. Considering the critical role that marine ecosystems play in supporting national food security, the livelihoods of coastal communities and resilience of Malaysia as a maritime nation, a larger allocation is necessary to meet both conservation and social objectives. Future budgets could include allocation for a more holistic interventions, such as seascape approach to managing marine conservation areas, Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM) and fish stock recovery; in line with the policy objectives of the NPBD, National Physical Plan 4 and National Coastal Physical Plan 2.

Environmental and river protection

In terms of environmental management, the emphasis remains on the rehabilitation, conservation and protection of rivers. An allocation of RM10 million has been made to expand the Program Denai Sungai Kebangsaan to include Sg Anak Bukit in Kedah, Sg Pegalan in Sabah, and Sg Etanak in Sarawak. This initiative encompasses community river clean- up programmes and communication, education and public awareness (CEPA) efforts. The Program Denai Sungai Kebangsaan was first introduced in 2020 to increase public involvement in river conservation and serve as “eyes for the government” in maintaining river health.

In addition to upgrading of sewage infrastructure, stronger efforts are needed to tackle both point and non-point source river pollution. The government has allocated RM693 million to upgrade regional sewage treatment plants and construct a sewage pipeline network to curb water pollution in Sg Kim Kim, Johor. The modernisation of the sewerage system has been a key priority under 12MP. While this initiative addresses sewage-related pollution, a more strategic and concentrated effort is needed to curb illegal chemical dumping, especially given the recurring episodes of odour pollution in many rivers across Johor. While it is logical to focus efforts on Johor, which has the highest number of polluted rivers in the country, continuous efforts should also be expanded to other river basins nationwide. Currently, 25 rivers monitored by DOE are classified as polluted under the Water Quality Index.

Enforcement capacity at the federal level has been strengthened with specific allocation, but sub-national authorities also require stronger enforcement support. The government has allocated RM3.9 million to the Department of Environment (DOE), enhancing its capacity to enforce the Environmental Quality Act 1974. While this will strengthen enforcement capabilities, DOE can only enforce pollution regulations on factories and similar industrial activities because of its legal mandate under the EQA. Therefore, stronger enforcement is necessary for other agencies at the sub-national levels, such as local authorities, particularly sewage overflows and illegal dumping sites within municipalities.

Sustainable agriculture and commodity

Strengthening domestic standards and promotion campaign remains the focus in the palm oil sector but closing information gaps across the supply chain can better solidify Malaysia’s sustainability credentials. RM50 million has been allocated to continue enhancing the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standards, which were revised in 2022, and RM15 million has been set aside for efforts to combat negative perceptions at the international level, specifically European misinterpretation. The former is expected to strengthen Malaysia’s sustainability credentials and align with EUDR requirements, particularly if improvements focus on ecosystem standards, such as enhancing geolocation capabilities within the MSPO trace system and achieving full traceability from plantation to export. While the allocation for addressing negative palm oil perception is understandable, these funds might be better utilised in addressing information gaps to provide evidence-based communication on Malaysia’ssustainable palm oil supply chain, particularly in relation to deforestation. For instance, establishing geospatial data on forest areas corresponding to MSPO’s deforestation-free cutoff date (31 December 2019) and the EUDR’s cutoff date (31 December 2020) could help reconcile differences in forestry and supply chain data between the EU and Malaysia . Our neighbour, Indonesia, is already undertaking such efforts in cooperation with the European Commission.

Close to RM80 million has been allocated for a sustainable agriculture to enhance food security, market competitiveness and the resilience of smallholder farmers. In addition to the continued promotion of the voluntary programme for good agricultural practices (GAP), this budget marks the first time that RM49 million has been allocated for a sustainable agriculture agenda. This includes the development of agrifood sustainability and soil conservation programmes in line with the National Agrofood Policy 2.0. There are also provisions to support farmers through the Agricultural Disaster Fund (TBP), though the RM25 million allocation is 50% less than previous year’s budget.

