Integrated health and social services could transform elderly population’s final years

By Yvonne Tan and Lee Min Hui, UNFPA Malaysia

As Malaysians grow older, the country’s collective health and social care needs are set to surge exponentially. But is Malaysia prepared for a rapidly ageing nation and the corresponding strains it will pose to its healthcare and social care systems?

What with the country’s public health and social care systems operated and governed separately, navigating what appears to be entirely disconnected systems may prove challenging for the average elderly Malaysian to access. The lack of an integrated care system may mean that Malaysia is woefully unprepared to support the weight of a rapidly ageing society.

While Malaysians are living longer, they are not necessarily living in better health. At least 9.5 yearsare spent in poor health in 2019, an increase from 9.1 in 1990. The average increases to 10.5 years for women – indicating that there is a gendered dimension to ageing. As a whole, the disease burden faced by older Malaysians is significant, with 41% prevalence of multimorbidity, managing two or more NCDs. As a result, health complications make ageing needs more complex.

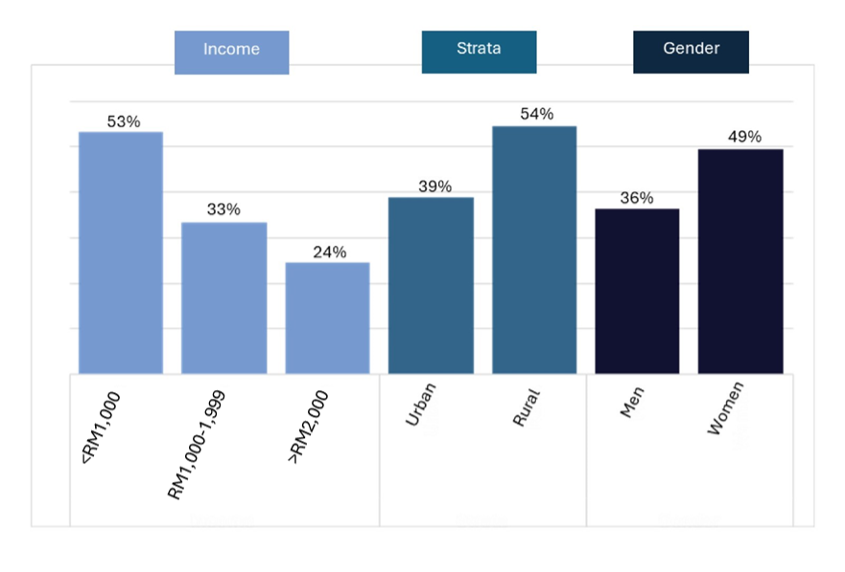

But older persons also require social care support in everyday life, especially what is termed “instrumental activities of daily living” (IADLs). Their dependency hinges on key factors like income, strata and gender.

The 2018 National Health and Morbidity Survey reported those with lower incomes had higher dependency in terms of IADLs. Similarly, people living in rural areas reported greater dependency compared to urban residents, as well as for women compared to men (Fig. 1). This means that social care needs will be most dire for those most vulnerable and least able to access formal services.

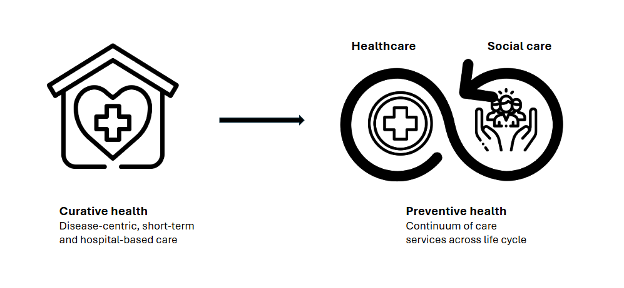

This situation of growing health and social care needs is worsened by the fact that both public health and social care systems are run as entirely separate domains. Like most countries, Malaysia’s public healthcare system is focused on disease-centric, short-term and hospital-based care.

Meanwhile, its social care systems, which falls under the country’s social welfare system, have historically been underinvested in and has especially poor coverage of public social care. Private care options, on the other hand, are more numerous but accessible only to those who can afford them.

Coordination challenges

Coordination across the two is commonly left to the consumers of such services to navigate. But with elderly care often requiring multiple providers and frequent transitions between care settings, transitioning between entirely separate systems could disrupt the continuity of care which can contribute to more negative health outcomes. Put together, more older Malaysians are going to require health and social care services at a volume that the country is unprepared to provide.

An integrated care system will offer not only seamless provision of services for elderly as they transition across care settings, but also ease the burden of informal caregivers and care recipients who must navigate these separate systems.

According to the World Health Organisation, integrated care is a means of providing tailored or personalised forms of care that enhance the physical and mental capacities of older persons while supporting independent living in their own homes. It is a move away from curative or medicalised care paradigms centred around treating individual diseases or conditions.

Evidence suggests that integrated care services can reduce unnecessary hospitalisations, thereby alleviating the strain on our public hospital system while also improving quality of life.

For example, an elderly person who has just undergone medical surgery and in need of rehabilitation services can benefit from an integrated care system that identifies what treatments are necessary and where to receive it. An integrated care system is not a novel idea, but it could be transformative for elderly Malaysians if implemented well.

Research shows that integrated care is most effective when rooted within community settings. This model has the capacity to deliver care services directly to where individuals live, making it a more cost-effective alternative to residential care.

This approach can include a wide range of care configurations that is more flexible, such as daycare and home-based care. Further, a community-based approach aligns with Malaysians’ preference for ageing-in-place, where older adults remain in their own homes and communities. In fact, the MARS survey reported high levels of readiness for home-help services over full-time residential facilities. Overall, it can support older persons in maintaining independence, meet their needs and preserve social connections.

Towards integrated care system

To do so, Malaysia needs to make major systemic changes to integrate both its health and social care systems. Efforts in other countries towards community-based integrated care services for older persons may be important points of reference for implementation, Japan, for example, has established a structure called Integrated Community Care Support (ICCS) Centre that aims to offer support for medical care, long-term care, preventive care, and support for daily living and housing within a 30-minute walk radius to residents.

In Malaysia, pilot efforts have already been made in Sarawak: the Geriatrik Komuniti-Integrated Service Delivery (GeKo-ISD) is implemented across 32 primary healthcare centres leverages on public primary healthcare clinics to identify patients’ care needs and connects them to relevant services. The programme contributed to the reduction of frailty scores by 19% within three months. This framework may provide an opportunity for Malaysia to begin piloting integrated care on a wider scale.

To establish an integrated care system for older persons, fragmentation in governance needs to be addressed urgently. Presently, Malaysia’s policies on older persons are guided by the National Policy for Older Persons in 2011 and National Health Policy for Older Persons in 2008.

But what they also reveal is a disjointed framework involving different government bodies. The health-related aspects of aged care fall under the Ministry of Health (KKM), while social care services are managed by the Department of Social Welfare (JKM) under the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (KPWKM).

Improved interministerial coordination between KKM and KPWKM is essential for facilitating the development of a comprehensive integrated care system, without which it would be difficult to ensure seamless service delivery and meet the diverse needs of older adults effectively.

Systemic changes to the country’s public health and social care systems – both in terms of governance and delivery of services – are one of the most effective ways that Malaysia can effectively support its ageing population.

The next step would be to make those services more widely available, accessible and high quality. Overall, such a move could serve to be an essential form of social protection for a rapidly greying population, the majority of whom currently lack adequate savings for retirement. To get there, Malaysia needs to make decisive preparations now before it is too late.