Zero-cost model one way to protect migrant workers forced to fork out exorbitant fees

By Yvonne Tan

The National Action Plan on Forced Labour (NAPFL) 2021-2025 is Malaysia’s first comprehensive plan aimed at eradicating forced labour by 2030 and promoting safe migration practices.

The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) imposed a ban on imports from Malaysia’s Top Glove Corp in 2020 and following the US State Department’s Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report ranking the country in tier three, the lowest tier, for six consecutive years until 2022. It is a position shared with the worst countries for human trafficking in the world, including North Korea and Afghanistan.

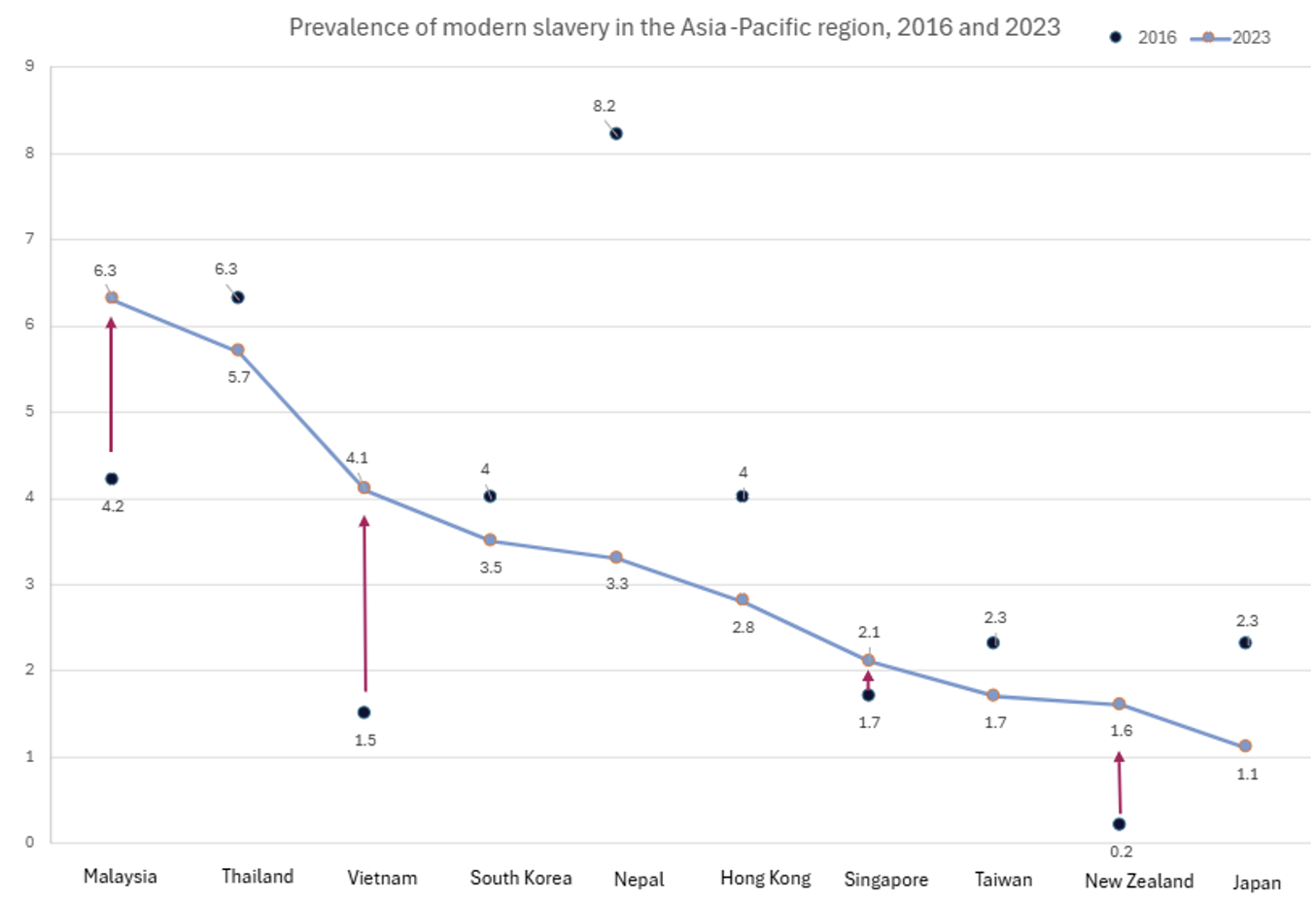

One of NAPFL’s key goals is to strengthen migration management and recruitment practices by 2025, improving regulation of recruitment agencies and setting time-bound targets to reduce forced labour in supply chains. However, even as the plan nears its end, progress on this front has been limited. Indeed, by some measures, the problem has worsened. In 2023, the Global Slavery Index suggests that 6.3 out of 1,000 people are affected by modern slavery in Malaysia – up from 4.2 per 1,000 in 2016 and ranking 12th highest in the Asia-Pacific region, above regional neighbours Thailand and Vietnam.