Energy transition and low carbon development

Energy transition initiatives in Budget 2025 are aligned with the overarching framework established by NETR. The announcements in Budget 2025 can be categorised broadly as extensions of measures outlined in the previous budget, support for policies that have been catalysed by NETR over the past year, highlights of ongoing projects or a teaser of signposted initiatives in the road map. In essence, the energy transition focus of Budget 2025 appears to be on ensuring continuity for current pathways and bridging the period to the upcoming 13th Malaysia Plan (13MP), which may see enhancements to decarbonisation approaches.

PETRA received RM4.95 billion or 1.2% of the total budget, primarily for water-related initiatives. The allocation is on a par with 2024 after the energy and water portfolios were separated from the previous Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Climate Change. Of the amount, 93% is for development, ranking it as the ministry with the ninth highest devex. However, it is worth noting that only 3% of PETRA’s devex is specifically for energy – mainly for Sabah’s electricity supply – while initiatives related to water supply and flood mitigation, as well as river, coastline, waste and dam management, received the bulk of the funds.

The budget specifically earmarked for NETR implementation falls under the purview of the Ministry of Economy (KE) with RM305.9 million allocated in 2025 compared with RM100 million in 2024. The total of about RM400 million over two years makes up 20% of the RM2 billion committed in NETR and Budget 2024 as accumulated seed funding for the National Energy Transition Facility. There is, however, limited information about the utilisation of these funds. Furthermore, this quantum is still far short of NETR’s minimum estimation of RM210 billion in transition financing required up to 2029. In Budget 2024, the government called upon financial institutions to facilitate the shift to a low-carbon economy by unlocking RM200 billion in financing. While the overall response appears to have been positive, consolidated and transparent reporting would enable better planning and optimal allocation of funds.

Budget features a plethora of financing schemes aimed at facilitating low-carbon transition initiatives for corporations and SMEs. These include RM1 billion under the Green Technology Financing Scheme 5.0 by the Malaysian Green Technology and Climate Change Corporation, RM1.3 billion under the High Tech and Green Facility Scheme and RM600 million under the Low Carbon Transition Facility by BNM, RM39 million under the Green and Sustainable Business Financing by the Malaysian Industrial Development Finance and RM500 million under the Renewable Energy and Energy Transition Programme by Bank Pembangunan Malaysia.

The cross-cutting nature of the energy transition, illustrated by the overlap in the roles and distribution of budget funds to PETRA and KE, spotlights the importance of alignment throughout all levels of implementation. The National Committee for Energy Transition and National Energy Council play a crucial role in coordinating a whole-of-nation approach to realise the goals of NETR, not just between the ministries responsible for energy and the economy, but also across the broad spectrum of stakeholders from other ministries, government agencies, regulators, industry players, civil society and the public. In this regard, it is unfortunate that the National Energy Knowledge Hub, an NETR Technology and Infrastructure initiative, has yet to materialise. Slated as a one-stop centre for energy transition data and programmes, this low- hanging project would go a long way in consolidating information on the progress of NETR as well as streamlining public access to it.

In line with efforts to accelerate the adoption of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, the Net Energy Metering (NEM) scheme has been extended from 31 December to 30 June 2025. First implemented in 2016, NEM allows consumers to utilise energy from their rooftop solar installations and export any excess to Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB). The current iteration, NEM 3.0, comprises three distinct categories – domestic consumers (NEM Rakyat), commercial and industrial consumers (NOVA) and the government (NEM GoMEn) – and was initially intended to run from 2021 to 2023. It was extended once in Budget 2024 and again in Budget 2025. Recognising that increasing the use of intermittent sources will impact on electricity system stability, the budget mentions the development of a more holistic solar rooftop programme that accounts for local grid and network capacity.

Domestic and commercial-industrial quotas have seen encouraging uptake since the programme’s commencement, necessitating periodic increases over the years. The gradual rationalisation of electricity subsidies throughout 2023 and 2024 has likely incentivised high-consuming domestic users to lower their bills by installing rooftop solar. According to the Sustainable Energy Development Authority, only about 6% of the current quotas for NEM Rakyat and NOVA, 400MW and 1,100MW respectively, remain as of October 2024.

