Kieran Li Nair was quoted in The Edge Malaysia, 30 December 2024

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 30, 2024 – January 12, 2025

Minister of Economy Rafizi Ramli has been promoting a new bill on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) since May. The ministry says its implementation is important to Malaysia’s decarbonisation efforts.

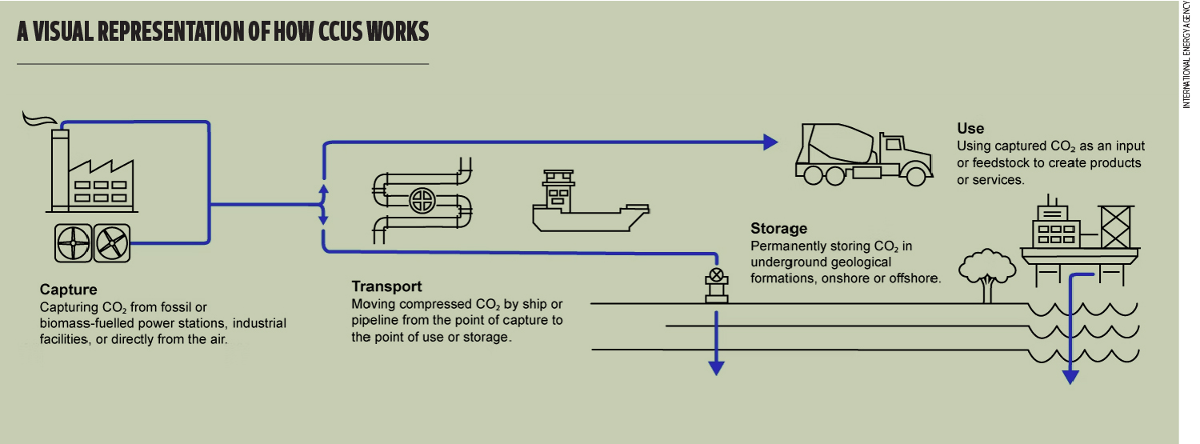

The CCUS bill, originally aimed to be tabled in November, will regulate the capture, transportation, utilisation and permanent storage of greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide (CO2), either within Malaysia or imported from other countries. CCUS is recognised as one of six decarbonisation levers under the National Energy Transition Roadmap.

The bill will be able to help high-emitting sectors where carbon reduction is difficult, such as oil and gas, steel and cement.

Rafizi says once passed into law, it will bring about significant potential for economic growth.

While CCUS has received considerable attention, critics have raised questions over its risks and how it should be governed. ESG delves deeper into these issues.

Is CCUS needed for Malaysia’s net zero goals?

When it comes to carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), experts say the fact that transitioning to a low-carbon economy is not as straightforward as replacing an energy source. Weather-dependent sources of electricity such as solar and wind are not as stable as coal, and there will be emissions that are impossible to abate.

“To achieve its long-term emissions targets, Malaysia needs to diversify its technology options, while also implementing energy-efficiency measures and scaling up nature-based solutions,” says Dhana Raj Markandu, senior analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (Isis) Malaysia.

Dhana sees the CCUS bill as paving the way for a framework to explore this technology in a more controlled and transparent manner. This view is shared by his colleague, Kieran Li Nair, senior researcher at Isis Malaysia.

“As [Malaysia is] an oil-producing nation reliant on hard-to-abate industries, CCUS can play a role in assisting these industries to reach their decarbonisation goals while exercising all other existing transition options, so long as an adequate balance is struck,” says Kieran.

However, the aggressive promotion of the CCUS bill has raised concerns among some parties. They worry that the bill is focused more on CCUS’ commercialisation and economic growth potential rather than its environmental benefits, leading to it being rushed without sufficient protection for the environment.

“There is concern that the main purpose of the bill and development of CCUS is based on developing carbon capture as an industry rather than emissions abatement,” she adds.

Kieran says the aggressive promotion of CCUS and the bill’s rushed timeline compared with that of the climate change bill also raises questions.

“[This opens Malaysia to risks such as] an overreliance on nascent technologies for decarbonisation, inadequate safeguards for issues such as leakage and stranded assets, issues surrounding transboundary storage, capacity and technical expertise being engaged to implement these measures, and environmental and social challenges,” she explains.

This is a sentiment shared by Pushpan Murugiah, CEO of the Centre to Combat Corruption and Cronyism (C4), who fears not enough consideration was given to the environmental impacts.

“The whole draft didn’t take into account key elements like environmental issues, sustainability of indigenous rights and land issues, so we felt that a lot of the framework is not complete,” says Pushpan.