Addressing root cause of forced labour

An explanation for this lack of progress is the failure to address the root cause of the problem: Malaysia’s migration model itself.

Under the current model, migrant workers often must bear exorbitant fees charged by private recruitment agencies and intermediaries. These high recruitment fees often plunge migrant workers into debt bondage, placing them in a cycle of debt and dependency that makes them vulnerable to exploitation. In other words, the current model may place migrant workers at risk of forced labour even before they step foot in Malaysia.

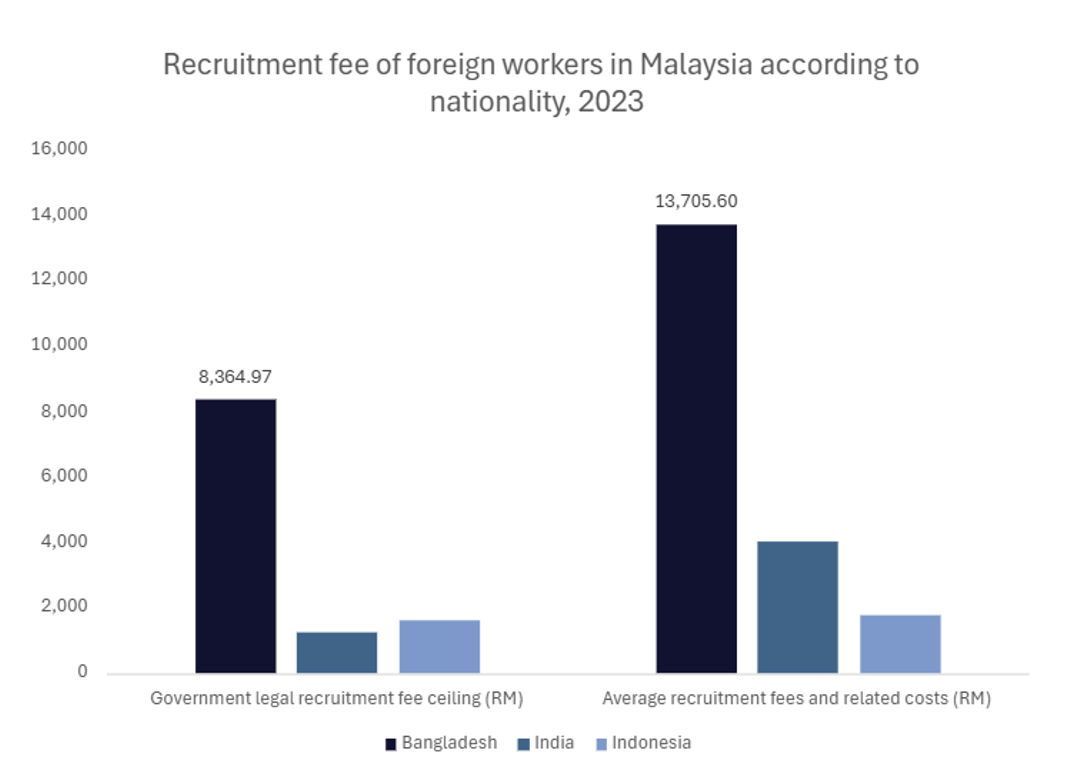

For instance, a Bangladeshi migrant worker in Malaysia could take 10 months of minimum-wage earnings just to repay these recruitment costs. Meanwhile, some 38% of migrant workers in oil palm plantations needed to take out to loans just to pay the hefty recruitment costs that are typically almost double the government-mandated legal recruitment fee ceiling. That is to say nothing of the further wage deductions employers takes for accommodation, electricity, groceries and water bills, ranging around RM400 per month.