In contrast, the utilisation of the government’s quota remains poor with 41% of its original 100MW quota still available. This indicates that more can be done to unlock the untapped rooftop solar potential of government facilities nationwide, such as offices, hospitals, universities and schools. Nonetheless, Budget 2025 continues the government’s aspiration from the previous budget to model Putrajaya as a low-carbon city by installing solar panels on the roofs of car parks and 5km of pedestrian walkways.

Deployment of large-scale solar (LSS) infrastructure that is led by the private sector is also a crucial component of the government’s goal to achieve 70% renewable energy (RE) capacity by 2050. The fifth cycle of competitive bidding for solar – LSS5 – ran from April to July and the results are expected in December. Once online in 2026, these facilities will add 2,000MW to the grid, approximately doubling current solar capabilities. Aside from being the largest amount of solar capacity offered for bid thus far, LSS5 is also notable for having a separate floating solarcategory to moderate land-use constraints for traditional ground-mounted systems. This also opens avenues for other diversified approaches, such as the agrivoltaics concept mentioned in Budget 2025, which seeks to combine solar energy production with agricultural activities.

A synergistic application of multiple low-carbon technologies is evident in the ongoing Kenyir Hydro-Floating Solar Farm project highlighted in the budget speech. A collaboration between TNB and Petronas, half of the energy produced by this 1,000MW facility will be channelled towards a green hydrogen hub in Terengganu. Other state-specific initiatives include the establishment of RE economic clusters in Perlis and Sabah but details are not available yet.

The pivotal role of the electrical grid in enabling the energy transition cannot be overstated. NETR estimates that at least RM20 billion will be needed up to 2029 to ensure system resilience and stability. While the budget itself does not allocate specific funds for this purpose, it underscores that TNB and UEM Lestra will invest RM16 billion for transmission and distribution networks as well as to decarbonise industrial parks. The Corporate Renewable Energy Supply Scheme (CRESS) announced in September is also a positive step in liberalising the grid, allowing corporate consumers to source their electricity directly from RE suppliers. However, concerns have been raised about the perceived high system access charges – 25 sen and 45 sen per kilowatt-hour for firm and non-firm electricity respectively. As solar energy is expected to make up a significant portion of third-party grid access, it is a missed opportunity that direct incentives to support the wider deployment of battery storage systems to firm up this intermittent source have not been provided in the budget.

The Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act (EECA) was passed in June and will come into force in 2025. In support of this, Budget 2025 provides RM70 million in e-rebates for the purchase of energy efficient appliances and equipment as well as RM24 million in financing facilities through the Conditional Energy Audit and Energy Management Grant programme. While EECA is a step in the right direction, there are opportunities to move the needle further as the energy efficiency (EE) ecosystem matures, such as incentives that are proportional to the actual reductions in energy consumption. One example is the Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) mechanism where EE programmes are funded upfront by the service provider which then is repaid via savings generated by the customer. While this has been mooted before in 2018, it is encouraging that Budget 2025 codifies this approach for all government agencies and expects to realise up to 10% savings in electricity bills.

Two-wheelers and buses are the focus of transport sector electrification in Budget 2025 but there are no new incentives for personal electric vehicles (EVs) or public charging facilities. Rebates of up to RM2,400 for the purchase of electric motorcycles by those with annual incomes below RM120,000, introduced last year, continue. However, the allocation of RM10 million for this scheme is half of Budget 2024’s. For mass transport, Prasarana is expected to receive 250 electric buses in stages beginning in 2025 but it is unclear if these are part of or in addition to the 150 announced in Budget 2024. There is mention of plans for locally assembled EVs priced below RM100,000 but public charging infrastructure remains a bottleneck to widespread adoption. As of October, PLANMalaysia’s Electric Vehicle Charging Network dashboard reports that the country has only achieved 32% of its goal to have 10,000 charging stations by 2025.