C4 was one of the consultants involved in the initial discussions when the bill was first put forward, but further discussions have not been held, and Pushpan is concerned that if the bill is passed without speaking to the relevant stakeholders and experts, potential long-term problems would not be taken into account.

Despite government assurance that CCUS technology is proven and viable, citing the example of Norway permanently storing more than 20 million tonnes of CO2 since 1996, Pushpan notes that technological efficacies are still low, meaning the rate of effectiveness is less than 70%.

“In the long term, if we have that kind of storage here, the concern is [for] people who are living around that storage area, the rights of those people. And what if there is [a leak where the carbon emissions] come back up again? How do we manage that?”

C4 does not consider CCUS as something worth fully investing in and sees it as more of a false solution.

Isis’ Kieran is more open to the idea.

“There exists a role for carbon dioxide removal technologies such as CCUS to play, particularly for hard-to-abate and heavy industries. However, as it stands, the risks of CCUS outweigh the benefits, and more precaution must be taken in Malaysia in carving out CCUS as an industry,” she says.

According to the Sarawak Land Rules 2022 on carbon storage, financial penalties can be imposed by the government if greenhouse gases escape from a reservoir, but no minimum amounts are specified.

“Unlike carbon credits, there is no independent third-party verification and the penalties for failure are unclear. Such regulatory gaps should be addressed before large-scale carbon storage starts,” Kieran stresses.

Are businesses ready for CCUS?

Much of the conversation surrounding carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) tends to focus on the oil and gas (O&G) industries, with Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) already deep into its carbon capture and storage (CCS) plans, having signed a land rental agreement with Kuantan Port Consortium for its Southern CCS hub in Pahang.

Despite this, there are concerns from other high-greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting industries where CCS technology is not as developed.

According to the Cement & Concrete Association of Malaysia (C&CA), while CCS presents new possibilities, the technology is not yet viable and the industry is currently focused on immediate decarbonisation actions.

“CCS is an emerging option for the cement industry, with several trials underway, primarily in Europe and the US, supported by government grants. However, achieving operational scale remains a goal for the future,” says C&CA in an email response.

C&CA described the implementation of CCS technology as a significant endeavour similar to constructing additional infrastructure around existing facilities. This requires significant investments in the plant and renewable energy to power the operation, in addition to the required development of infrastructure for the transportation and storage of CO2.

“Implementing CCS would involve additional costs, estimated to be more than double of cement production cost alone based on current estimates. This will impact housing and infrastructure costs” C&CA notes, emphasising the importance of considering economic impacts carefully.

C&CA notes that while CCS offers potential and is open to embracing the technology once it becomes viable, current decarbonisation actions should be prioritised.

To meet this, C&CA notes the need for several key support measures from the government such as mandating low-carbon materials, grants and assistance for technology transfer, lifting restrictions on ground-mounted solar systems and promoting the adoption of lower-carbon alternative fuels.

C&CA says these measures would ramp up carbon reduction efforts in the industry, and when CCS becomes fully viable, it should be implemented in addition to these measures.

How can CCUS be financed?

With the high cost of entry, banks play a pivotal role in driving carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) commercialisation. They connect investors, clients and sponsors, while de-risking projects through subsidies, guarantees, blended finance and public-private partnerships.

According to Shahril Azuar Jimin, group chief sustainability officer at Malayan Banking Bhd (Maybank), the bank is already well-positioned to mobilise financing for qualified CCUS projects, leveraging its Asean network, expertise and its Transition Finance Framework to support the CCUS value chain and development.

Adopting CCUS technologies requires significant upfront investment. Therefore, Shahril suggests a shared infrastructure hub that can reduce these costs through economies of scale.

“The planned three CCUS hubs by 2030 have the potential to boost investor confidence and attract foreign and domestic direct investments. Meanwhile, carbon pricing, such as Malaysia’s 2025 carbon tax, incentivises cleaner technologies like CCUS by internalising environmental costs,” says Shahril.

As of now, the CCUS industry presents challenges for non-recourse project financing, as the credit analyst community needs to fully understand the credit risks of such projects. Thus, most financing for CCUS projects comes from equity investments, and government or supranational funding.

“Nevertheless, the growing pipeline of 20+ regional CCUS projects, including the Petronas Kasawari CCS [project] and Balikpapan Refinery, will accelerate bankability by driving economies of scale, establishing track records and building stakeholder confidence,” says Shahril.

He adds that Maybank is optimistic about CCUS developments and is preparing to provide end-to-end solutions for its adopters. This includes facilitating financing, advisory, insurance and partnership opportunities to enable a robust CCUS ecosystem in the region, while supporting small and medium enterprises or vendors who will form part of the supply chain.

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia, 30 December 2024