These are not hypothetical examples. Several high-profile cases highlight the severity of forced labour in Malaysia, illustrating the consequences of a flawed migrant worker management system. Eight migrant workers were coerced into working as forced labourers in Lojing Highlands, Gua Musang, for up to seven months. Likewise, wage disputes continue to surface, such as RM 1,035,557.50 in back wages to 733 migrant workers legally brought to work in Pangerang, Johor but not provided with employment. Furthermore, a local contractor supplying components to major Japanese electronics firms has failed to pay more than 200 of their foreign workers since April 2023.

This exploitative model persists because forced labour is immensely lucrative. Recruitment agencies, intermediaries and companies stand to benefit from high recruitments fees and suppressed wages at the expense of workers.

Globally, forced labour in the private economy generates US$236 billion (RM1.02 trillion) in illegal profits per year, estimated at almost US$10,000 (RM 42,850) profit per victim from recruitment fees and wage underpayment. The flipside is the large opportunity cost of reducing forced labour. Estimates suggest that bringing these workers into formal employment with adequate social protections would unlock about US$611 billion (RM 2.61 trillion) in additional GDP.

Towards zero-cost migration model

While there is no single solution to tackle the large and multifaceted issue of forced labour, scaling up a zero-cost migration model for migrant workers of all nationalities would strike at its financial root.

First implemented by the Malaysian government in 2018 for Nepali workers, a zero-cost migration model puts the onus on employers who want to hire migrant workers to pay for them. The same was adopted, in principle, for domestic workers from Indonesia and the Philippines. This way, it is employers, not workers, who should cover the medical, insurance, equipment, travel, lodging and other associated expenses related to recruitment. This would also be in alignment with ILO Convention No. 181, which prohibits charging recruitment fees to workers as these costs should be paid by the employers or subsidised through government-to-government arrangements. By eliminating the significant upfront costs on workers, this model helps prevent them from falling into debt bondage, a common precursor to forced labour.

Evidence supports the effectiveness of this model. A 2018 impact study on the Nepal-Jordan corridorcompared conventionally recruited workers with fairly recruited workers under zero-cost schemes. The study showed that the latter exhibited higher productivity and were also more likely to have a more positive experience with their supervisors and managers. Put simply, a zero-cost migration model balances the interests of migrant workers, employers and host-country nationals – protecting the rights of workers while ensuring firms can access the labour they need.

Many economies have already transitioned to such a model. Taiwan has successfully implemented models where employers cover all recruitment costs, including processing, travel and other fees, rather than passing these costs onto migrant workers. Hong Kong allows recruitment fees for domestic workers to be capped at no more than 10% of their first month’s salary, while in Singapore, licensed intermediaries to charge no more than one month of a worker’s fixed salary for each year of employment, with a cap of two months. Thailand has also adopted the principle of zero-fee principle for migrant workers and offers competitive wages, making it a more financially attractive destination compared to Malaysia.

Of course, in practice, such a model would require careful implementation and monitoring. Legitimate concerns exist that unscrupulous employers might circumvent these models through “kickback bribes” from intermediaries or by offsetting recruitment costs through reduced wages, fewer benefits, or increased working hours – essentially perpetuating migrant worker exploitation through different means.

To address these vulnerabilities, implementing robust monitoring and regulatory framework is essential to ensure transparency and effectiveness. This includes labour inspectors empowered to audit recruitment practices throughout supply chains along with recruitment-related offences. Equally important are effective, accessible grievance mechanisms that allow workers to report forced labour conditions and seek justice without fear of retaliation.

Malaysia’s struggle to eliminate forced labour cannot be fully resolved through surface-level reforms alone. It requires addressing the root cause: a migration system that financially exploits vulnerable workers before they even begin employment.

To this end, a comprehensive zero-cost migration model offers the most promising path forward. Not only would this approach honour Malaysia’s international commitments and improve its global standing, but also strengthen the country’s economy and labour markets through increased productivity and reduced exploitation. After all, truly ending forced labour will mean taking aim at systems that profit from human exploitation.

This article first appeared in The Interpreter, published by the Lowy Institute.