Budget 2025 outlines incentives that serve as a precursor to the tabling of a law on CCUS by year-end. CCUS activities, including downstream sectors of the value chain, may be eligible for investment tax allowances, income tax exemptions and access to blended financing. Despite its conceptual appeal among policymakers, the implementation of CCUS in Malaysia remains a polarising topic and potential economic gains must be weighed against concerns, such as the importation of foreign emissions, integrity of geological storage reservoirs and opportunity costs compared with other mitigation measures.

A carbon tax is slated to be introduced in 2026 for the iron and steel industries as well as the energy sector but the exact implementation remains to be seen. Possibilities range from a direct tax on emissions, such as in Singapore, to a cap-trade-tax hybrid like in Indonesia. Starting with iron and steel production will help dampen significant post-2020 increases in sectoral emissions and aligns with the willingness expressed by industry associations to consider carbon-pricing instruments to accelerate the adoption of low-carbon technologies. For the energy sector, however, implementation may not be straightforward due to the role of gas as a key component of electricity generation, diminishing returns from coal power plants resulting from commitments to phase them out by 2044, and petrol and diesel subsidies. With a clear implementation timeframe now in place, the spillover impacts on the cost of living and interaction with international trade conditions, such as the EU’s impending CBAM, must bemeticulously studied.

Disaster-risk management and climate adaptation

The RM13 billion allocation for disaster-risk management in Budget 2025 represents an increase, but the implementation largely mirrors previous efforts, emphasising reactive and compensatory measures rather than a holistic approach in reducing disaster and climate risks. Appendix D provides a detailed breakdown of these allocations. While there are some innovative measures to enhance disaster relief and aid such as insurance scheme, the broader, holistic approach needed is still lacking. This is despite recent policy shifts, such as the National Climate Change Policy 2.0., which emphasises a more strategic approach and risk-based planning to address the physical risks of climate change.

Disaster-management allocation on the flood-mitigation front remains a large sum, though there is a reduction compared with last year’s RM11.8 billion allocation. Instead, RM3 billion is set aside for 12 approved flood-mitigation projects following the completion of eight previous projects. While these measures are critical in addressing immediate flood issues, in the long term, the shifting climate patterns require a reassessment of flood-management strategies beyond the current methods, such as river widening and deepening. More weight should be put on a forward-thinking approach to flood governance. For instance, a stronger emphasis on integrated river-basin management and climate-sensitive land use planning is essential. It offers not only a more holistic solution that help to tackle the root causes of flooding and promote long-term resilience but also presents a strategic shift towards integrated and adaptive disaster-risk management that promote long-term resilience.

Much of the allocation for infrastructure maintenance and upgrade comprises of engineering-based measures rather than a more holistic and risk-based approach. The coming monsoon season, including erratic rainfall and weather patterns, and more frequent flash floods point to a sense of urgency. As such, a number of allocations were made for maintenance of roads and drainage systems, both within urban and non-urban areas – such as RM5.5 billion for the Malaysian Road Records Information System (MARRIS) to utilise on state roads, including maintenance for drainage systems; RM150 million for the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID) for cleaning of drains and dredging of rivers in affected cities; and RM1 billion to repair non-main roads, including roads damaged by flood. While post-disaster repair works and upgrades are required, it raises concerns that this will simply be a routine response. Relying on fixes after each disaster risks turning this into a cyclical practice where resources are used for reactive measures. Instead, it should also be utilised to invest in long- term and climate-proof infrastructures climate risks in spatial and infrastructure planning.

On a positive development, there are specific allocations for targeted approaches towards addressing geological hazards, particularly in high-risk areas. An RM251 million allocation was provided for slope repairs and mitigation programmes to reduce landslide risks across the nation, especially during the monsoon season. There is also dedicated funding of RM21 million to address soil slips in vulnerable areas of Kerian Laut in Perak, Kedah and Perlis. Corresponding to recent tragedies and to reduce the risk of sinkholes in Kuala Lumpur, RM10 million will be channelled to DBKL to carry out a geotechnical survey of the soil layer structure in Kuala Lumpur’s Golden Triangle, including utilities mapping to identify potential weak spots that could result in sinkholes. While pending further details, the study will hopefully facilitate a more holistic and risks-based approach in urban and infrastructure planning.

A higher allocation for disaster preparedness, response and aid to NADMA as well as foundations of GLCs and GLICs reflects an acknowledgment of the growing severity of climate impacts on vulnerable communities. In this budget, NADMA’s allocation increased by 49% from the previous year’s RM300 million to RM582 million with RM300 million earmarked for the year-end flooding. The enhanced budgeting could translate into implementation of a more robust early warning system, more effective community preparedness and faster mobilisation of assistance to affected households. These funds should provide the agencies with ready access to resources needed for both immediate emergency response and sustained recovery efforts, given that there was no mention of the National Disaster Aid Fund as in previous years. However, upon reflecting on the scale of losses recorded in 2023, the RM168.3 million allocated to damage to living quarters and RM100 million under the National Disaster Aid Fund that year seem insufficient. While an additional RM20 million in matching grants for GLC and GLIC foundations may increase capacity to aid flood victims, whether this will address the recurring economic strains on affected communities remains to be seen.

To safeguard the livelihoods of farmers, breeders and fishermen from natural disasters, the Madani government continue its lifeline support by stowing RM25 million into the Agricultural Disaster Fund. However, this represents a 50% reduction compared with 2024, which, despite being higher, was only able to compensate half of the losses incurred by farmers. The reduced budget raises greater concerns about whether the fund will be sufficient to protect local food production against the growing impacts of climate change. Given this cut, there is an urgent need for more proactive measures to enhance disaster-risk management in the agricultural sector to strengthen climate resilience and local food security.

When paired with these relief measures, Bank Negara’s initiatives, such as Skim Perlindungan Tenang and Disaster Relief Facility further cushion the impacts of disaster and offer overlapping assistance across the socio-economic spectrum. As part of the Skim Perlindungan Tenang, two million recipients of STR will be provided with a RM30 vouchers to help cover part of the cost for Perlindungan Tenang insurance products. This allows low-income groups access to basic protection against personal accidents but also to protect themselves against losses from disasters. Similarly, RM300 million has been set aside towards the Disaster Relief Facility to alleviate any financial burden faced by SMSEs affected by floods. The sum represents a modest increase from RM231 million in 2024. However, as of July 2023, only 53% of the funds had been disbursed. While these schemes reinforce financial protection, the low uptake suggests a need for increased public awareness and interest. To meet the full scope of disaster risks, further scaling and refinement of these programmes is necessary.

Overall, while Budget 2025 provides support for flood management and disaster relief, there is a palpable absence of measures to address other climate hazards that are expected to become more frequent and intense under a potential 2° C scenario. Aside from flooding and drought, hazards, such as heat waves and sea-level rise, underscore the need for holistic adaptation measures. The Mid-Term Review of the 12MP outlines initiatives under Malaysia’s National Adaptation Plan (currently in development), such as nature-based solutions, heat action plans and early warning systems, to enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities, hence showcasing the groundwork in place. While the National Disaster Risk Reduction Policy 2030, published earlier in October, aims to integrate strategic disaster-risk reduction into all sectors. Given proper implementation, these policies will provide clearer guidance on addressing emerging threats, ensuring resources are allocated for a broader range of disaster risks. Ultimately, this points to the need for risk-based planning within national development and a shift from a predominantly mitigation-focused approach in disaster- risk reduction, which will not suffice in the long term given the growth of both the Malaysian economy, society and climate impacts.

Appendix A

Non-exhaustive list of industrial development initiatives announced under Budget 2025, and their corresponding fiscal allocations if applicable.

Appendix B

Allocation for natural resource and environmental management under Budget 2025

Appendix C

Allocations for energy transition and low carbon development

Appendix D

Allocations for disaster-risk management under Budget 2025